Saint John Henry Newman and the Development of Doctrine

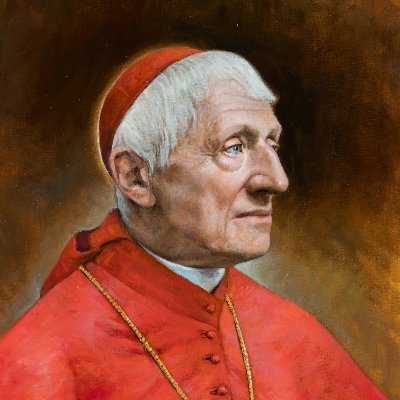

An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845, revised edition 1878) has to be ranked among the most important theological works of the last two hundred years. It has been translated into French, German, Italian, Polish, Slovene and Spanish. Its author began life in London at the start of the 19th century, was reared as an Evangelical Anglican, was briefly a Liberal, studied at Oxford, held a curacy as a minister of the Church of England, became a leader of a High Church movement—and ended life as a Cardinal of the Holy Roman Church in Birmingham. How he arrived there is a story of development in itself.

Newman’s life

John Henry Newman was born in the City of London, 21 February 1801, the eldest of six children: three boys and three girls. He was educated at Ealing School, London, and Trinity College, Oxford. Elected a fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, in 1822, he became vicar of the university church of St Mary’s in 1828. In 1833 he began, with a group of other Anglicans, a series of writings, Tracts for the Times, in a movement to restore certain ancient Christian beliefs and traditions in the Church of England. Their work came to be known as the Oxford Movement, or Tractarian Movement; but after Newman was condemned by the Anglican bishops for his controversial Tract 90, which attempted to interpret the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England (1571) in a Catholic sense, he withdrew in 1842 to monastic seclusion at Littlemore, Oxford, intending to retire from public writing until he could settle upon his final religious position. It was there he wrote this Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. Without completing it fully, he stopped writing, in order to be received into the Catholic Church on 9 October 1845.

Newman then studied for the Catholic priesthood in Rome at the College of Propaganda Fide. In Rome, he met Pope Pius IX who was in the opening years of what would become the longest pontificate of Church history, 1846-1878. Newman was ordained a priest in 1847. Returning to England, he founded the Birmingham Oratory in 1848, a community of priests following the rule of St Philip Neri. In 1851 he was appointed first Rector of the Catholic University of Ireland, and held that position until he resigned in 1858. His Dublin lectures and articles on tertiary education were eventually published as The Idea of a University (1858).

Newman was a prolific writer of letters, tracts, hagiography, historical studies, sermons, poems, prayers and meditations, and even two novels. His Parochial and Plain Sermons, given as an Anglican curate, are still in print, and—it is safe to say—would be the only 19th century homilies widely read today. Among other important writings of Newman are his intellectual autobiography Apologia Pro Vita Sua (‘A Defence of His Own Life’, 1864), written in response to a public personal attack by Charles Kingsley, and An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent (1870), a philosophical exposition of the nature of religious faith.

Amid most years of his many writings and controversies, Father Newman continued to perform priestly work in his parish, first in the inner city of Birmingham and later in the better-off suburb of Edgbaston where the Oratory was finally established. He offered Mass, heard Confessions, preached the word of God, conducted baptisms, marriages and funerals, and ministered to the troubled, the sick and the dying.

In 1878, Cardinal Gioacchino Pecci was elected to the papacy and took the name Leo XIII. He began to address the modern world in a positive teaching style very different to that of Pius IX. In the following year, 1879, he made Newman a cardinal. Newman went to Rome for the occasion, and returned to the Oratory of Birmingham to resume his priestly life.

Cardinal Newman died at Edgbaston on 11 August 1890. For his holy and faithful Catholic life, he was beatified by Pope Benedict XVI in Birmingham in 2010, and canonised by Pope Francis in Rome in 2020.

Newman’s early interest in the development of dogma

In was first in The Arians of the Fourth Century (1833), written in 1832, that Newman, aged 31, spoke of the effect of the application of human reason to revealed matters of faith, in his consideration of how ancient Christian creeds came to be formulated to meet the needs of the times:

As the mind is cultivated and expanded, it cannot refrain from the attempt to analyze the vision which influences the heart, and the Object in which that vision centres; nor does it stop till it has, in some sort, succeeded in expressing in words, what has all along been a principle both of its affections and of its obedience … Thus the systematic doctrine of the Trinity may be considered as the shadow, projected for the contemplation of the intellect, of the Object of scripturally-informed piety: a representation, economical; necessarily imperfect, … kept in the background in the infancy of Christianity, when faith and obedience were vigorous, and brought forward at a time when, reason being disproportionately developed, and aiming at sovereignty in the province of religion, its presence became necessary to expel an usurping idol from the house of God.

If this account of the connexion between the theological system and the Scripture implication of it be substantially correct, it will be seen how ineffectual all attempts ever will be to secure the doctrine by mere general language. It may be readily granted that the intellectual representation should ever be subordinate to the cultivation of the religious affections … But what is left to the Church but to speak out, in order to exclude error? Much as we may wish it, we cannot restrain the rovings of the intellect, or silence its clamorous demand for a formal statement concerning the Object of our worship. If, for instance, Scripture bids us adore God, and adore His Son, our reason at once asks, whether it does not follow that there are two Gods; and a system of doctrine becomes unavoidable; being framed, let it be observed, not with a view of explaining, but of arranging the inspired notices concerning the Supreme Being, of providing … a connected statement.[1]

Later in the same chapter, Newman says that the ancient orthodox Christians

pursued the intellectual investigation of the doctrine [of the Trinity], under the guidance of Scripture and Tradition, merely as far as some immediate necessity called for it … Thus they developed the notion of substance against the Pantheists, of the Hypostatic Word against the Sabellians, of the Internal Word to meet the imputation of Ditheism …[2]

As time went on, Newman explains, experience and controversy made them refine and adjust their expressions, and become more consistent; in other words, to develop a system. The Arians of the Fourth Century was Newman’s first book and is a major theological work in its own right. It is interesting, in passing, to note Hilaire Belloc’s praise of it:

Now I turn over and over again to that book of Newman’s written in his early vigour, The Arians of the Fourth Century, and am lost in astonishment at the admirable quality of the prose. Here is a man writing upon a subject which only a few scholars consider; which has nothing in itself of general interest; which involves a quantity of tedious detail, yet the diction is such that it carries you on like a river, without effort: an amazing achievement.[3]

In 1834, in Tracts for the Times 41, Newman looked explicitly at the notion of theological developments. The layman in the dialogue of that Tract says to the cleric:

I think I quite understand the ground you take. You consider that, as time goes on, fresh and fresh articles of faith are necessary to secure the Church’s purity, according to the rise of successive heresies and errors. These articles were all hidden, as it were, in the Church’s bosom from the first, and brought out into form according to the occasion. Such was the Nicene explanation against Arius …

Once more, in 1836, in Tracts for the Times 79, on Purgatory, Newman looked at doctrinal developments when he compared the ancient Fathers on the intermediate state of the soul to the formulations in the Roman Catechism of 1566 and later theologians such as St Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621). Newman quotes the English Cardinal, St John Fisher (1469-1535), who made a very significant statement on doctrinal development:

It weighs perhaps with many, that we lay such stress upon indulgences, which are apparently of but recent usage in the Church, not being found among Christians till a very late date. I answer, that it is not clear from whom the tradition of them originated. They are said not to be without precedent among the Romans from the most ancient times; as may be understood from the numerous stations in that city. Moreover [Pope] Gregory I is said to have granted some in his own time. We all indeed are aware, that by means of the acumen of later times many things both from the Gospels and the other Scriptures are now more clearly developed and more exactly understood than they once were; whether it was that the ice was not yet broken by the ancients, and their times were unequal to the task of accurately sounding the open sea of Scripture, or that it will ever be possible in so extensive a field, let the reapers be ever so skilful, to glean somewhat after them. For there are even now a great number of obscure passages in the Gospel, which I doubt not posterity will understand much better. Why should we despair of it when the Gospel is given for this very purpose, to be understood thoroughly and exactly? Seeing then that the love of Christ towards His Church continues not less strong now than before, nor His power less, and that the Holy Ghost is her perpetual guardian and restorer, whose gifts flow into her as unceasingly and abundantly as from the beginning, who can question that the minds of posterity will be enlightened unto the clear knowledge of those things which remain still unknown in the Gospel?[4]

St Vincent of Lerins on development

Newman had read in the classic text Commonitorium of the Gallic monk, St Vincent of Lerins (the Lérins Islands, off France), who died about A.D. 445, the beginning of his own theory of development:

Perhaps someone may ask: ‘So is there to be no development (profectus) of religion in the Church of Christ?’ Certainly, there is to be, and on the largest scale. Who can be so envious of men, so hateful towards God, as to try to prevent it? But it must truly be development of the faith, not alteration (permutatio). Development means that each thing expands to be itself, while alteration means that a thing is transformed from one thing into another.

Let, then, the understanding, knowledge, and wisdom of each and all, of individuals and of the whole Church, in all ages and all times, increase and develop (proficiat) in abundance and vigour; but only in its own kind, that is to say, in one and the same doctrine, the same meaning, and the same judgment (in eodem scilicet dogmate, eodem sensu, eademque sententia).

The religion of souls should follow the law of growth of bodies, which, though they develop and unfold their component parts with the passing of the years, always remain what they were. There is a great difference between the flower of childhood and the maturity of old-age, but those who become old are the very same people who were once young. Though the condition and appearance of one and the same human being may change, it is one and the same nature, one and the same person.

An infant’s limbs are tiny, a young man’s large, yet these two are the same. Adults have the same number of limbs as children have; and if there be any to which maturer age has given birth these were already present in embryo, so that nothing new is produced in them when old which was not already latent in childhood.

This, then, is undoubtedly the true and legitimate rule of progress, the established and wonderful order of growth: that mature age always brings to completion in the man those parts and forms which the wisdom of the Creator fashioned beforehand in the infant. Whereas, if the human form were to change into some shape not belonging to its own kind, or at any rate, if the number of its limbs were increased or diminished, the result would necessarily be that the whole body would become either a wreck or a monster, or, at the least, enfeebled.

So also the dogma of the Christian Religion should properly follow these laws of development, so as to be consolidated over the years, enlarged over time, refined by age, and yet continue incorrupt and unadulterated, complete and perfect in all the measurement of its parts and in all its proper members and senses, so to speak, admitting no change, no waste of its distinctive property, sustaining no variation in its limits.

For example, our fathers of old sowed the seeds of the wheat of faith in the field of the Church. It would be very wrong and incongruous if we, their descendants, instead of the genuine wheat of truth, were to reap the poisonous error of weeds. On the contrary, it is right and logical that there should be no discrepancy between the first and the last, and that from the increase of the wheat of instruction, we should reap wheat also, the fruit of dogma. And so, when in course of time any of the original seed is developed, and now flourishes under cultivation, no change, however, may ensue in the character of the plant. Granted that shape, form and variation have been added, still, the nature of each kind must remain the same. …

For it is right that those ancient doctrines of heavenly philosophy should, in the course of time, be tended, smoothed, polished; but it is unlawful that they should be changed, unlawful that they should be maimed, that they be mutilated. They may receive proof, illustration, definiteness; but it is necessary that they retain withal their completeness, their integrity, their properties.[5]

A portion of this is quoted in the Essay,[6] and in the Roman Breviary (Friday of Week 27 in Ordinary Time). Some important things are to be noted in Vincent: the notion of development joined to concepts that Newman would call ‘preservation of its type,’ ‘anticipation of its future,’ and ‘conservative action on its past;’ also the necessity to retain sameness of meaning; and the distinction of developments from alterations.

Newman’s continued interest in development

The notion of development never left Newman, and it re-appeared in letters and sermons, right up to the time of his writing the Essay. On 2 February 1843, Newman delivered the last of his University Sermons, The Theory of Developments in Religious Doctrine, anticipating in many ways the Essay he was soon to begin. It was published that same month in his book of Sermons … Preached before the University of Oxford. He opens by citing the text of the day for the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin Mary:

“His mother kept all these sayings in her heart.” … Thus St Mary is our pattern of Faith, both in the reception and in the study of Divine Truth. She does not think it enough to accept, she dwells upon it; not enough to possess, she uses it; not enough to assent, she develops it; not enough to submit the Reason, she reasons upon it; not indeed reasoning first, and believing afterwards, with Zacharias, yet first believing without reasoning, next from love and reverence, reasoning after believing. And thus she symbolizes to us, not only the faith of the unlearned, but of the doctors of the Church also, who have to investigate, and weigh, and define, as well as to profess the Gospel; to draw the line between truth and heresy; to anticipate or remedy the various aberrations of wrong reason; to combat pride and recklessness with their own arms; and thus to triumph over the sophist and the innovator. …

All subject-matters admit of true theories and false, and the false are no prejudice to the true. Why should this class of ideas be different from all other? Principles of philosophy, physics, ethics, politics, taste, admit both of implicit reception and explicit statement; why should not the ideas, which are the secret life of the Christian, be recognized also as fixed and definite in themselves, and as capable of scientific analysis? Why should not there be that real connexion between science and its subject-matter in religion, which exists in other departments of thought? …

Scripture, I say, begins a series of developments which it does not finish; that is to say, in other words, it is a mistake to look for every separate proposition of the Catholic doctrine in Scripture. This is plain from what has gone before. For instance, the Athanasian Creed professes to lay down the right faith, which we must hold on its most sacred subjects, in order to be saved. This must mean that there is one view concerning the Holy Trinity, or concerning the Incarnation, which is true, and distinct from all others; one definite, consistent, entire view, which cannot be mistaken, not contained in any certain number of propositions, but held as a view by the believing mind, and not held, but denied by Arians, Sabellians, Tritheists, Nestorians, Monophysites, Socinians, and other heretics. That idea is not enlarged, if propositions are added, nor impaired if they are withdrawn: if they are added, this is with a view of conveying that one integral view, not of amplifying it. That view does not depend on such propositions: it does not consist in them; they are but specimens and indications of it. And they may be multiplied without limit.

In the Essay, he quotes another portion of this 1843 sermon.[7]

In his Apologia Pro Vita Sua, Newman writes:

So, at the end of 1844, I came to the resolution of writing an Essay on Doctrinal Development; and then, if, at the end of it, my convictions in favour of the Roman Church were not weaker, of taking the necessary steps for admission into her fold. …

I had begun my Essay on the Development of Doctrine in the beginning of 1845, and I was hard at it all through the year till October. As I advanced, my difficulties so cleared away that I ceased to speak of “the Roman Catholics,” and boldly called them Catholics. Before I got to the end, I resolved to be received, and the book remains in the state in which it was then, unfinished.[8]

In late September 1845, Newman sent the Essay on Development to the press, just as it stood, coming to a sudden halt in its final chapter. The ‘Advertisement’ by Newman at the start of the first edition is dated 6 October 1845, three days before he entered the Catholic Church. He stopped writing it when he decided to become a Catholic, because the purpose of its writing was to answer the question that had plagued his mind for years: are the Catholic Church’s apparent alterations in doctrine and forms such as to nullify its claim to be the true Church of God bearing the revelation of Christ? Or are they legitimate developments that do not betray the original substance and message?

The Essay’s seven notes of a true development

The major originality in Newman’s theory is the identification of seven “tests” or “notes” of a genuine development. He called them “tests” in the 1845 edition but “notes” in the 1878 edition (while still using the word “test” 17 times in passing). A “test” can answer a question looking for a Yes or No answer, but a “note” is that by which something is known, and can therefore be a richer notion, when different pieces of evidence converge.

Taking this analogy as a guide, I venture to set down seven Notes of varying cogency, independence and applicability, to discriminate healthy developments of an idea from its state of corruption and decay, as follows:—There is no corruption if it retains one and the same type, the same principles, the same organization; if its beginnings anticipate its subsequent phases, and its later phenomena protect and subserve its earlier; if it has a power of assimilation and revival, and a vigorous action from first to last.[9]

These seven are then set forth in the following order in the Essay:

- Preservation of type

- Continuity of its principles

- Its power of assimilation

- Its logical sequence

- Anticipation of its future

- Conservative action upon its past

- Its chronic vigour

It is a singular achievement of Newman’s Essay that no one has added an eighth note to the seven that he gives. No one has been able to demonstrate that any of the seven is mistaken; no one has been able to refute the central ideas. The controversies around the Essay have all centred on this or that particular example Newman gives in applying the seven notes.

The third note, “power of assimilation,” he initially called the “power of assimilation and revival” (quoted just above); but “a power of revival” is not in the Essay a note of true development, but a note of Catholicity in general, mentioned only once again, in this well-known passage, at the end of the application of the seventh note, “chronic vigour”:

It is true, there have been seasons when, from the operation of external or internal causes, the Church has been thrown into what was almost a state of deliquium [eclipse]; but her wonderful revivals, while the world was triumphing over her, is a further evidence of the absence of corruption in the system of doctrine and worship into which she has developed. If corruption be an incipient disorganization, surely an abrupt and absolute recurrence to the former state of vigour, after an interval, is even less conceivable than a corruption that is permanent. Now this is the case with the revivals I speak of. After violent exertion men are exhausted and fall asleep; they awake the same as before, refreshed by the temporary cessation of their activity; and such has been the slumber and such the restoration of the Church. She pauses in her course, and almost suspends her functions; she rises again, and she is herself once more; all things are in their place and ready for action. Doctrine is where it was, and usage, and precedence, and principle, and policy; there may be changes, but they are consolidations or adaptations; all is unequivocal and determinate, with an identity which there is no disputing. Indeed it is one of the most popular charges against the Catholic Church at this very time, that she is “incorrigible;”—change she cannot, if we listen to St. Athanasius or St. Leo; change she never will, if we believe the controversialist or alarmist of the present day.[10]

Development has been compared to the enlargement of a picture, or the sharpening of the focus of a film projected onto a screen. The details are not newly added, but the magnification or clarification makes them discernible and easier to identify and examine. To continue with the same analogy: if one part of a picture is enlarged beyond its due proportion, and in isolation from the rest of the picture, then the vision of the whole is distorted or obscured, or even lost. So it is with movements that isolate truths, turn them into heresies, and can no longer be assimilated into, or co-exist with, the body corporate. Newman had said in his last University Sermon, cited above, that it is “almost a definition of heresy, that it fastens on some one statement as if the whole truth, to the denial of all others, and as the basis of a new faith”.

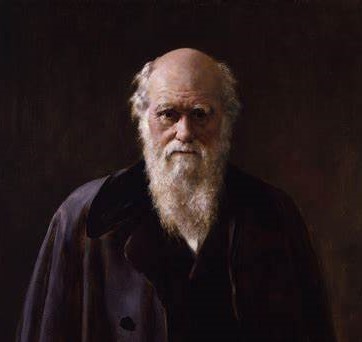

Newman, development, and Darwinian evolution

Some writers have seen a parallel between John Henry Newman’s theory of development (1845) and Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution (1859). It is said of these contemporaries of 19th century England, that what Darwin proposed of living species, Newman outlined of ideas. One recent promotion of the Essay says, “it traces how early Christianity developed into Catholicism and has been described as doing for theology what Darwin did for biology.” Superficially, it is easy to compare Newman’s theory to Darwin’s, and call it “the evolution of Christian doctrine.” Yet, apart from the fact that Newman’s Essay preceded Darwin’s Origin of Species by fourteen years, the truth is that the two theories tend in opposite directions and treat of different orders of being: Darwin of changing species in the biological order, Newman of consistent ideas in the intellectual, human and religious order. In Darwin’s theory, living beings evolve and take on new forms, new organs and new characteristics, and are transformed into higher and novel forms of life, becoming entirely new genera and species, adding to the variety of creatures in nature. In Newman’s theory of the development of Christian doctrine, there is never a transformation of one thing into another—this is precisely what he calls a false development, a corruption, an error, or a perversion of the original idea, when it does not remain itself. But if we want to use a biological analogy: ‘development’ is like the way a mustard seed grows into a mustard tree (the Synoptic Gospels’ analogy), or an acorn into an oak—all the hidden potentialities coming to explicit and visible fruition. ‘Alteration’ occurs if an oak tree becomes an orange tree, or evolves into an animal. Says Newman, speaking of ‘preservation of type’: “The adult animal has the same make, as it had on its birth; young birds do not grow into fishes …”.[11]

In Newman, the crucial thing in developments in Christian doctrine is consistency, remaining true to the original type—hence, not losing identity, not becoming something new without precedent or different in essence. Not that Newman spoke against Darwin’s theory; biology was not his domain, and he never meant that his theory of development of Christian doctrine had any application to physical science. He specifically states, early on, that corruptions and developments mathematical, physical and material are not in consideration here,[12] but only Christian developments of five kinds: political, logical, historical, ethical (moral) and metaphysical.[13]

As to Christianity, supposing the truths of which it consists to admit of development, that development will be one or other of the last five kinds. Taking the Incarnation as its central doctrine, the Episcopate, as taught by St. Ignatius, will be an instance of political development, the Theotokos of logical, the determination of the date of our Lord’s birth of historical, the Holy Eucharist of moral, and the Athanasian Creed of metaphysical.[14]

Vatican I and II on development

Vatican Council I was the first General Council to speak of the development of doctrine. It says dogmas must be understood “according to the mind of the Church” and then cites a sentence of Vincent of Lerins on that topic:

Hence also, that meaning of the sacred dogmas is perpetually to be retained which our holy mother the Church has once declared; nor is that meaning ever to be departed from, under the pretence or pretext of a deeper comprehension of them. ‘Let, then, the understanding, knowledge, and wisdom of each and all, of individuals and of the whole Church, in all ages and all times, increase and develop (proficiat) in abundance and vigour; but only in its own kind, that is to say, in one and the same doctrine, the same meaning, and the same judgment.’[15]

Vatican Council II spoke on the development of doctrine in its Decree on Revelation:

This Tradition which comes from the Apostles develops (proficit) in the Church with the assistance of the Holy Spirit, for there is a growth in the understanding of both the realities and the words handed down: through the contemplation and study made by believers, who treasure these things in their hearts (cf. Lk 2:19, 51); through a penetrating understanding of the spiritual realities which they experience; and through the preaching of those who have received through episcopal succession the sure charism of truth. For, as the centuries roll on, the Church constantly moves forward toward the fulness of divine truth until the words of God are fulfilled in her.” (Dei Verbum, 8).

In the light of Vincent of Lerins and of Newman’s Essay, this is quite a weak and uninformative passage.

Editions of the Essay

The text everyone reads today is that of Newman’s revised edition of 1878. As Newman says in his preface, he re-arranged the two parts of the edition of 1845 (Part I became Part II, and vice-versa) and made some alterations to the text but no changes to the argument as such.

If anyone wants to read Newman’s Essay, the Gracewing (U.K.) edition of 2018, edited by Fr. James Tolhurst, is the one to read. No other editions come near it for helpfulness. In addition to an illuminating introduction, Dr. Tolhurst provides, for the modern reader, comprehensive footnotes and explanations of the myriad Biblical, Patristic, theological, historical and literary references in Newman’s text, and an English translation of all Latin, Greek, French and Italian phrases and sentences. That edition is a perfect gift for any seminarian or student of theology.

There is great profit to be had by reading the Essay from start to finish. One learns in this historical survey of theology the crucial necessity of true developments in the Catholic religion as opposed to corruptions; consistency as opposed to perversion; truth as opposed to error and falsehood; permanence as opposed to innovation; – and seven comprehensive notes by which to identify them. Where the phrase “development of doctrine” is invoked today, Newman’s work enables us to see if it is used in a true or false sense.

[1] Chapter II, section 1

[2] Chapter II, section 5

[3] Foreword to Apologia pro Vita Sua, Loyola University Press, Chicago 1930

[4] Newman’s translation of the original Latin of Fisher’s Assertionis Lutheranae Confutatio [‘Rebuttal of Luther’s Defence’, 1st ed., Michiel Hillen van Hoochstraten, Antwerp 1523], Article 18.

[5] Commonitorium peregrini adversus hæreticos (‘Commonitorium of the pilgrim against the heretics’), ch. 23 (A.D. 434). ‘Commonitorium’ means aide-memoire, notes written to help memory. The theme of the work is what must be remembered to distinguish the Catholic faith from heresies and corruptions.

[6] In chapter V, section 1, no. 1.

[7] In chapter I, section 2, no. 9.

[8] Apologia, chapter IV

[9] Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, ch. V, no. 4

[10] Essay, ch. XII, no. 9 (second-last paragraph of the book)

[11] Essay, ch. V, section 1, no. 1.

[12] Essay, ch. I, section 2, no. 1.

[13] Essay, ch. I, section 2, nos. 2-9

[14] Essay, ch. I, section 2, no. 10. By “moral” as applied to the Holy Eucharist, Newman means the development of the attitude of adoration towards it.

[15] Chapter 4 of Dei Filius, Constitution on the Catholic Faith (1870), citing at the end Commonitorium, ch. 23, quoted above.