Last month, we were reminded that there is a potential modernist lurking in each of us, and that whenever we make ourselves the centre of our preoccupations, we are, in some way, already a modernist. From this perspective, we can say that already in the Garden of Eden modernism was conceived, even if the full scale of its bad fruits would be made known only with the passage of time.

We were, however, left somewhat in suspense about how to get out of the labyrinth of ever-evolving egotisms that are the breeding ground of modernism. We know that God is the ultimate answer. We also know that we are much more than the passing whims of our fallen nature. Anchoring our soul to the one true God is obviously the only way to find stability, peace and salvation, but some may be wondering how to do this on a practical level. How can we avoid being modernists in our daily lives? We mentioned Plato and the contemplation of the eternal Forms or Ideas, but for most people who are not philosophers, this does not offer any practical means of proceeding. How many people have read Plato, and of those, how many understand him?

Plato and Aristotle

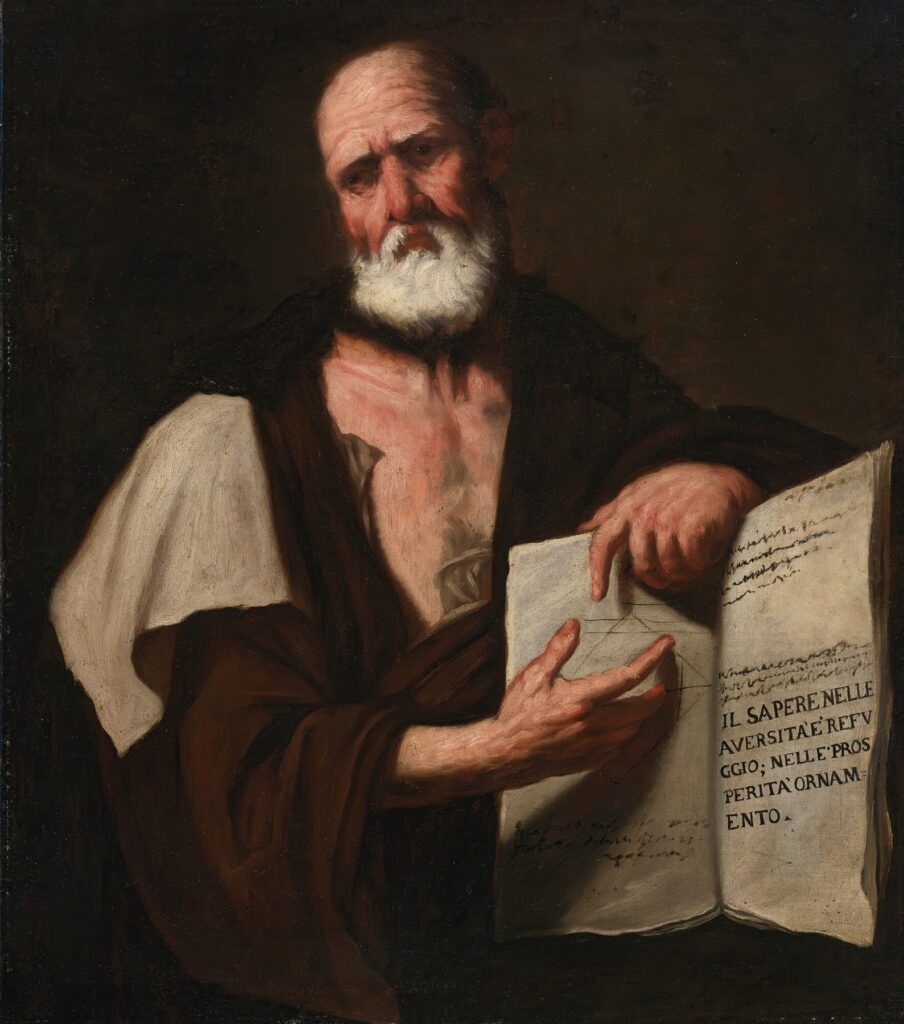

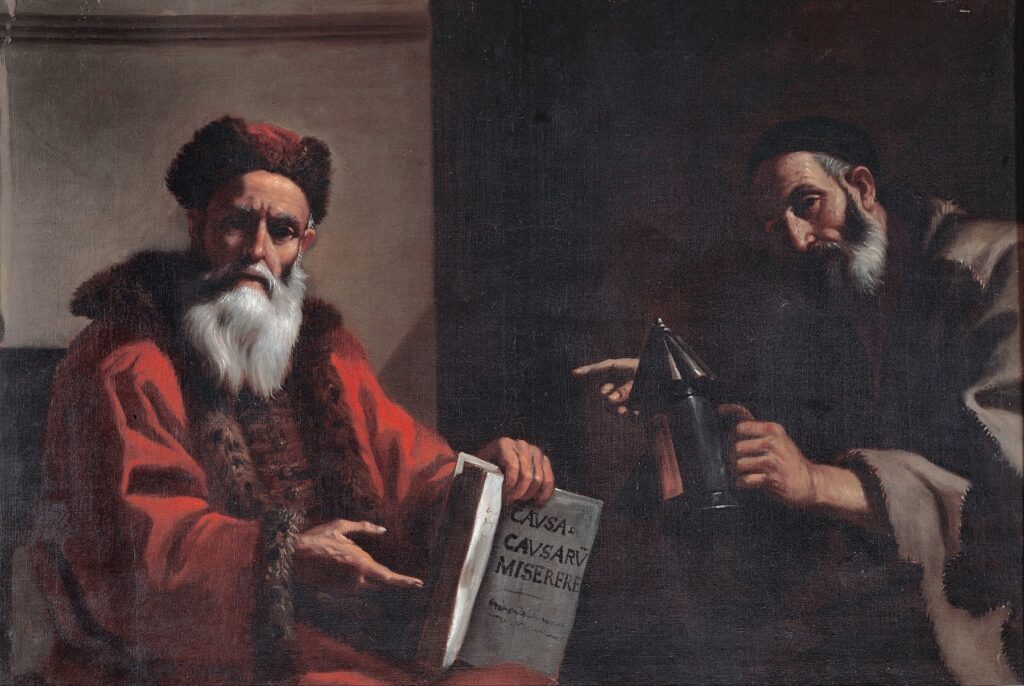

It is important to note furthermore that when Pope St Pius X condemned modernism and proposed remedies for it, he turned our attention not so much to Plato as to Aristotle. He did this by following in the footsteps of Leo XIII and promoting the study of St Thomas Aquinas praesertim in re metaphysica – above all in the realm of metaphysics. While Plato is lofty in his consideration of eternal realities, Aristotle is more down-to-earth about how we can actually live good lives without being the playthings of our passions. While Plato played a priceless role in calling humanity to discover in us, around us and above us, the unchanging, invisible world to which we are ultimately destined, his insistence on these could be seen as leaving aside the visible world as something that is not really worthwhile. Many of the Fathers of the Church were attracted to Plato precisely because of this other-worldliness; they saw him as a Christian before the letter, one who lived in the world without being of it. Furthermore, it was an easy step to see in the Platonic forms various aspects of the divine perfections.

But there were some incompatibilities. For example, as is well known, in Plato’s ideal world, as he describes it in The Republic, there should be no artists, because art, for him, is three steps removed from the ultimate Forms. Our world itself being but a shadow of the real world of Forms, any artwork that would reproduce such shadows is hardly worth our time and effort. It’s easy to see how this can lead to little or no esteem for the world that surrounds us, this world that God Himself created and in which He deigned to take our humanity. This is precisely why Plato, while leading in the right direction, is not enough. It is why St Thomas Aquinas devoted his life to expounding and adapting Aristotle, showing that his thinking, more than that of Plato, is capable of teaching the Christian how to not only achieve beatitude in the eternal world of God, but also how to live a good life in this world with its realities that are not shadows, but real things that are good because they are created by God, but can lead us astray because our nature has fallen from its primitive purity and is inordinately attracted to the realm of the flesh. While many of the Fathers of the Church saw Aristotle more or less as a pagan, Plato being the ‘divine’, Aquinas rightly saw that far from being one to avoid, Aristotle offers us invaluable, and indeed, essential tools for knowing the real: who we are, what the world is, and how we can live in this world in a rational way that, while not sufficient to be a Christian, certainly predisposes to receiving the grace of conversion. The same God who gives supernatural grace is the one who created the rational world, and therefore, there can be no incompatibility between them.

Things Are More Than Names

To know what is real, and to distinguish it from what is not: such is the mighty task that Aristotle gave himself and in which he succeeded better than any other philosopher. While Plato situated the true ideal forms of things in another world, Aristotle taught that the form of a thing is in that very thing itself, and that things have a nature in common with each other. A tree has in common with other trees the fact that it is a tree, even though there are various kinds of trees. The same can be said of dogs, cats and humans, etc. The nature of a thing can be discovered by abstracting from its accidental properties in order to find its essence. Based on this philosophy, the study of nature was made possible. At the same time, so was the development of the Natural Law, which is nothing but the reflection in creatures of the eternal law existing in the Godhead. Indeed, discourse on the Natural Law is only possible if there is such a thing as nature.

Tragically, the very concept of nature was shattered by the nominalist crisis initiated by William of Ockham (1287-1347). For Ockham, nature is just a construct, names that we use to put things into categories. For Ockham, humans do not share a unique human nature; each human is his own entity and has only certain similarities with others. With the loss of the concept of nature, individual things were just that, individuals, without any unity of nature with similar beings. The consequences of such a teaching were not long in coming: if each human is his own nature, then there is no general set of laws that applies to all humans, and we find ourselves in a lawless world in which the nature of things no longer establishes any boundaries or guidelines. Reason and law can no longer prevail, and all that is left is raw power: might is right.

Nominalism was one of the most devastating steps towards the dismantling of philosophical thought because it made any discourse on the nature of things impossible. It also opened the path to any new philosophy that sought a basis in only partial perspectives of reality. If modernism owes much to modern philosophical trends, this was made possible only by the advent of nominalism, which is why one of the most fundamental responses to modernism is to return to Aristotle and Aquinas. Both Leo XIII and Pius X were spot on, but unfortunately with a few notable exceptions their urging has been ignored.

The Owner’s Manual

Why is this so important? Quite simply, because the breakdown of the human mind begins when there are no longer any universal concepts that are shared among humans. If each individual is just an individual, then each person becomes his/her own little world. From there, it’s a short step to the modernistic concept of vital immanence that we dealt with last month.

On the practical level, then, the forming of the mind and its protection against modernism starts with the very simple realities of day-to-day life and the acknowledgment of the nature of things. All rabbits take part in the same rabbit nature, and this is why all rabbits in the world do rabbity things. The same goes for dogs, cats, horses, etc. There is a common nature that removes individuals from the arbitrariness of pure individuality and places them squarely within an order they did not create and that they respect and always will. You will never see a dog fly, nor an eagle burrow in the earth. You will not find a horse that barks, nor a spider that builds dams on rivers.

When we apply this to humans, we see that human nature is the same in all humans, regardless of the colour of their skin or the shape of their faces. All human beings throughout history have always acknowledged having in common values that everyone accepts. Every human knows instinctively and without being told that certain things are not compatible with being a good human. A good human who has not lost his mind wears clothes, does not kill innocent fellow humans; he does not steal or tell lies or sleep with his neighbour’s wife; he does not abandon his parents when they are old, etc. Even if humans sometimes do these things, they know they are wrong, and they feel shame when they do them. Why is this so? Because we all share the same human nature created by God in a certain way with certain manners of functioning: we are all born with an inbuilt ‘how to use’ owner’s manual.

What then are the basic remedies for getting our own soul out of this mindset, which we call modernism, and keeping it out, and then of helping others find their way out of the same? Three practical points are given here which are so fundamental that without them a truly human and Catholic life is not possible, but with them one can safely set out on the path of salvation and remain beyond the reach of the most nefarious effects of modernism.

There is a God, and It’s Not You.

This may sound facetious, but it isn’t. Any serious spiritual life begins here: the conviction that the universe did not, could not, make itself and therefore was created by a transcendent God, and that this God is not me–this is the beginning of conversion, because Lucifer’s initial Non Serviam – the cause of his eternal damnation – was essentially a rejection of this truth. If we truly believe it, it goes a long way towards fixing most of our problems. If someone not only accepts this but holds to it firmly and makes it the basis of their life, they are already on the road to becoming a good person. If ever you find yourself falling back into bad ways, repent and turn back to God. God always forgives a truly contrite heart.

Acquiesce to Reality.

Accept things the way they are. Accept being in a world you did not create and in which you do not call the shots. By this, I do not mean to not make efforts to fix what is broken and change patterns that are bad. What I mean is that, despite all our efforts to mend ourselves and the world, we are all irretrievably wounded by Original Sin – a dogma, by the way, that modernists loathe, but more on that later –, and the full restoration of our humanity will not take place until the end of time and the final resurrection. In the meantime, one of the most fundamental steps toward conversion and sanctity is to accept things as they are rather than revolt against them. For example, if you happen to have some physical infirmity that doctors can do nothing to help, accept it, do not grumble about it or revolt. If your spouse turns out to be a very different person from the one you thought you had married, accept them the way they are and don’t think that you deserve better. Perhaps you do, but perhaps you don’t, and in any event, grumbling about it will get you nowhere. Bend over backwards to make your marriage work. Never forget that the first one to not acquiesce to reality was Lucifer, the angel of light, who was not content with being such an extraordinary creature placed over many others, but wanted to be more–he wanted to be God. Never forget that Eve’s sin was essentially wanting something else than what she had. She had a million trees to eat fruit from in the Garden of Eden, but she convinced herself that she just couldn’t be happy if this one tree were denied her. She refused reality – that there is a God, it was not her and that therefore she had limitations–, and in so doing, wreaked havoc for all of humanity. Acquiesce to reality–Nature never forgives.

Accept Your Mother As She Is.

The Church, too, has a nature. It’s what we call her ‘divine constitution’, that is to say, the way Christ made her. The Church, like any institution that includes fallen humans, has many problems. Everyone could think of any number of ways we would go about ‘fixing’ the Church. The fact of the matter is, however, that the Church does not belong to us, and therefore we cannot ‘fix’ her. She has a nature, and that nature is that she belongs to Jesus Christ, her eternal Bridegroom, who never abandons her. We are simply sons and daughters of the Church, and by wishing to ‘fix’ her we would really be usurping the role of Christ; it would be like a son violating his own mother under the pretext that his father is not doing his job. The best thing we can do for our mother is to avoid sin and become as holy as we can in the state of life that is ours. This can happen only if we respect the nature of the Church. Three principal points deserve mention here – others being reserved for a future instalment:

A) Hold firm to the dogmatic teaching of the Church in its entirety. In other words, accept every single dogma that has been defined by the Church. Do not play the smart alec who thinks he knows better, and above all, do not play the modernist game of paying lip service to Church teaching, using her language, and then saying something entirely different from what she actually teaches. When we deal with the Church, we are dealing with a supernatural institution endowed by Christ with a supernatural instinct for what is true and what is not. Once something has been dogmatically and solemnly defined by the Church, it does not change, even if our understanding of it can progress. We must always hold the same dogma and the same meaning, unlike the modernist who uses the same words but empties them of their meaning to suit his own agenda.

B) Embrace the moral teaching of the Church in all its parts and don’t try to find loopholes. We can safely say with Archbishop Fulton Sheen: ‘Atheism, nine times out of ten, is born from the womb of a bad conscience. Disbelief is born of sin, not of reason’. Ultimately, modernism is a form of atheism because it leads straight to pantheism as St Pius X made clear in Pascendi. Living a good moral life is essential for not falling into practical forms of modernism.

C) Do not consider the liturgy to be a playground. The reason the modernist thinks it is is that his ever-evolving view of reality means that worship must follow an ever-evolving pattern, completely disconnected from reality because it is severed from the nature of things. In reality, the liturgy is like a living organism that, while remaining the same, has been enriched over the centuries. Just as taking a living organism apart in order to rebuild it in a way that suits us better is to kill it, so deconstructing and then reconstructing the liturgy, or playing around with it as it suits us, is to destroy it.

If we consistently do these simple things, we will find that in short order, life makes more sense, we are not tossed around by an evolving cosmos or religious feeling, we stand firm on that Rock which is Christ, the God-Man, the eternal Bridegroom of the Church, against whom all the turbulent waves of confusion and error are powerless – to Him be glory for all eternity.