“Tis the times’ plague, when madmen lead the blind.”

William Shakespeare, King Lear

Introduction

Where does one look in order to find the Tradition of the Church? And for what does one look when he goes looking for it? Are we looking for doctrines- the res tradita; or are we looking for its mode of communication- the actio tradentis. Is Tradition captured by the distinction between the written word and oral teaching? Is Tradition a rule of faith? Or a source of doctrine? Is it synonymous with Divine Revelation? How do we distinguish it from the Magisterium of the Church? We know that Tradition runs through all of them, but is identical to none of them.

The principal question with which this series has dealt is: what is Catholic Tradition? The answer seems obvious, until we are asked to define it. Tradition, like culture, is something everybody knows and understands until the moment comes when he has to explain it. Then the blank stares and the awkward pauses begin to emerge. The problem with Tradition, like that of the culture, is that it is very easy to point to things. When asked to explain the Church’s tradition I can point to doctrines like the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption. I can also point to no meat on Friday, ember days and the Church’s liturgical calendar. All these things have something in common from our point of view: they are all ancient. They are not all equally ancient, but they predate all of us by several centuries; and in some cases, millennia. But herein lies the problem- even though they are ancient to us, they were not always ancient. But they were always, right from their first moment, part of the Church’s Tradition. So even though antiquity is an accidental[1] of the tradition- it cannot be what defines the Tradition.

The other thing people point to when trying to define the tradition of the Church is that it is something oral- it has not been written down. Although not untrue, if that idea is left unexplored, it creates a kind of artificial binary that became a point of contention during the protestant reformation; that in itself makes no sense. At least not from strictly logical and temporal analysis. All Christian teaching, all revelation, all doctrine was originally and irrefutably oral. The Lord preached first the Kingdom of Heaven and all the truths revealed in its coming- and this He only did by word of mouth (cf Matthew 4:17; 23; Mark 1:14-15). Long before there was anything written down, there was only an oral transmission of all that He had taught them (cf Mt 28:20). This from everything we know and all the historical evidence available to us is undeniable. The question then becomes; what are we to make of it? And what does it add, if anything, to our understanding of Catholic Tradition?

Sacred Scripture, although the written Word of God; its existence, writing and formulation is a work of an unwritten teaching. Scripture is the written word of God that emerges from an unwritten tradition. The fact that Christians wrote the scriptures is not itself the fruit of any written instruction. In fact, from everything that we know, it appears to be the fruit of no direct instruction at all. There is no commandment of which we are aware, either written or oral, to capture in writing the New Covenant. There is also no written list of which books it should contain or the authors who should write them. And the very teachings that were committed to writing in Scripture were themselves the oral teaching handed down from the Lord and the Apostles (cf John 21:24-25). Scripture is the written fruit of an unwritten tradition. That is why we spent the first three lessons examining the history of Scripture as a work of the Tradition. To define the Tradition of the Church as that which is unwritten- is not untrue, it is just misleading if not properly understood. For it places a division between Scripture and Tradition that is a mere material distinction and not something essential. It provides no basis for a formal distinction between them. And thus, offers nothing substantial in order to define them. What is essential to the Tradition of the Church is that it is received wisdom handed down from the Lord Jesus Christ.

These questions about the nature of tradition are far from recent, even though they do become more urgent around the time of Luther’s polemics. From the time of the Council of Trent, theologians have tried to answer a question that had largely been left untouched in the patristic and scholastic eras: what is the relationship between Scripture, Tradition, authority and the magisterium? Without being able to give a detailed analysis, both the Fathers and the Schoolmen all treated these aspects of the Church’s life as participating in the one authority of Christ. There was an organic link between them as they all expressed a unique manifestation of the one authority contained within the one body. It is perhaps a little difficult for us ‘moderns’ to appreciate the natural unity that the generations before us presumed. They did not see in Scripture, Tradition, the magisterium or the Church multiple authorities; as though they should be pitted or judged against each other. They saw different manifestations of the One Authority- Christ Himself. Although there were a few theologians from that period and earlier who raised these questions, none proposed a final answer. These questions will be debated intensely during the Council of Trent[2] and beyond. They will be stirred up again during the First Vatican Council[3] and will reach a fever point at the time of Humani generis[4] and Munificentissiums Deus.[5] However, none of this is an answer to the question: what is Tradition and how does it relate to the rest of Catholicism? This is the question we will continue to answer in this month’s lesson.

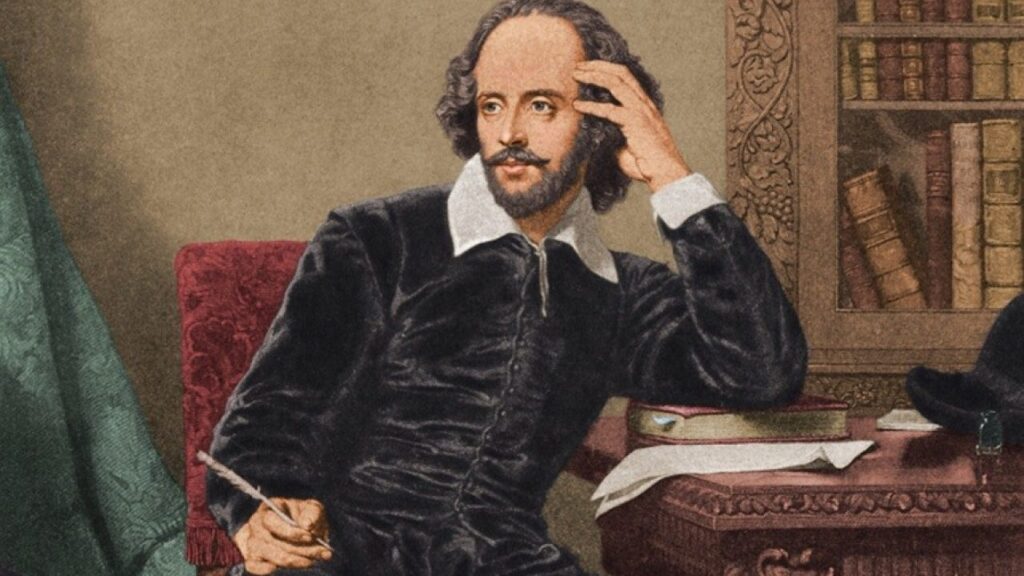

Shakespearean Tradition

King Lear is the greatest single work of the human imagination- it is Shakespeare’s greatest play. It is to literature what the Sistine Chapel is to painting and Bach’s Passion of St Matthew is to music. They say you should not meet your heroes, but you must definitely visit the Sistine Chapel, listen to Bach and see King Lear. There are many things in life that disappoint. King Lear is not one of those things.

In this month’s lesson, I am not going to ‘give you the meaning’ of King Lear. At the risk of sounding post-modern, there is no one single interpretation of King Lear. This is because Shakespeare is arguably the preeminent artist of all time. By that I mean there is more of human life- its humanity, its depravity and its greatness- packed into his plays, that they defy just one single interpretation. It is not because there is no such thing as truth- there is a superabundance of truth in his works that Shakespeare is inviting you to experience. In a way that parallels the Gospels- there is no one single way of reading them- but there are a host of ways to get them wrong. And I will endeavour not to get Kind Lear wrong.

One of the central ideas of King Lear is an examination of what happens to a world, a civilisation, when the next generation is ill equipped to take over from the current one. The play unfolds as the tragedy of a new generation which has not been formed to lead, guide and govern and instead is well schooled in the art of self and self-interest. But Shakespeare, like all great artists, is not content with just letting you see what happens when this kind of situation arises- a total tragedy- rather he wants to let you see how this state of affairs comes about and what causes it. He is not content with just showing you life- he wants you to feel, touch taste and know it (cf Psalm 34:8; 1John 1:1). He wants you to experience life from within life itself. And this is one of the reasons why I believe Shakespeare was a Catholic. I will have more to say about that in due course.

Many critics and scholars argue that Kink Lear is a nihilistic tragedy that represents Shakespeare’s despair and inner anguish. Others argue that it is a good bit of PR for a monarchy that was in a transitional decline. The Elizabethan period had ended and the question of what would come next weighed upon the country. Shakespeare was towards the end of his relatively short life by the time he published King Lear. Its first known performance was on St Stephen’s Day in 1606. As many of the historical details of Shakespeare’s life are unknown to us; and as his works are extremely complex, it is hard to always know what Shakespeare himself is thinking. It is easy to imagine that many ideas that he puts upon the lips and souls of his characters are merely a representation of life as Shakespeare experienced it, not necessarily how he lived it. I think to make too much of Shakespeare from Shakespeare is our modern temptation to psychologise everything. This statement, if I am to be consistent with it, will make arguing that he is a Catholic and this reveals something of the nature of Catholic Tradition, all the more difficult.

A Tale of Two Lears

For anyone unfamiliar with Lear, the play is set in ancient, almost mythical, pre-Christian Britain. Its actual time is not important to the play- but its lack of a specific time is meaningful. Lear opens with the King proclaiming how he is to divide his kingdom now that he is four score and upward (over 80) and he has no male heir. However, he has three daughters of whom he is very fond; with his youngest Cordelia, being his favourite. He devises a plan with his trusted advisors to divide his kingdom evenly between them and retire. The plan is approved by all and appears like a good one because of its even handedness. Lear, like all men, has his favourites, but he is not swayed by his own preferences as puts the peace of the kingdom above all, including his own natural affections. The first time we meet Lear he is a king in control of a kingdom that is at peace with itself and with the kingdoms surrounding it. There is no other Shakespearean play that has the king at peace with himself and with the world. Hence the importance of there being no specific time in this mythical age of peace. But this first plan to divide the kingdom, although not without its issues, is not the actual plan which brings him undone.

Before however this plan is to be put into practice, Lear adds a detail that he had not discussed with his advisors: he asks his daughters to pledge their love for him. Before he hands over the keys to the kingdom, in a scene reminiscent of John’s Gospel between the risen Lord and Peter the apostle (John 21:15-17), Lear asks his daughters three times: do you love me? The scene in Lear although possessing an echo of the Gospel story, is anything but that story. For Lear is not seeking love for the sake of the good of other, but for a political purpose. He asks his daughters to declare their love for him, something that no doubt he holds dear to his heart, but he does so in service of a deception. By getting them first to pledge their love, he is binding them to his plan of succession that he has not yet revealed to them. If they love him then they certainly cannot oppose him. The two eldest daughters Goneril and Regan- the unscrupulous ones- flatter Lear with words of love. They say what they need him to hear in order to obtain from him the things they want. Cordelia, his youngest, after hearing their false words pledges her love as sincerely as any daughter should. But she refuses to conflate love with opportunity. She will only speak the truth, not falsity in the service of flattery. The king becomes enraged by this and disinherits and disowns her immediately and publicly. He then divides his kingdom between his two eldest daughters- Goneril and Regan. It would appear that flattery may be falsity, but it is effective; especially on the vain. After this outburst from the king, the Earl of Kent confronts and berates Lear publicly for his ill-considered actions and abandoning his original plan. Lear, not being able to backdown and not wanting to hear the truth, banishes Kent too from his kingdom. And once the truth has been banished, the stage is set for what will be an inevitable tragedy.

The fact that there are two plans to divide Lear’s kingdom- the even handed and the vengeful- is missed on most literary critics.[6] The problem of Lear is the problem of kings: how does one ensure succession? In Shakespeare’s mind, it is easier to establish a kingdom than it is to hand it on. It is easier to build cultural and political institutions than to preserve them for posterity. How does a king, once something of great value has been established, maintain what he has built? How does one hand on the treasure he has received? The problem of Lear is the problem of kings- which is the problem of tradition.

Culture and Tradition: at the crossroads

This Journal is dedicated to the exploration of the relationship between culture and tradition: what role does culture play in the communication of tradition? And how does tradition form and shape the culture? It is clear that the two are linked, both within human society and the Church. The Church is always at Her strongest when She is living more fully into the riches of Her Tradition. And this strength is always made manifest when she is creating great works of culture. As she was purifying and elevating the glories of Greek philosophy- She was building Gothic cathedrals and medieval Christendom. As She was rebuffing the errors of Protestantism, She was creating the glories of the Baroque. Whenever the Church moves forward it is because she is always reaching back- not to what is behind Her, as though She could dig up her traditions, but reaching back in order to embrace Her eternal present. Culture and tradition are clearly related- the question is: how? And just as importantly: why?

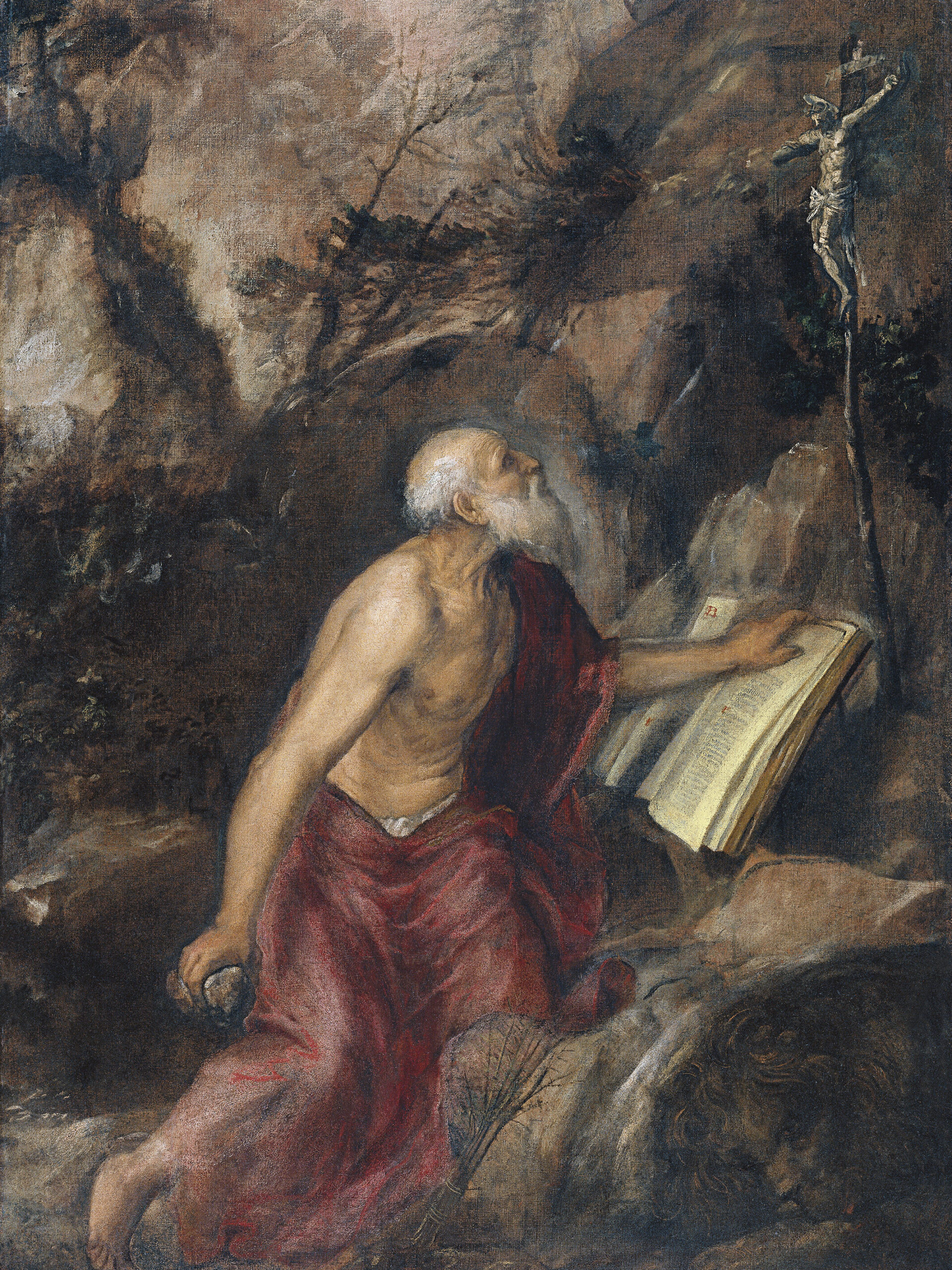

From within the tragedy of King Lear emerges a theme: do culture and its civilisation matter? The play asks the question: if you reduce man to his barest essentials do you then discover the true essence of man? Edmund, the bastard son of Gloucester wants to make nature his goddess, thus despoiling man of culture and therefore stripping humanity from the human heart. As an illegitimate son, he cannot accept that culture and convention make him less an heir, when nature alone makes him no less a man. Edgar, his legitimate brother will inherit a kingdom simply because of custom and not because of ‘natural’ difference between them. As the play descends into tragedy, and the king tumbles into madness, the question is asked: is man no more than this? (Act III scene 4). In the most important scene in the play, which is the play’s moral centre, when Lear is on the heath, stripped naked of all his kingly robes he begins to command the storm not to be. He is no longer in his kingly finery; he is alone in nature and thus not only less a king than he once was, but also less a man. It is in that moment; Lear begins to pray.

Culture as fiction

The particular error that Shakespeare puts on Edmund’s heart is not based entirely on a lie, for culture is indeed an artifice. It is a kind of ‘pretence’ that must replace what has been stripped away- not just a loss just of nature but of grace. Culture is an attempt to restore materially what in truth was an immaterial loss. Culture is thus a kind of mediation between the inner world of man and the outer world around him. It must restore to our nature the very thing against which our nature rebelled in the garden: the harmony of man. Thus, if culture is a mediator, then it is necessarily a third thing. And because it is a third thing, it is something both like and unlike the opposites between which it mediates. As Aquinas teaches that the body mediates the soul to the self, thus does culture mediate the inner world of man to the outer world around him. It is a manifestation of the imaginary that must restore the very thing that man most craves: peace with the world, peace within himself and above all- peace with God. That is why culture is a kind of fiction- but the most important kind of fiction of all, for it represents a reality that we have lost, and spend all our waking hours desperately trying to recover. That is why man can be critical of his need for culture and even disdainful of it; and why a ‘naturalist man’ like Edmund can dismiss it. For it is unlike the two realities that we know- our inner and outer worlds- and therefore can seem like an intruder. But culture is not like plastic flowers in a botanical garden, it is rather dry land to the drowning- the one sure thing that safeguards our reality.

But what makes King Lear a tragedy? The tragedy of Lear is the tragedy of deception. But it is a particular kind of deception- the most ancient kind of all. The fall of Lear is the fall of man- and that is the deception between a man and a woman. When this relationship is damaged the world falters. Lear wants to deceive his daughters for a political end and his two daughters want to deceive their father for material gain. Throughout the play, the women lack femininity and the men lack virtue. The tragedy of Lear is the tragedy of The Fall.

But how does culture restore; and what role does tradition play in this restoration? If culture is a kind of artifice- because it mediates between two realities- it can be ignored or even discarded. For culture itself is indeed something natural to man- but not entirely natural to all of him. For in our sin, we fractured that relationship between our inner world and the outer world around us: I was naked… I was afraid… and I hid myself (Gen 3:10) But what man lost most was not just a naturalistic paradise- he lost his friendship with God. Man no longer walked with God, and God no longer walks in his garden. Culture alone, unaided by the very thing that we lost- intimacy with God- is unable to restore the one thing that we crave. That is why all human cultures all throughout human history are unable to restore the thing man needs most- friendship with God. Even the Jewish culture- with all its rituals and sacrifices, its purity laws and prayers- was unable to restore the very thing that it prefigured. For that to actually happen, more than just the inner world of man had to be mediated to the outer world around him- something of the divine had to be mediated to all of creation. And that required not just God being close to us- He had to become one like us. And this likeness- the greatest of all treasures- had to be mediated to all mankind throughout all mankind’s history. And this is the role of Tradition- not just to hand on the keys to the kingdom- but the very Kingdom itself.

But how can culture restore what grace alone can only do? Peace of soul. Peace with the world. And above all things- peace with God. We want to get back what we lost. That is why we strive and struggle. It is why we plant gardens and tell stories. We have some kind of ‘natural memory’ of what was lost- but we have no way of restoring it by ourselves. This is why the Lord God must make coats of skins, and clothe them (Gen 3:21). But if what is lost is to be restored then we must first re-learn to do the very thing that we ceased to do in the garden: walk once more in friendship with God: firstly, in the halakha of the Old Testament but most importantly in the Tradition of the New. Only a culture that is the fruit of Tradition can mediate the eternal truths of God- His presence- to all of creation. Culture mediates the inner and outer worlds of man- Tradition mediates the world of God to all mankind and through mankind to the world. And this is why at the moral centre of King Lear, the King prays:

Poor naked wretches, whereso’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and windowed raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? Oh, I have ta’en

Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp.

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just.

The moral centre of King Lear is a prayer. But it is a Catholic prayer. Lear despairs of the fact that he did not pay more attention to provisioning for the poor: Oh, I have ta’en Too little care of this! But this is not just a cry to feed the needy (cf Mt 19:21; Luke 14:13-14)- it is a declaration that in order to restore poor naked wretches, one has to become one like them: to feel what wretches feel. That in the timeless time of King Lear, emerges a longing for the coming of Christ. But not just His coming in Bethlehem, but his timeless coming in the eternal present. The prayer of Lear is the prayer of one who knows that the actions of man, when elevated by a moral response to truth, reveal the glory of God: And show the heavens more just. That only man, when he acts according to custom- a culture enlivened by the Tradition- does man mediate the presence of God to the world. Nature is merely nature; and culture is merely culture unless we enliven it by a moral response to truth in order That thou mayst shake the superflux to them- which is revelation to the world that God alone is good. Lear clearly acknowledges the plight of the poor as they face the pitiless storm, but the seasons such as these to which he is referring in this prayer, is the moment in which Lear finds himself right now and without defence- deception had taken over his heart and now calamity has taken over his life. Lear is defenceless because he has been stripped of culture- naked upon the heath– and his culture has been stripped of tradition. And without a culture enlivened by Tradition, man is not even a beast, he is merely tragedy.

Conclusion

Tradition is a moral response to truth- it requires a moral life even more than it requires an intellectual one. Catholicism has always walked a tight line between what you must know and what you must do. Preferring a moral life to intellectual pursuits- but always elevating the intellectual life, without making it an idol of self-satisfaction and pride. What motivates Lear to seek deception from his daughters and not accept the truth from either Cordelia or Kent? Perhaps the fact that the peace of his kingdom, the very thing he is trying to preserve, is not built on the Rock. At the opening of the play, Lear is the most enviable of all of Shakespeare’s monarchs enjoying unprecedented peace. But peace without a culture enlivened by tradition cannot hold. A peace not built upon the rock is peace destined to fail (Mt 7:24-27; Luke 6:47-49; Mt 16:18). I do not wish to read too much into the opening scene when Lear wants to hand over the keys to his kingdom and requires a thrice declaration of love from his daughters. But it is curious that even in the world of Lear, long before the coming of Christ- where there is no rock there is no future. And in Shakespeare’s world, the Rock had been taken away.

It is impossible to prove that Shakespeare was a Catholic. He was baptised a protestant, likely married in a protestant ceremony and was buried in a protestant graveyard. But there are other features of his life that at least speak to a catholic sympathy. My point is not so much that we can prove that he was a card-carrying member of the Faith- but that his whole world and the world inside his own imaginary was deeply and irretrievably Catholic. Many say that he was not a religious writer, nothing could be further from the ruth. Everything Shakespeare did is full of religion- and much like the Catholicism I believe he treasured- not everything he wrote was in the form of a cross; but everything he wrote was informed by the Cross.

[1] An accident (Greek συμβεβηκός), in metaphysics and philosophy, is a property that the entity or substance has contingently, without which the substance can still retain its identity. An accident does not affect its essence, according to Aristotle. It does not mean an accident as used in common speech, a chance incident, normally harmful. Accident is contrasted with essence: a designation for the property or set of properties that make an entity or substance what it fundamentally is, and which it has by necessity, and without which it loses its identity.

[2] The Council of Trent (1545 and 1563) was the 19th ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. A response to the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the “most impressive embodiment of the ideals of the Counter-Reformation.” The Council issued key statements and clarifications of the Church’s doctrine and teachings, including scripture, the biblical canon, sacred tradition, original sin, justification, salvation, the sacraments, the Mass, and the veneration of saints and also issued condemnations of what it defined to be heresies committed by proponents of Protestantism. The Council met for twenty-five sessions between 13 December 1545 and 4 December 1563. Pope Paul III, who convoked the council, oversaw the first eight sessions (1545–1547), while the twelfth to sixteenth sessions (1551–52) were overseen by Pope Julius III and the seventeenth to twenty-fifth sessions (1562–63) by Pope Pius IV. More than three hundred years passed until the next ecumenical council, the First Vatican Council, was convened in 1869.

[3] The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican was the 20th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, held three centuries after the preceding Council of Trent which was adjourned in 1563. The council was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, under the rising threat of the Kingdom of Italy encroaching on the Papal States. It opened on 8 December 1869 and was adjourned on 20 September 1870 after the Italian Capture of Rome. Its best-known decision is its definition of papal infallibility. The council’s main purpose was to clarify Catholic doctrine in response to the rising influence of the modern philosophical trends of the 19th century. In the Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith (Dei Filius), the council condemned what it considered the errors of rationalism, anarchism, communism, socialism, liberalism, materialism, modernism, naturalism, pantheism, and secularism. Its other concern was the doctrine of the primacy (supremacy) and infallibility of the Bishop of Rome which it defined in the First Dogmatic Constitution on the Church of Christ (Pastor aeternus).

[4] Humani generis is a papal encyclical that Pope Pius XII promulgated on 12 August 1950, “concerning some false opinions threatening to undermine the foundations of Catholic Doctrine”. It primarily discussed, the encyclical says, “new opinions” which may “originate from a reprehensible desire of novelty” and their consequences on the Church.

[5] Munificentissimus Deus is an apostolic constitution published in 1950 by Pope Pius XII. It defines ex cathedra the dogma of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It was the first ex-cathedra infallible statement since the official ruling on papal infallibility was made at the First Vatican Council (1869–1870). In 1854 Pope Pius IX had made an infallible statement with Ineffabilis Deus on the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary, which was a basis for this dogma.

[6] Harry V. Jaffa, “The Limits of Politics: King Lear, Act I, Scene i,” in Shakespeare’s Politics, 113–45