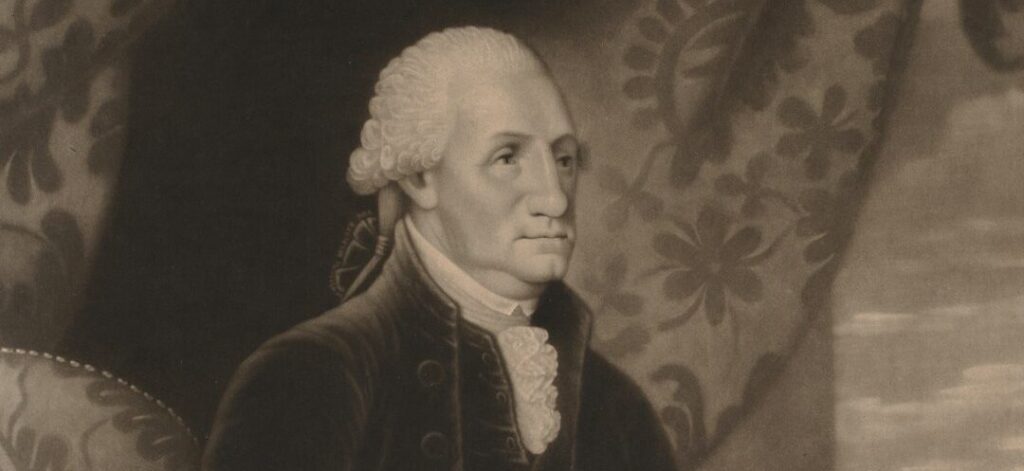

George Washington is said to have one day quipped: ‘If a man does not believe in God, he should be locked up’. Whatever the actual beliefs of this founding father of the United States of America, the phrase gives food for thought. It’s simple enough to understand: if a man does not believe in God, he is not likely to have any moral code outside of his own judgment, and if he is his own subjective moral code, how can you trust him? He is potentially capable of the worst crimes. So better put him behind bars.

An objector might contend that most criminals historically did actually believe in God, but such belief did not prevent them from committing their crimes. So what’s the point? The point is that, even though people often act contrary to their beliefs in relatively small matters, religious beliefs will help keep people out of serious trouble, or if they fall into it, will eventually help them turn their life around, whereas persons with no beliefs easily become the perpetrators of further crimes. Why? Because in their mind there is no ultimate tribunal – if human justice can be avoided, it’s clear sailing for whatever you can get away with. Indeed, history has given us some particularly frightening examples of men who avoided human justice because they were at the top of a system that answered only to themselves. Professed atheists, men like Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong, were responsible for the deaths of millions of people because they were convinced that this world is all there is, that they could make earth into a paradise of their liking and that they would answer to no one for their actions in a future life.

The Washington jest came to me as I set out to pen this article. Last month I pointed out that the tripartite principle of lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi is actually of a single piece. Our manner of prayer, our creed and our moral code are interconnected. If one is faulty, the others are sure to follow down the drain. To outline a way of making our way back to the soundness of Tradition, it appears to be of the essence to understand where we went off track in the first place and thus propose a coherent explanation for the situation we find ourselves in. We have taken some wrong turns and are going in the wrong direction. Identifying actual moments or events that signalled a change of orientation is essential to assessing the risks of our present predicament. For today we shall concentrate on a point of the lex credendi that was, for all intents and purposes, brushed aside, opening a broad, deviant path that has led to accelerated corruption of the lex vivendi.

Washington Was Right

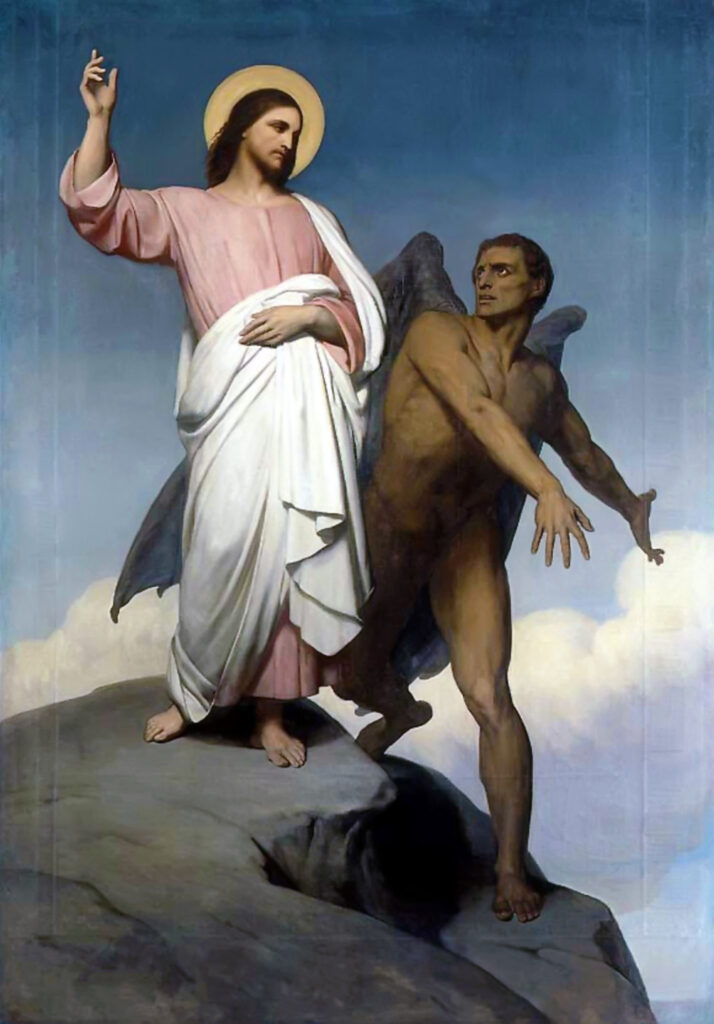

I mean to speak of Hell. Not of ‘hell’, but of Hell. Plenty of people still speak of ‘hell’. We often hear of the ‘hell’ of Auschwitz or the ‘hell’ of the Gulag or the ‘hell’ of the trenches in World War I. Psychologists speak readily of the ‘hell’ of certain severe mental traumas, or the ‘hell’ of child abuse, etc. In any of these ‘hells’ and many others, a person suffers intense trauma that marks them for life. Some may have undergone torture that has left not only their mind but also their body, deeply and irremediably wounded. On the other hand, the persons who survive these traumas do so thanks to the help of loving family, friends or professional medical staff. More importantly, if they are persons of faith, they can often go through them without losing the conviction that it will soon end and that God will prevail; love will conquer hate. All these ‘hells’ are real; we would wish them on no one. These, however, are not my topic.

I refer to Hell, which is the state (and the place) of eternal damnation, where damned angels (demons) and damned human souls are forever separated from God, suffering torments with which the worst of our earthly ‘hells’ can only be faintly, if at all, compared. In Hell, there is no family; there are no friends; there is no one at all, for Hell, even though densely populated, is absolute solitude; indeed, even though there are many demons and damned souls, they hate each other – there is no communion in Hell. The worst thing about Hell, however, is that God has been definitively rejected, and there will never be another chance, ever, to go to Him or to see Him. When we consider that each human has deep in their soul a scintilla animae, a divine spark as it were, constantly drawing them to God and that this loving God has been lost forever through their own fault, we come to the edge of a precipice that we do not readily want to look into. But we must.[1]

Some will object: Such a Hell could not possibly exist, because God is good. Regarding the existence of an everlasting Hell, leaving aside the New Testament’s multiple references to it and its clear and oft-repeated place in the Church’s Magisterium, one would be hard-pressed to find any religion in the true sense of the term that does not believe in a state of definitive punishment. All men in every culture and religion have always held that there are paths of evil from which there is no return. If there is not, that can only mean there is no ultimate censure for evil and, for all practical purposes, no God. Washington was right – men need a definitive deterrent from the deviant impulses of their nature.

It will be news to no one that over the last century or so, there has been a growing refusal to acknowledge a state of ‘no redemption possible’. Interestingly, some liberal Protestant theologians imperceptibly returned to the Catholic doctrine of Purgatory when they started positing that unending punishment was simply irreconcilable with the infinite goodness of God. In this way, without adopting the terminology of Purgatory, they have for all intents and purposes, retrieved the notion. On the Catholic side, given the clear definitions of the Church, it was not possible to deny the existence of an everlasting Hell without officially being labelled a heretic. Another path was taken by numerous theologians, and it can be summarised this way: ‘Yes, Hell exists, but we have every reason to believe it is empty.’ In other words, God created it as a man would create a ghost to spook children away from certain forms of behaviour.

These theologians forget something. To say, ‘Hell does not exist’ and to say, ‘Hell is empty’ lead to the very same conclusion. In either case, Jesus Christ reveals Himself to be, not just a false guide, but worse, a pathological liar. The reason is obvious for anyone who has actually read the Four Gospels and the Epistles: Jesus and the apostles frequently refer to the reality of eternal damnation. They clearly speak, on multiple occasions of eternal damnation, not as something that might possibly happen, but that will happen for unrepentant sinners, something that is happening as we speak for those who have already rejected God and died in that state. Now Jesus, as Son of God, knew what He was talking about, so if He told us something that He knew to be false, He was lying. And if He was lying, why would we want anything to do with Him? As C. S. Lewis brilliantly put it (albeit arguing from a different perspective): ‘He has not left that option open to us.’[2]

Words Don’t Lie

This was the reasoning of every Christian generation, from the days of the Apostles to ours. An incident at the Second Vatican Council will show how true this is. When a number of the Council Fathers asked that the dogmatic constitution Lumen Gentium state explicitly that there will actually be people who are damned forever in Hell, the theological commission charged with amending the text answered that such was not necessary. Reason? The text already cites the Gospel which expresses itself, not in the grammatical conditional, but in the grammatical future; in plain English, this means that Jesus is speaking not of something that might happen, but of something that will happen. In other words, Jesus was not speaking as a hopeful preacher wishing to deter people from doing things that could lead them to an awful outcome, one that He hopes to prevent. He was, on the contrary, speaking as a prophet in the strict sense of the term, that is to say, as one who sees the future and announces what will certainly come to pass.[3]

One sometimes hears: That’s all nice and fine for the God of the Old Testament, a ‘god of fire and brimstone’ who sent entire peoples to Hell; but the God of the New Testament is so kind and merciful that He welcomes all into Heaven. Or this: The God of the Old Testament was all just, whereas the God of the New Testament is all mercy. A first response would be to point out that the word ‘mercy’ occurs no less than 261 times in the Old Testament, and that the very last book of the New Testament, and therefore the one that we would think benefited the most from the ‘God of the New Testament’, is the one that tells us with a triple repetition of the ‘lake of fire and brimstone, the second death’ into which shall be cast such people as ‘the cowardly, the unbelieving, the vile, murderers, the sexually immoral, those who practice magic arts, idolaters and all liars’ (Cf. Apoc 14:10; 20:9; 21:8).

A second and more substantial response would be that the eschatology of the Old Testament is incomplete. The Hebrews had been given no clear idea about the afterlife. One died and went to Sheol, the Netherworld, where one joined the ranks of the shadows of one’s ancestors, waiting for the coming of Messiah. In the deuterocanonical books, however, written in Greek in the centuries immediately before the birth of Christ, it becomes clear that the souls of the just are rewarded after death, and that the souls of the evil are punished (cf., for example, Wisdom, 2 and 3, and 2 Macc 7). And yet, the exact nature of the rewards and punishments of souls in eternity would not be fully revealed until the coming of Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself. It is to Him that the crystal-clear teaching of the Catholic Church on what happens after death owes everything. He is the one who taught us, by Himself or through His apostles, that the just are destined to see God face to face (cf. Mt 5:8; 1 Jn 3:2), while unrepentant sinners will burn forever in everlasting fire, cursed by God and separated from Him in outer darkness and gnashing of teeth. All will recover their bodies at the end of time so that the whole human person, body and soul, will either enjoy life with God or suffer excruciating pain far from His Face.[4]

This is what, not only Catholics, but virtually all Christians believed until roughly the middle of the 20th century. At that time, theologians made some ‘discoveries’ that had apparently remained hidden from Jesus, the Apostles, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, the Ecumenical Councils, the official catechisms and all the saints who spoke or wrote about the matter. The first ‘discovery’ was that human nature is already in the supernatural realm, and so if you are a human, you are already on the way to God, you are an ‘anonymous Christian’, and so unless you commit some awful unforgivable crime such as genocide and refuse to repent, you are going to Heaven. A simple way of putting it is that humans are ‘programmed’ to go to God, and so unless they really go out of their way, they will be saved. It’s what has been called the ‘supernatural existential’.

The second ‘discovery’ was that we had not at all understood the meaning of the glorious descent of Christ into Hell after His death.[5] In fact, contrary to what the Church has always taught, it was ‘discovered’ that when Jesus ‘descended into Hell’ as we say in the Apostles’ Creed, He did not appear in glory to the just souls of the Old Covenant, but actually suffered the pain of damnation. He became the only human being to be ‘damned’ by God His Father and He thus atoned for damnation, thereby making it virtually impossible for any others to be damned in Hell. Even if they are, they will be ‘fished out’ of Hell by the omnipotent mercy of God (including the demons, and in this a connection was established with the apokatastasis of Origen, several times condemned by the Church in the early centuries). This gave rise to the conviction that we must ‘dare hope that all be saved’, the well-known title of a widely read, but profoundly unconvincing, book. To summarise, virtually everyone is on the way to salvation without knowing it and even without wanting it, but even those who might be damned for awful crimes will eventually be saved as well along with all the demons.[6]

The Key to a Very Unpastoral Approach

Since roughly 1950, almost all priests have been taught these two ideas in different forms, taken virtually on faith, without wondering how it is that for the first two millennia of its history, the Church was unaware of them. What the clergy retained, and what they came to preach, is the foregone conclusion: everyone is saved. All this was facilitated by what I referred to last month as the ‘spirit of Vatican II’. There was change in the air, and even if the Council didn’t say so – it actually said the opposite, as the quoted text from Lumen Gentium makes clear –, it felt good to assume everyone is saved, for that meant that now we could dialogue with the world without worrying about teaching them things that are unpleasant to hear and that they don’t really need to know in the end. After all, so they say, God is ‘nice’.

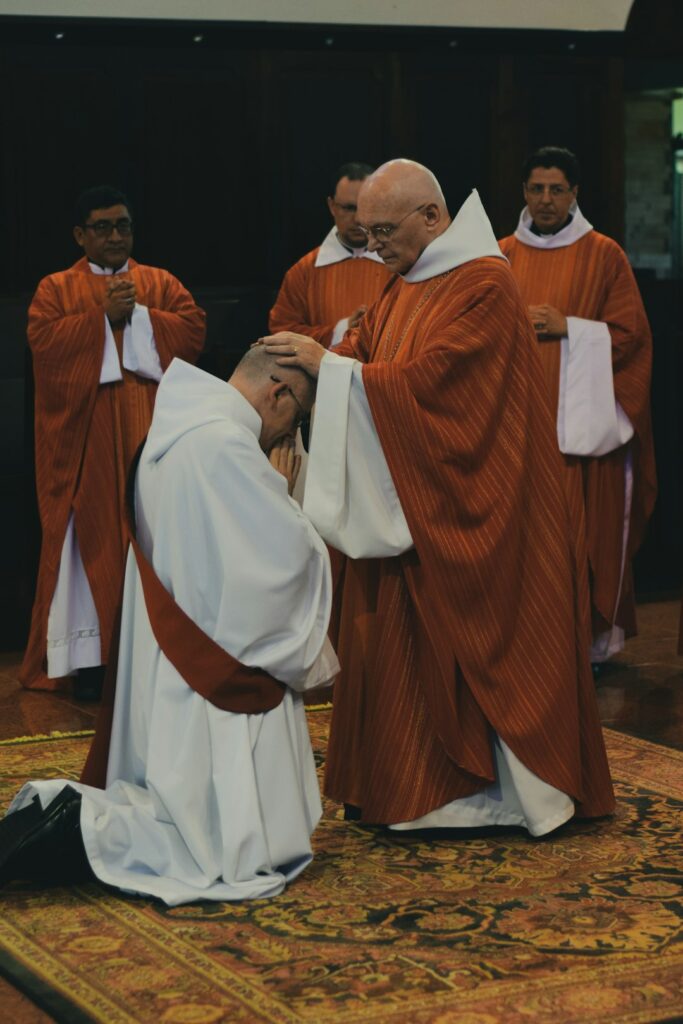

It need not be insisted upon that this conclusion has literally turned the pastoral approach of the Church on its head. Before this, every priest knew that people committed sins that led them to Hell, and it was his job to preach conversion and to forgive sins through the sacraments of Baptism and Penance so that they would be converted and not be lost. This was a justification for the great sacrifice of giving up a potential wife and family, and many other things as well. It was worth it. It was a tremendous ‘call to exertion’ that gave incentive to their vocation. Once, however, it was being widely taught that we had gotten this all wrong, that in the end ‘everyone goes to Heaven’, the pastoral approach inevitably took other forms. And so, the task of the average priest now consists of working for the peaceful coexistence of peoples, for the rights of minorities, for protecting the environment, and above all coordinating all the other pastoral workers, etc. Mind you, these things, when properly understood, are not foreign to the Church’s mission. The priest’s essential work, however, is elsewhere. It is in preaching the kerygma, that is,the truth of salvation and the need for repentance, and in bringing that salvation through the sacraments. That’s why the priest exists; this is the reason he is ordained: to save souls, one by one, performing duties that only he can, thanks to the indelible priestly character he received in sacred ordination.

But the new pastoral approach also had another grave outcome. The blackout on eternity and the virtual disappearance of Hell from the preaching of the Church had a disastrous effect on the general breakdown in morals. Moral decadence has been a recurring problem in every age, yet in times of crisis, former generations had a mighty leverage in the Church’s vigorous preaching of the Last Things. Her priests knew how to menace souls with Hellfire, and they did so with much success. But if we now ‘know’ all are saved, why make people uncomfortable and ask them to change their lives? Today, the clergy for the most part seem to make it a moral duty to reassure sinners (and themselves!) that God loves them in spite of their sins and will save them no matter what, forgetting that it is precisely the abuse of God’s love that makes sin so serious. The salvation of souls cost God His Blood – Grace is not cheap.

Some may object that we shouldn’t threaten people with Hellfire, but just encourage them to love their neighbour. The second of the great commandments remains an essential component of catechetical formation, but it is not sufficient, for a number of reasons. The first reason is that the Lord Himself and His Apostles acted otherwise, speaking frequently of the serious reality of damnation. The second reason was marvellously summarised by St Ignatius of Loyola in his meditation on Hell, when he instructs the retreatant to ‘beg for a deep sense of the pain which the lost suffer, that if because of my faults I forget the love of the eternal Lord, at least the fear of these punishments will keep me from falling into sin’.[7] Which of us can pretend to have so much love for God that sin holds no attraction for us? The answer to that question was already given by St John: ‘If we say that we have not sinned, we make him a liar, and His word is not in us’ (1 Jn 1:10).

Some years ago, Cardinal Robert Sarah wrote an admirable book with the provocative title God or Nothing. The title itself tells us that unless God is real in our lives, nothing else can make up for His absence, and the world can only end up in the darkest chaos. I wonder if we cannot apply this same reasoning to the moral chaos that follows when there is no longer any real threat of eternal damnation. It is then that ‘all Hell breaks loose’. It has been loose for decades now, and the Church is powerless to constrain it unless she resumes the vigorous preaching of what her Divine Spouse bequeathed to her. It’s not difficult. The words of the Gospel are normative in every age. We cannot make them better, nor do they need any revision.

Washington was right when he said that men will not behave if there is no sword of justice hanging over their heads. Sarah was right when he said it was God or nothing. It’s all so very simple. The future, not only of the Church, but of civilisation itself, hangs in the balance. The outcome will depend on whether or not we have the humility to admit that we have gotten it all wrong, and the courage to march resolutely back to that fork in the road where we took the wrong turn.

[1] I highly recommend reading about the following visions of Hell: St Teresa of Avila, in her Life, chapter 32, tells of how she was once taken to Hell and what she experienced there; the Mother of God showed a vision of Hell to the children of Fatima on 13 July 1917; St Faustina Kowalska, like St Teresa, was taken to Hell and had a similar experience that she recounts in her Journal (# 741).

[2] ‘A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic — on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg — or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronising nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to’ (C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, part II, The Shocking Alternative).

[3] Here is the passage in question from Lumen Gentium, 48: ‘Since however we know not the day nor the hour, on Our Lord’s advice we must be constantly vigilant so that, having finished the course of our earthly life, we may merit to enter into the marriage feast with Him and to be numbered among the blessed and that we may not be ordered to go into eternal fire (cf. Mt 25:41) like the wicked and slothful servant (cf. Mt 25:26), into the exterior darkness where “there will be the weeping and the gnashing of teeth” (cf. Mt 22:13 and 25:30). For before we reign with Christ in glory, all of us will be made manifest “before the tribunal of Christ, so that each one may receive what he has won through the body, according to his works, whether good or evil” (2 Cor 5:10) and at the end of the world “they who have done good shall come forth unto resurrection of life; but those who have done evil unto resurrection of judgment” (Jn 5:29)’.

[4] Two examples among far too many to cite here: ‘If thy eye scandalize thee, pluck it out. It is better for thee with one eye to enter into the kingdom of God, than having two eyes to be cast into the hell of fire: where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not extinguished’ (Mk 9:46-47); ‘then he shall say to them also that shall be on his left hand: Depart from me, you cursed, into everlasting fire which was prepared for the devil and his angels. And these shall go into everlasting punishment: but the just, into life everlasting’ (Mt 25:41 and 46).

[5] Our Lord told the Good Thief: This day thou shalt be with me in paradise (Lk 23:43), which makes no sense at all if the descent of Christ into Hell was not a glorious event.

[6] The informed reader will no doubt have recognised the teaching, in the first instance, of Karl Rahner, and in the second, of Hans Urs von Balthasar.

[7] Spiritual Exercises, # 65.