A quick perusal of the numerous fundamental dogmatic theology manuals penned in the 19th and early 20th centuries presents a constant feature: there is always a treatise devoted to the Church. This treatise is sometimes called tractatus de vera religione – treatise on the true religion. The very expression will sound offensive to many ears in our day. But why should this be so? If there is a God (there is), He can only be one; if there is only one God, it makes sense that there be only one religion, for the simple reason that an eternal, infinitely perfect God could not possibly reveal contradictory truths to different peoples at various stages of history. God is not a scoundrel who fathers several families. We can safely conclude that if there is only one religion, that religion is true, and this, by the very fact, makes all other religions the opposite of true, that is to say, false.

In a world that prides itself on pluralism and inclusiveness, this statement comes as a shock. That those who are not members of the true religion would have problems accepting that their religion is not true comes as no surprise. What is surprising is that the members of the true religion would have qualms with it. It would seem safe to say that for many Catholics today, to declare one’s religion to be true and all the others false would be seen as egotistic, bigoted, unsociable and even insulting. And yet it is so. This particular type of Catholic has been around for a long time, but an objective study of the last 60 years reveals that their numbers have increased exponentially since Vatican II.

Multiple Complex

In my two preceding articles, I pointed to two complexes that have a grip on many contemporary Catholics. The first is an enduring orientation complex due to the turning around of the altars, an unprecedented and unjustifiable novelty in contradiction with the entire tradition of the Church. The second is an identity complex that plagues the Catholic mindset since Vatican II, several of whose texts conveyed equivocal notions on the Church and her mission. Before this, I had already noted the shift in pastoral perspective launched mainly by the pastoral constitution Gaudium et spes, which stressed in an undue manner the positive aspects of the modern world, and occasioned a novel attitude of singing in chorus with the world instead of challenging it to mend its ways.

What we have then before us is this: a large number of Catholics no longer really know who the Church is, where she is going or what she is doing. And this inevitably leads to the need to gather periodically in talkfests which achieve little more than depleting the already crippled funds of the Church, which should be used for feeding the poor, preaching the Gospel to those who have never heard it and re-evangelising those who, though baptised, are now drifting along like sheep without a shepherd. The present-day cacophony, which has been dressed up in an appropriately Orwellian disguise under the name of ‘synodality’, is the logical and inevitable result of subtle theological changes sanctioned at least implicitly by the Council and which, over time, have destabilised the mentality of so many Catholics.

The Spectre of the Past

Today, I turn my attention to another aspect of modern Catholicism that stems directly from the pastoral approach of Vatican II. It concerns the way the Church views non-Christian religions, especially as laid out in the conciliar Declaration Nostra Aetate, the new charter for the Church’s dealings with religions that do not share her faith in Christ Jesus. The bulk of Nostra Aetate is dedicated to explaining what we have in common with other religions such as Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism. As would be expected, particular emphasis is laid on our relationship with the Jewish People. Like much of the conciliar teaching, the declaration can only be understood against the backdrop of the Cold War period and the growing desire for mutual understanding among nations and religions. The tone is definitely one of conciliation and harmony; nothing is said about converting the adepts of other religions. As its title indicates, Nostra Aetate is not a dogmatic constitution (like Lumen Gentium or Dei Verbum) but a simple declaration. This is significant, for it means that it lays no claim to being a theological treatise; instead, it seeks to inaugurate a period of relations with other religions deemed more in line with modern needs and ways of thinking, a pastoral approach that leaves Church dogma intact.

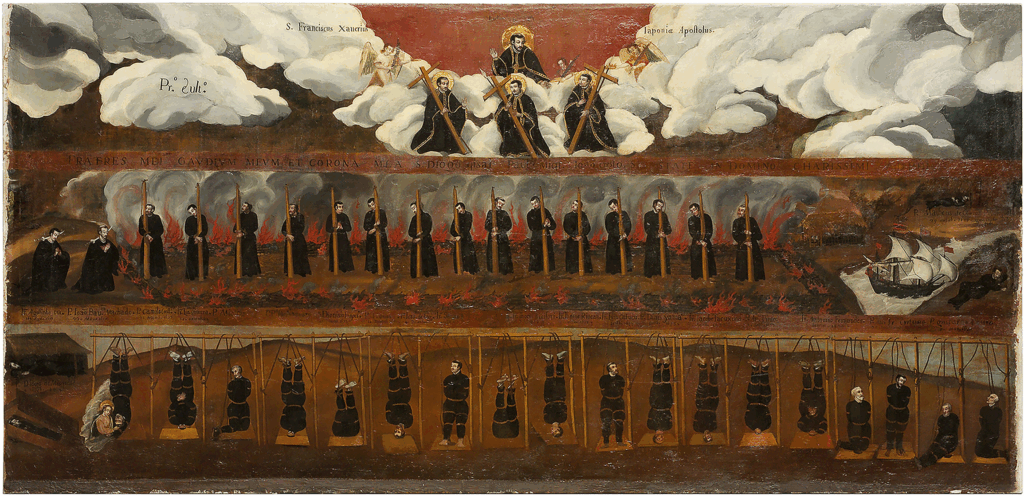

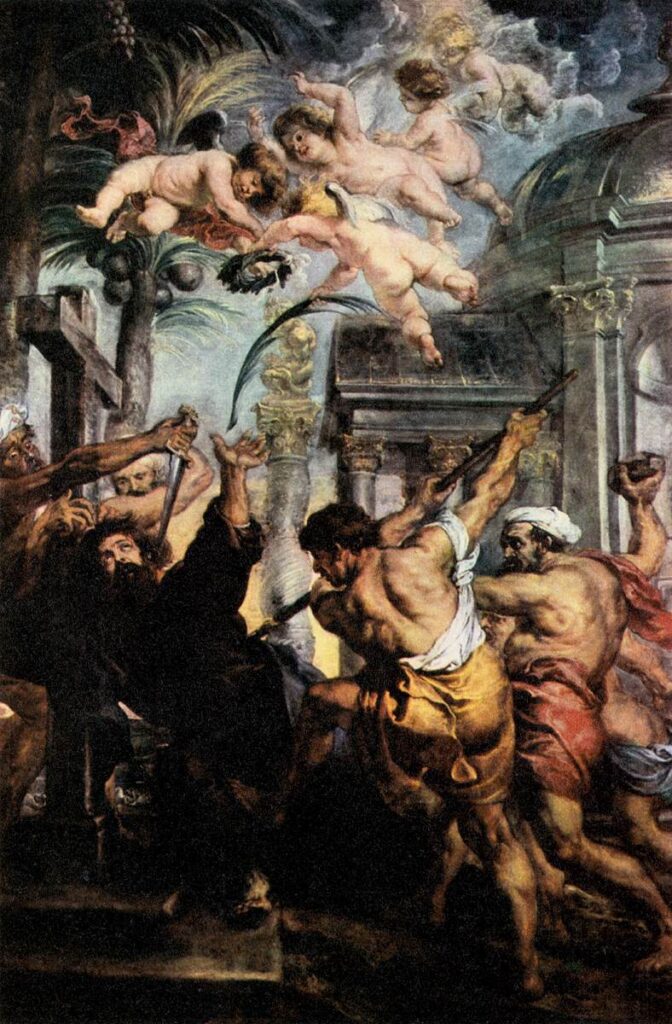

In a world on the verge of a not-so-unthinkable nuclear disaster, in 1965 the foremost priority seemed to be getting along with and respecting other religions. The spectre of the Crusades, the Inquisition, and the Wars of Religion – often in deformed ways that did not do justice to the real history – was still hanging over the memory of many in the Church as moments of particular gravity that must never happen again. Furthermore, in a world which had seen the rise of militant atheism, to many of the Council Fathers it was thought essential that all religions speak with one voice about belief in a Supreme Being. To summarise the teaching of Nostra Aetate, we could say that the Council wanted to avoid any potential conflict with anyone. Such was the spirit of the times that prompted the declaration and the main reason for which it described other religions only in positive terms.

A New Paradigm

Two months after the promulgation of Nostra Aetate, another declaration saw the light of day, Dignitatis humanae, which insisted that each person has a natural right to religious freedom. Written in the same spirit as Nostra Aetate, and no doubt intended to be a complement to it, Dignitatis humanae boldly set out to do what no Catholic document had ever done, namely, affirm a natural right to dissent from the true religion and to publicly practice a false religion. The thinking was this. Since human beings are endowed with reason and free will, it is immoral to force a person to embrace a faith they do not adhere to interiorly. Furthermore, if we need to gather all religions today in harmony against growing atheism, then we must recognise that people have a right to believe whatever religion they think is true and to promote it publicly by building places of worship.

The Second Vatican Council, then, decidedly took the path of guaranteeing the freedom, not only of the Catholic Church – which she had always done – but of any and every other religion. The conclusion that was drawn by many and which seemed to impose itself is this: if the Church insists that we are free to practice any religion and if we are to get along with the members of all other religions, then what is the most important is simply to be consistent with one’s beliefs and respect those of others. All that matters in the end, according to this novel approach, is being sincere in one’s beliefs.

Free Church, Free State

In some parts of the world, this is precisely the manner of thinking of most people who would consider themselves to be religious. In the United States of America, where religious freedom was one of the founding principles of the nation, all religions are respected and allowed total freedom to promote their beliefs. If you drive down the streets of any American city, you will encounter a whole series of buildings dedicated not only to the services of Christian denominations but also of synagogues, mosques and any number of other houses of worship. It was precisely this sort of life in common (‘free church in a free state’ was the expression used in the 19th century) that was presented as the model by the principal architect of Dignitatis humanae, the American Jesuit, Fr John Courtney Murray.

It is not at all evident how the new attitude promoted by the Council can be reconciled with the traditional view. Rivers of ink have tried to explain it. There are also, however, in the very texts of the Council itself elements that seem to oppose this new mentality. One of them is found in the opening paragraph of Dignitatis humanae itself, in which it is said that the Council’s teaching ‘leaves untouched traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty of men and societies toward the true religion and toward the one Church of Christ’.[1]

This apparently anodyne statement turns out to contain an enormous challenge for the theologian and for anyone who wants to make sense of Catholic doctrine and the conciliar teaching. The main difficulty resides in the fact that the traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duties of men toward the true religion and the one Church of Christ teaches clearly that since there is one God and one Saviour, there can only be one religion. All men are bound to seek out this religion and adhere to it with all their strength. Furthermore, false religions cannot have the same rights as the true religion to promote their teachings. Indeed, as Pius XII had clearly enunciated just a few years before: ‘that which does not correspond to truth or to the norm of morality objectively has no right to exist, to be spread or to be activated’.[2] Leo XIII had already taught in the same vein: ‘Whatever is opposed to virtue and truth may not rightly be brought temptingly before the eye of man, much less sanctioned by the favour and protection of the law. A well-spent life is the only way to heaven, whither all are bound, and on this account the State is acting against the laws and dictates of nature whenever it permits the license of opinion and of action to lead minds astray from truth and souls away from the practice of virtue’.[3]

The teaching of Tradition is clear, and the Council did remind us of it, barely, but at the same time, it inaugurated a mindset according to which it is no longer fashionable to state clearly the truths that displease; these are often hidden like a needle in a haystack, allowing those who wish to ignore them full freedom engage in dialogue and no longer be obliged to militate for the truth that saves.

The ‘Spirit’ of Assisi

Nowhere did this appear with greater emphasis than in the gatherings convoked at Assisi from 1986. As is well-known, the original idea of these came to John Paul II in order to foster peace. His thinking was that if we all come together to the same place, and if each of us prays to our own god together, we are bound to be heard. What the pope never explained was how prayers addressed to false gods can be pleasing to the true God. Nor did he explain how the Sovereign Pontiff could licitly put Catholic edifices at the disposal of false religions so that they could practice their false worship therein. We must admit that one is hard pressed to come up with a good answer as to why this did not violate the First Commandment. The explanation given at the time that the invitees ‘did not come to pray together but to be together to pray’ convinced few, and while we can hope that the participants were all of good faith in their beliefs and, subjectively speaking, were acting according to a good, though erroneous conscience, the objective reality remains that the event itself seemed to say loud and clear: the Catholic Church approves the worship of other religions.

Anyone familiar with the movement of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre knows how pivotal the first Assisi event was in his decision to proceed with the consecration of bishops without papal mandate. For Lefebvre, the Pope had sinned gravely and publicly against the First Commandment by not only allowing and promoting false worship in Catholic Churches, but even by publicly praying with the representatives of false religions. The famous kissing of the Koran by the same pope on 14 May 1999, which remains a stumbling block for many, was inspired by the same thought that had given rise to Nostra Aetate: since every religion contains some good, we can show reverence for that good while not condoning the error it contains. Unfortunately, this reasoning fails the test of the scholastic dictum: bonum ex integro, malum ex quocumque defectu – A thing is good if every part of it is good; a thing is bad if only one part of it is bad.[4]

An honest sifting through the magisterial acts of John Paul II reveals that he wanted all souls to come to Christ and the Catholic Church. This is made clear from such texts as this: ‘No one can enter into communion with God except through Christ, by the working of the Holy Spirit. Christ’s one, universal mediation, far from being an obstacle on the journey toward God, is the way established by God himself, a fact of which Christ is fully aware. Although participated forms of mediation of different kinds and degrees are not excluded, they acquire meaning and value only from Christ’s own mediation, and they cannot be understood as parallel or complementary to his’.[5]

Or again in the Catechism he published in 1992: ‘God desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth (1 Tm 2:3-4); that is, God wills the salvation of everyone through the knowledge of the truth. Salvation is found in the truth. Those who obey the prompting of the Spirit of truth are already on the way of salvation. But the Church, to whom this truth has been entrusted, must go out to meet their desire, so as to bring them the truth. Because she believes in God’s universal plan of salvation, the Church must be missionary’.[6]

He was also fond of quoting this major text from the Decree on the Mission Activity of the Church Ad Gentes:‘This missionary activity derives its reason from the will of God, who wishes all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. For there is one God, and one mediator between God and men, Himself a man, Jesus Christ, who gave Himself as a ransom for all (1 Tm 2:45), neither is there salvation in any other (Acts 4:12). Therefore, all must be converted to Him, made known by the Church’s preaching, and all must be incorporated into Him by baptism and into the Church which is His body. For Christ Himself by stressing in express language the necessity of faith and baptism (cf. Mark 16:16; John 3:5), at the same time confirmed the necessity of the Church, into which men enter by baptism, as by a door. Therefore those men cannot be saved, who though aware that God, through Jesus Christ founded the Church as necessary, still do not wish to enter into it, or to persevere in it. Therefore though God in ways known to Himself can lead those inculpably ignorant of the Gospel to find that faith without which it is impossible to please Him (Heb. 11:6), yet a necessity lies upon the Church (1 Cor. 9:16), and at the same time a sacred duty, to preach the Gospel. And hence missionary activity today as always retains its power and necessity’.[7]

Clearly the Fathers of Vatican II thought there was no contradiction involved in, on the one hand, believing that Jesus Christ is the only Saviour and that to be saved one must believe all that He revealed and belong to the Church He founded, and on the other hand, believing that not only can the prayers of the adepts of false religions be good and acceptable to God, but that the Catholic Church can publicly approve of those prayers and no longer just tolerate them as she did in the past. The facts are there for anyone to verify. In upcoming articles, an attempt will be made to analyse and explain how this happened, and how the Council Fathers did not think they were violating the principles of logic.

Straining Forward to What Lies Ahead (cf. Ph 3:13)

At this stage, the question we need to ask ourselves is this: going forward, is it possible to maintain the Council’s pastoral approach at the risk of weakening further the faith of the ordinary Catholic in the pew who, when he sees the Pope praying with the infidel as did John Paul II or declaring that God wills all religions as Francis did, can only conclude that all religions are equally valid, an unequivocally heretical statement? Some have resorted to considerable mental dexterity in order to make it appear as if nothing has changed, thereby absolving Church leaders of inherent contradictions in their thought. One thing is certain: for too many of the faithful, the Church no longer proclaims herself to be the only path to salvation, for all religions have something to offer, and since we assume that everyone is of good faith, we need to let everyone worship as they please and assume everyone will go to Heaven. While this may seem comforting to many, it does not correspond with what God has revealed to us, nor does it fit in with Tradition, the countless generations of Popes, Bishops and missionaries going back to the apostles. Ut sonans, it is false and cannot produce good fruit. By their fruits you shall know them (Mt 7:20).

So, what are we to do? The confusion must end, and it can. All it would take is for the Pope to muster enough courage to clarify certain points that the teaching of Vatican II has obfuscated in the minds of many. Mind you, this has been done to a certain extent. John Paul II’s encyclical Redemptoris Missio, as well as the declaration Dominus Jesus,[8] were a good start, as both had as their primary objective to counter the attitude that has led so many to religious indifferentism. And yet, neither of those documents went far enough. Indeed, the underlying issue is really that of the conversion and eternal salvation of souls, which these documents leave pretty much out of the picture. So it is with every pastoral orientation – one runs the risk of focusing so much on one element of a truth that many other truths, and sometimes more important ones, are left in the dark.

While the Magisterium of Vatican II and the popes that have followed admit of the existence of Hell and the possibility of being lost forever, there is nevertheless an ambient fundamentally optimistic view of salvation that seems to reverse the words of Our Lord in Matthew 7:13-14: Enter by the narrow gate. For the gate is wide and the way is easy that leads to destruction, and those who enter by it are many. For the gate is narrow and the way is hard that leads to life, and those who find it are few. The contemporary reading of those two verses is more like this: Narrow is the gate and strait is the way that leadeth to destruction, and few there are who go in thereat. How broad is the gate, and easy is the way that leadeth to life: and so many there are that find it!

We must be honest and admit that most people in the church today speak and act as if this were indeed the true teaching of Our Lord. They seem incapable of taking seriously His numerous grave admonitions, no doubt because they put more confidence in their own wishful thinking and the adroitness of their novel theologians than in the clearly enunciated words of the Son of God.

This cannot go on. From the Pope to the simplest priest, we must recover the fire that animated the apostles when they did not fear to tell the Jews: This people’s heart has grown dull, and with their ears they can barely hear, and their eyes they have closed; lest they should see with their eyes and hear with their ears and understand with their heart and turn, and I would heal them. Therefore let it be known to you that this salvation of God has been sent to the Gentiles; they will listen (Acts 28:25-28).

There are souls out there waiting for the truth and avidly assimilating it when it is presented in all its purity without being watered down by pastoral initiatives that weaken it. Future generations will look back and wonder how we could be so naive as to imagine that modern man alone, of all periods in history, can thrive on contradictions. We need to pray that the prophecy of Our Lord to the Pharisees be not fulfilled for us too: The kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a people producing its fruits. And the one who falls on this stone will be broken to pieces; and when it falls on anyone, it will crush him (Mt 21:43-44).

[1] Vatican II, Declaration Dignitatis humanae, 7 December 1965, no. 1.

[2] Pius XII, Discourse to the National Convention of Italian Catholic Jurists, 6 December 1953.

[3] Leo XIII, Encyclical Immortale Dei, 1 November 1885.

[4] See my preceding article https://oriensjournal.com/integral-christianity/

[5] John Paul II, Encyclical Redemptoris Missio, 7 December 1990, no. 5.

[6] Catechism of the Catholic Church, p. 851.

[7] Vatican II, Decree Ad Gentes, 7 December 1965, no. 7.

[8] Cf. Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Declaration Dominus Jesus, 6 August 2000.