Introduction

One of the overarching ideas in these lessons is that the Church’s Tradition emerges as both doctrine and culture. Which then begs the question: why does this matter? Surely what matters in religion- any religion- are its teachings. Why does it matter at all, let alone a great deal, that those teachings create a culture? Surely it matters that the truths of Christ are preached and the question of culture is best left to those with a talent for it. Against the backdrop of the Lord’s Great Commission to go and baptise all nations, culture seems like a minor matter. The Gospel never mentions Christianity’s cultural imperative; to either create its own culture or to transform the culture in which it finds itself. Even the Judaism from which Christianity emerged never made any attempt to proselytise or ‘evangelise’ foreign cultures. Mesopotamia was never taught to follow Jewish dietary laws and the Canaanites were never invited to observe Passover. The issue of culture can seem like a marginal question in the grand scheme of salvation; especially in the light of the Church’s first centuries of existence.

Yet, the sources from the period are quite clear: Christianity, although thought to be a minor breakaway Jewish sect, drew the attention of both the political authority and intellectuals. Non-Christian writers such as Tacitus[1], Suetonius[2] and Pliny the Younger[3] all reference Christianity to greater and lesser degrees and the persecutions it faced. First under Nero and then under successive Roman emperors. The evidence is clear that there was a political and cultural attempt to persecute Christianity out of existence. What is not so clear is why. The Romans and others saw Christianity as some kind of threat to their civilisation, religion and way of life. Subsequent western history would vindicate their fears. After all, how many Romans today burn incense to the gods? The question still remains: what threat did they see in a religion whose doctrines they didn’t understand?

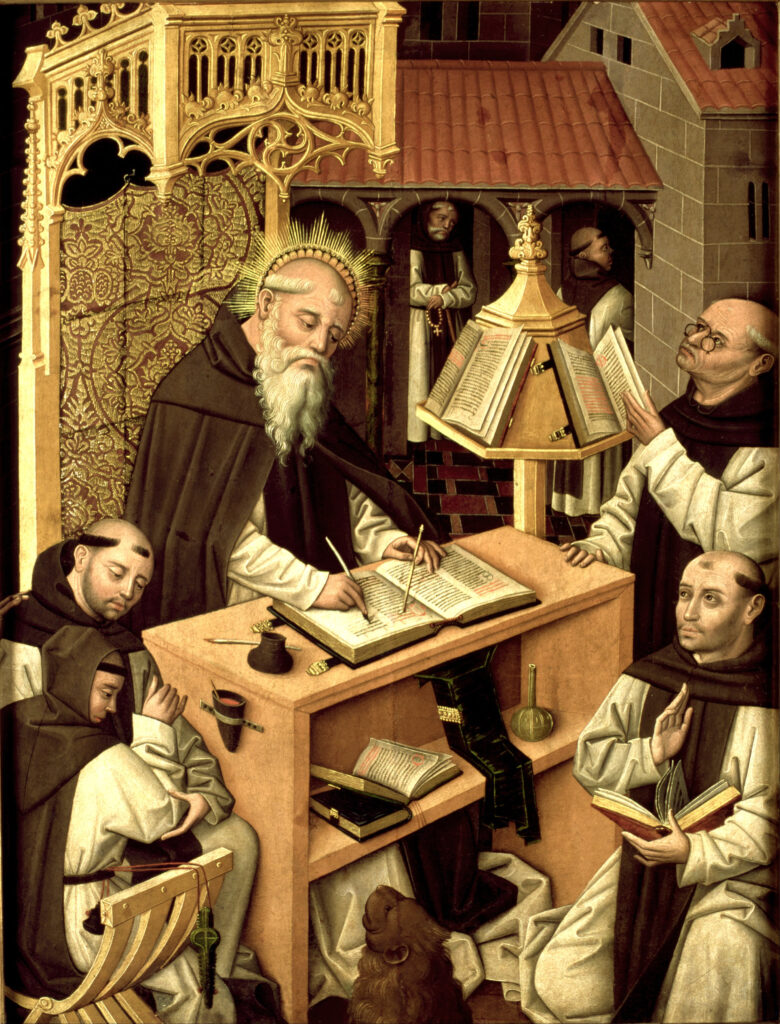

In our attempt at unpacking why Christianity emerges as a culture, one of the first questions we asked at the start of this series was why the Lord Himself never committed any of his teaching to writing. The only evidence we have of the Lord ever writing anything is in the Gospel of John (Jn 8:6-8); and even then, it is rather vague as to what, if any words, He actually wrote. St. Thomas Aquinas asked a similar question. The answer he gives, as only Thomas can give, goes straight to the heart of the matter: a teacher’s role is not only to teach by communicating a truth, it is essentially the role of forming a life. And as the Lord was the best of all teachers- His teaching must touch not only the intellect; it must also reach the heart:

I answer that, it was fitting that Christ should not commit His doctrine to writing. First, on account of His dignity: for the more excellent the teacher, the more excellent should be his manner of teaching. Consequently, it was fitting that Christ, as the most excellent of teachers, should adopt that manner of teaching whereby His doctrine is imprinted on the hearts of His hearers; wherefore it is written (Matthew 7:29) that “He was teaching them as one having power.” And so it was that among the Gentiles, Pythagoras and Socrates, who were teachers of great excellence, were unwilling to write anything. For writings are ordained, as to an end, unto the imprinting of doctrine in the hearts of the hearers.[4]

Although principally a work of grace, to teach the truths of Christ means to form a Christian mind. And for that to happen, that teaching must do the work of capturing the imaginary. Both the intellect and will must be transformed if the person is to live a Christian life. Christianity did not become the first truly ‘global phenomenon’ by asserting intellectual propositions in a logical manner. At the same time it was making clear what it believed, it was transforming lives, because Christianity was colonising the interior world. Christian Tradition emerges as a Christian culture precisely because it captures the imagination and transforms the interior life of the person in a way that the Roman senate and its forum could never do. Christianity indeed was a threat to the Coliseum that the emperors saw coming, but could not quite explain and certainly could not prevent. If Christianity had come armed with military might and a legal framework, it would have failed in its mission. Instead, Christian Tradition came with parables, stories, and new ideas that created a way of life not just for each individual Christian, but also for the entire civilisation and its culture.

From Generation unto Generation

St Thomas’s insight into Christ’s teaching underscores an element of the Christian Tradition that can easily be ignored: Tradition requires a community of persons. The transmission of tradition requires that both the giver and the receiver be in close proximity to each other; not only geographically- but also intellectually and morally too. Tradition only exists in the milieu of people writes the Yves Congar in his work The Meaning of Tradition. The Tradition of the Church means that it is inseparable from the act of one living person handing it on to another. And the origin of this transmission lies in the very person of Jesus Christ Himself. God is the origin of Tradition. And the Church is the community of persons inseparable from its communication from age to age. It is why the entirety of the Church’s Tradition belongs to the whole Church from generation to generation and cannot be outlawed or ignored; despite the efforts of many over the last several decades. Thus, the Church’s Tradition, although a doctrine, is not a doctrine exclusively.

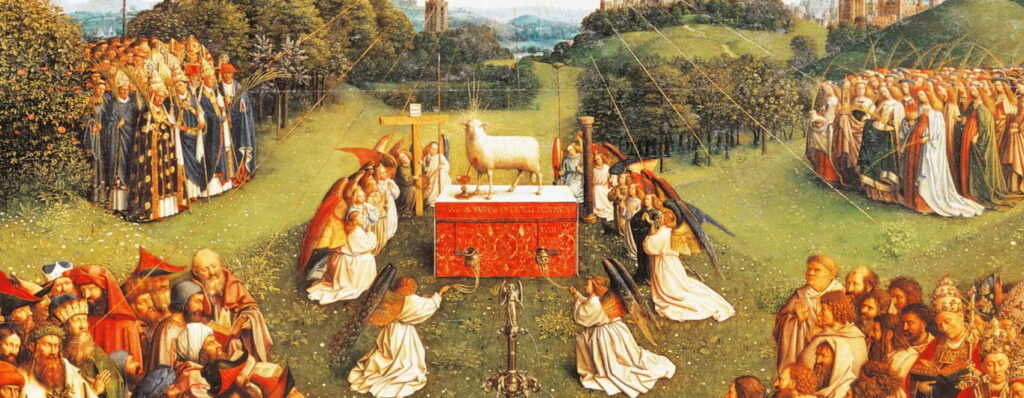

Catholic Tradition emerges in both doctrine and culture- but it does not emerge directly from doctrine into culture. Catholic culture does not emerge from Christian revelation without the mediation of the human person sanctified. Cultural institutions are created because there is a shared way of life that emerges from within the context of Divine Revelation. For at the heart of Christian life is the vocation to become like Christ (c.f. 1Cor 11: 1). And the soul, once elevated by grace lifts up whatever is around it (c.f. Romans 12: 20-21). At the heart of Christian culture is the human person remade in the image of Christ (c.f. Romans 8:29).

So, if this is the process that is embedded in Christian doctrine, why is contemporary Catholicism so bereft of Catholic culture? The answer lies in our abandonment of Tradition. The Christian religion emerges from within the tradition and cultural context of ancient Israel and its Jewish faith. And as we have said, St Paul was adamant that we cling to the tradition that has been handed to him and that he has handed to us- both written and oral (c.f. 2Thess 2:15). So, when did we come up with the bright idea that we could break with received wisdom and go at it on our own? This is what we will examine in this month’s lesson.

Middle Age Mayhem

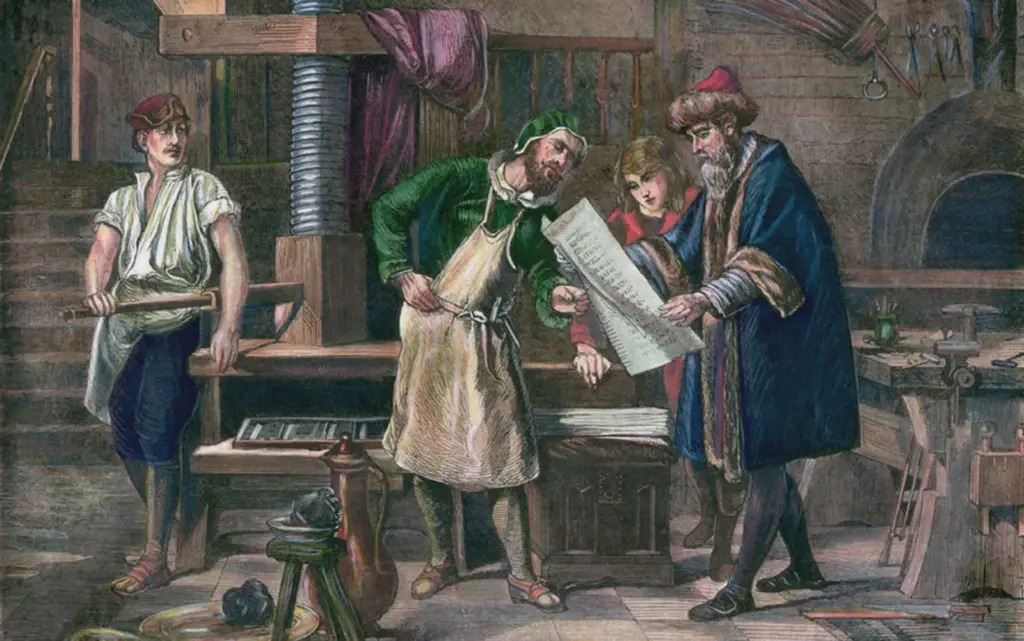

The answer is somewhat obvious to anyone with even the feintest understanding of Church history. The break with tradition was institutionalised in Wittenberg, Germany on October 31, 1517. But even that date, as ominous as it was for the future of Christianity and its culture, is not the entire origin of the problem. And it does not immediately shed light on why contemporary Catholicism is so bereft of both tradition and culture. As in all things, long before we have to deal with the fallout from bad actions, we have to endure the assault of bad ideas. Philosophy underpins the moral life. Thus, a bad moral turn is always preceded by and even more disastrous philosophical one.

The Middle Ages are a high point in Western Civilisation. So much of the work done by the Fathers of the Church culminated in the creation of one of the richest artistic, architectural and intellectual periods of human civilisation. As in all periods of history, it was not without its issues, especially during its later stages. This latter period, often referred to as the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages, was a series of social, political and religious events across Europe that undermined the achievements of the 11th and 12th centuries. The Great Famine of 1315-1317[5], the Black Death[6] and the Great Schism[7] are a few of the examples from the period. However, as traumatic as these events were, the actual makings of the Protestant revolt were not found in any of them particularly. The theological failure of Protestantism was an artefact of the philosophical decline that had emerged during that period. Where we pick up the strands of the Protestant error is in the intellectual failure that preceded the general collapse of the culture.

A Question of Universals

One of the most enduring debates in all of philosophy is over the question of universals. This may not sound like an obvious place to begin to examine the rise of Protestantism and the associated collapse of Christian tradition and culture- but there is no better place to start. The question of universals is a very intricate, and at times, complicated study. It is far beyond the nature of this lesson to address it in its entirety. Again, it is one of those studies that is well worth your time, but is probably beyond the interests of anyone who is not well trained in philosophy. Let me give you a summary of the question and why it is so important for our examination of Luther and Catholicism’s current cultural mess.

The question of universals can be restated as a study of how language captures reality, and whether language says anything meaningful about reality and our capacity to know it. Most of the confusion about the question comes from a want of understanding of the term ‘universal’. But even that, is not so difficult to grasp.

Human language is full of universal terms. The world is only full of particulars. That is, English, like all languages, has categories of things that are really terms for a collection of things. For example, we use the term “animal” to talk about cats, dogs and kangaroos. We use the term “man” or “humanity” to talk about Peter, Paul and Mary. Our language is full of such ‘universal’ terms. But the world is not full of such ‘universal’ things. The only things that exist in the world are my pet dog Scruffy and Skippy the bush kangaroo. Universal terms do not exist in nature. There is no such thing as ‘animal’ in the physical world. And you do not find ‘humanity’ walking down the street either. There are individual men and individual animals. So, why then does our language have so many universal terms? And why do we use them so often to describe things that don’t exist in the world? If we are just making up terms for things that don’t exist, why do we persist in using them if they don’t say anything meaningful about the world because they don’t describe anything that exists within it? This problem is one of the central problems in philosophy. It fascinated the ancients- Aristotle and Plato (Augustine too was part of the discussion). It fascinated medieval philosophers and it is still of great interest to us today. So, why?

Now, when I talk of the universal category ‘animal’ you know that I am not talking about anything prowling around in the jungle or in your backyard, rather I am talking about some very general category in which different types of animals belong. When I use the universal term ‘animal’ I am not picking out any particular animal, rather I am referring to a class of characteristics that all animals share. The question then becomes- what purpose does referring to such an existent class of non-existent things serve? This is where the question of universals becomes quite complicated and specialised. But let me give you a brief explanation of what it is and why it matters to us.

Clearly animals- all animals- share certain properties. For example, they live, they breathe and they do the things that animals do. That is true of dogs, cats and kangaroos, even if they are all different kinds of animals. The question is- where does this ‘class of properties’, i.e. the universal term (e.g. animal) exist? Does it just exist in our minds? Does it just exist in the words we use? Or does it only exist in the individual animals themselves? This is the heart of the philosophical problem of universals.

St Thomas Aquinas had a rather ingenious answer to this question. His basic understanding of a universal, is that it exists really in all three. When I use the term ‘animal’, the properties of animals (all of those properties common to all animals) exist in reality in the individual animal as its nature (natural kind), but also as a concept (mental image) in my intellect that is then captured in the word I use (through language). Although no such universal thing as ‘animal’ exists in nature- the properties of ‘animal’ exist in all those things that are animals according to their nature (kind). My knowledge of the concept ‘animal’ is a result of my intellect’s ability to abstract from the nature of each individual animal that I observe all those properties common to all animals I have observed. I notice that each individual dog, cat and kangaroo eats and breathes etc, thus the universal term ‘animal’ contains all those properties common to the nature of all animals. And from that abstraction the category ‘animal’ emerges. St Thomas theory is generally referred to a conceptualist-realist theory of universals.

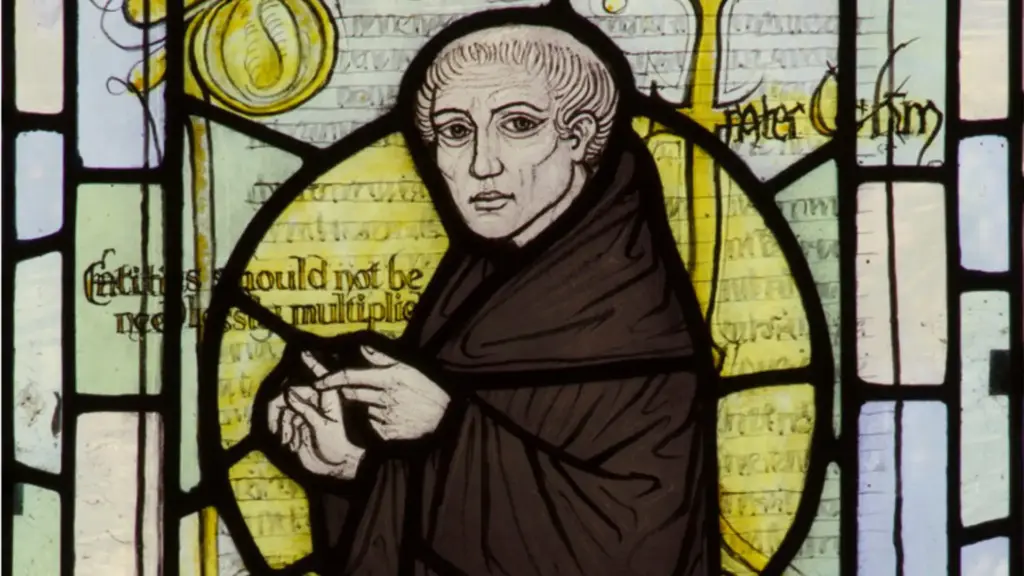

Now, for anyone with a reasonable philosophical background knows that I have simplified the discussion of universals almost to its breaking point. But in order to be brief, I trust I have not been misleading. It is still an ongoing debate in contemporary philosophy as to what universals really are, or if they are indeed real at all. Those of you without any particular philosophical training must be wondering: what has any of this got to do with the Protestant controversy and its heresy. For that we have to turn to a later medieval philosopher known as William of Ockham.[8]

Ockham’s Close Shave

Most people are familiar with Ockham’s razor.[9] What they don’t know is that he was one of the first philosophers who worked out a theory about universals called nominalism. To simplify without doing an injustice to Ockham’s theory, he posited that the universal names we use for things are merely ‘aggregators’ or ‘common terms’ that we use to describe individuals with common characteristics. The only place that the term ‘animal’ exists is in the concept or word ‘animal’. When I use the word ‘animal’ as a nominalist, I am picking out that individual thing with those characteristics common to the name ‘animal’. There is no nature inherent in that thing that defines it is as ‘animal’ or causes it to be ‘animal’; there is only my subjective experience of individual animals to which I give the name ‘animal’. The individual thing is ‘animal’ only in so far as I use that name to describe it. The origin of the term nominalism, comes from the Latin word nomen, meaning ‘name’.

Now, this possibly does not sound like something very important to Protestantism. You probably know a great many protestants who have never even heard of the term let alone subscribe to it as their religion. They are devoted to Scripture not to the names of things. It perhaps does not sound that interesting to you either, but in reality, it has a profound impact on what we say we can know about reality and what our Christian faith can say about itself.

Unjustifiable Justification

Nominalism, as a philosophical doctrine, presents a particular problem for Christianity. If universals such as ‘man’ and ‘animal’ do not actually exist, and only individuals exist, then there are no such things as natures (natural kinds). And if there are no such things as natures, this means that there are no real relations between things. If individual things do not share a common nature- then the only thing they can share is a common name. If there are no natures, only names, then the only thing that individual things ‘share’ between them is the individual who does the naming. Which is to say, they ‘share’ nothing at all, as the world is composed exclusively of individuals. As you may be able to guess already, this is going to undermine Christian theology and culture. Let me describe a few of the religious consequences of such a defective philosophical theory.

The first, and most obvious issue that arises, is that we now have a philosophical doctrine that underpins the moral error of individualism. If only individuals exist, and they exist without sharing any common nature, then only individuals matter and individualism becomes its own reward. Asides from the moral tragedy of the hyper-individualism playing out rather dramatically in our own modern culture, it also means that there can be no real relations between God and creation- between God and us.

The principal difference between protestant and catholic theology is in the doctrine of justification. This goes right to the heart of Christianity. At the heart of Lutheran theology is the idea that righteousness is imputed by God to the unrighteous person exclusively by the merits of Jesus Christ on the Cross (solus Christus); and that a person is saved exclusively by an act of faith in Christ (sola fidei). There is nothing that a person can do to merit this and no observance of the moral law can obtain this. Salvation is a free gift of God for His glory (soli Dei gloria) and whom He chooses to save is the prerogative of His exclusive will. Justification is not a fruit of any work on our behalf but is the sole work of grace (sola gratia)- it is a judicial declaration that a soul is now justified without there being any change in the nature of the soul.[10]

The principal point of departure between Protestantism and Catholicism is not the exclusivity of Christ, the need for grace or even the idea of justification by faith alone, but rather the real change that justification- the infusion of grace at baptism- makes in the nature of the soul. For Catholics, the infusion of supernatural (sanctifying) grace is a lifting up of our nature and the re-establishment of a new relationship in Christ (c.f. 2Peter 1:4). What is re-established at baptism is a real relationship with God through the sanctification of our nature through grace. For Catholicism, justification is infused and not imputed. ‘Righteousness’ is not simply a ‘name’ that God attributes to the soul externally, but a change in our nature so that we can be remade in the image of Him who made us, and through Him who redeemed us. In Protestantism salvation is a declaration; in Catholicism it is a transformation.

What’s in a Name?

The nominalists roots of protestant justification are clear:[11] ‘justified’ is merely a name God imputes to the soul whom He chooses. It is an act of God’s will alone made possible by the death of Christ on the Cross. And since there can be no real relationship between God and His creature (His creature having fallen into total depravity because of sin thus losing all likeness to its creator) a certain difficulty presents itself: how then does someone know that he is saved? This is really a two-part problem. The first, how does one know that salvation is actually a thing? And second, how does one know that he is counted among those saved?

The first part is answered rather easily in the Protestant doctrine of sola scriptura. The same God who wills my salvation is the same God who wills to reveal that salvation in His word. Just as the salvation offered to me is an act of God’s will imputing the justice of Christ crucified to me by covering over my sins; so too is His revelation of that salvation an act of His will recorded in Scripture. There is only one saviour who wills my salvation, therefore there is only one source of authority of that salvation- the Bible. Hence the protestant doctrine of sola scriptura.

The second part of the problem is somewhat trickier: how does one know he is saved? Protestantism’s answer is consistent with its nominalist and voluntarist[12] roots- just as God declares my salvation by ‘naming’ me as one of the saved, I know that I am saved when I declare that Jesus is my saviour. ‘Righteous’ becomes a name that God gives to the saved and ‘saved’ is a name I claim for myself when I declare Jesus as my personal Lord and Saviour. This is at the heart of why Luther’s Protestant doctrine is both nominalist (salvation in name only) and subjective (I declare my personal faith in Jesus). Protestantism is a perfectly consistent doctrine based on an entirely false premise. Given the above account of the Protestant doctrine of justification- how does this shed any light on contemporary Catholicism’s abandonment of tradition and its cultural distress?

Modern Catholicism’s Protestant Malaise

Tradition, Christian Tradition, is a kind of knowledge- but it is a particular kind of knowledge rooted in a moral response to revealed truth. The deposit of faith contains those truths revealed for our salvation. But salvation itself is the re-establishment of a real relationship between God and the person- not an imputed one. However, in order for there to be a real relationship between God and man, there must be something shared between them. And for this to be the case, there must be some connaturality between God and man. There must be something in the nature of man that is shared with the Divine. At our original creation we were made in the image and likeness of God; in our sin we lost the likeness but retained the image. Only through the merits of Christ crucified was that likeness, through grace, restored to us. This restoration in Christ, the justification we received, is a real relationship because it is the sharing of something in common- the image of God at creation and a likeness to Christ at redemption. This is the foundational difference between Catholic and Protestant theology.

The effect of such a difference between these two theologies plays out in how we understand and live into Tradition and the culture we create. In Catholic theology, Tradition is both the content and process of that real relationship established in Christ crucified. Tradition is both the revelation of the deposit of faith (content) and that process of handing that content on, which is the formation of both an intellectual and moral likeness to Christ: to have the mind of Christ in you (1Cor 2:16; Philippians 2:5). But this conformity to Christ must also be shared between believers (John 17:20-23; Romans 12:4-5; 1Cor 16:10). As we said at the start of this lesson, the transmission of the Tradition is inseparable from the community of persons charged with its reception. Thus, any altering of either the content or process of that relationship- an abonnement of Tradition- will necessarily distort the community of believers intimately associated with it. Luther’s protestant ideology did damage both to the content of our faith and to the structure of how we live it out. Nowhere is this more clearly seen than in his attitude to the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass: no real relationship in redemption means no Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. If we were not in a real relationship with God Almighty, then what need have we of His real presence amongst us? In Luther’s world, we are merely in a subjective relationship with our metal state of salvation. Lutheranism colonises the imaginary of the human soul with the poison of self-deception.

All of this has profound consequences for Catholic culture. For our tradition emerges as both doctrine and culture, but through the mediation of the person sanctified. And how we understand the sanctification of the person will have a profound effect on the culture, if any, that Catholicism creates. Whenever the sons of the Church begin to drift- neglect Her Tradition- either by compromising with the world or absorbing influences from pernicious doctrines- she loses her cultural imperative. Whenever Catholicism adopts a protestant mindset- either through how we pray (protestant praise and worship) or through doctrinal ambiguity (Alpha and Divine Renovation)- we abandon the very thing that makes us who we are. We may feel closer to our separated brethren, or even excited by the novelty of some “new idea”, but we are very far away from those who have brought us to where we are.

Conclusion

English-speaking Catholicism has always had to resist the decay of the Protestant influence. This we have done with greater and lesser success over the course of our history. Today we are doing a particularly bad job of it. So many different local Churches across the English-speaking world have adopted a kind of protestant praise and worship- either at Mass, as a way of organising their Eucharistic devotions or by arranging youth festivals in the spirit of evangelical revivals. Although this may be deeply unpopular in our age of never wanting to offend- but if we pray like them, we will begin to believe like them (lex orandi, lex credendi). This is a threat to Catholicism’s self-understanding and our identity. But even well before we organised “Catholic praise and worship” we had lost confidence in who we are. And we lose confidence in who we are when we lose touch with the countless generations who have come before us. We may be more “in tune” with those around us; but we are more divided from those who are actually a part of us. And while soever contemporary Catholicism looks elsewhere other than to the Tradition and the traditions- we will be forever bereft of Catholic culture, which is an integral part of the Church’s remedy for our sinful nature.

[1] Publius Cornelius Tacitus (c. AD 56 – c. 120), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars. Tacitus’ two major historical works, Annals (Latin: Annales) and the Histories (Latin: Historiae), originally formed a continuous narrative of the Roman Empire from the death of Augustus (14 AD) to the end of Domitian’s reign (96 AD). Tacitus’s Histories offers insights into Roman attitudes towards Jews. His Annals are of interest for providing an early account of the persecution of Christians and one of the earliest extra-Biblical references to the crucifixion of Jesus.

[2] Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (Latin: [c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire. His most important surviving work is De vita Caesarum, commonly known in English as The Twelve Caesars, a set of biographies of 12 successive Roman rulers from Julius Caesar to Domitian.

[3] Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (61 – c. 113), was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. Pliny the Younger wrote hundreds of letters, of which 247 survived, and which are of some historical value. These include 121 official memoranda addressed to Emperor Trajan (reigned 98-117). Some are addressed to reigning emperors or to notables such as the historian Tacitus. Pliny rose through a series of civil and military offices, the cursus honorum. He was a friend of the historian Tacitus and might have employed the biographer Suetonius on his staff.

[4] ST, IIIa q. 42, a. 4.

[5] The Great Famine of 1315–1317 (occasionally dated 1315–1322) was the first of a series of large-scale crises that struck parts of Europe early in the 14th century. Most of Europe (extending east to Poland and south to the Alps) was affected. The famine caused many deaths over an extended number of years and marked a clear end to the period of growth and prosperity from the 11th to the 13th centuries. The Great Famine started with bad weather in spring 1315. Crop failures lasted through 1316 until the summer harvest in 1317, and Europe did not fully recover until 1322. Crop failures were not the only problem; cattle disease caused sheep and cattle numbers to fall as much as 80 per cent. The period was marked by extreme levels of crime, disease, mass death, and even cannibalism and infanticide. The crisis had consequences for the Church, state, European society, and for future calamities to follow in the 14th century.

[6] The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as 50 million people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe’s 14th century population. The disease is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and spread by fleas and through the air. One of the most significant events in European history, the Black Death had far-reaching population, economic, and cultural impacts. It was the beginning of the second plague pandemic. The plague created religious, social and economic upheavals, with profound effects on the course of European history.

[7] The Western Schism was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 20 September 1378 to 11 November 1417, in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon simultaneously claimed to be the true pope, and were eventually joined by a line of Pisan claimants in 1409. The event was driven by international rivalries, personalities and political allegiances, with the Avignon Papacy in particular being closely tied to the French monarchy. The papacy had resided in Avignon since 1309, but Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome in 1377. The Catholic Church split in September 1378, when, following Gregory XI’s death and Urban VI’s subsequent election, a group of French cardinals declared his election invalid and elected Clement VII, who claimed to be the true pope. As Roman claimant, Urban VI was succeeded by Boniface IX, Innocent VII and Gregory XII. Clement VII was succeeded as Avignon claimant by Benedict XIII. Following several attempts at reconciliation, the Council of Pisa (1409) declared that both Gregory XII and Benedict XIII were illegitimate and elected a third purported pope, Alexander V. The schism was finally resolved when Alexander V’s successor as Pisan claimant, Antipope John XXIII, called the Council of Constance (1414–1418). The Council arranged for the renunciation of both Roman pope Gregory XII and Pisan antipope John XXIII. The Avignon antipope Benedict XIII was excommunicated, while Pope Martin V was elected and reigned from Rome.

[8] William of Ockham OFM (c. 1287 – 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the major intellectual and political controversies of the 14th century. He is widely known for Occam’s razor, the methodological principle that bears his name, and also produced significant works on logic, physics and theology.

[9] In philosophy, Occam’s razor is the problem-solving principle that recommends searching for explanations constructed with the smallest possible set of elements. It is also known as the principle of parsimony. It can be formulated as: Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem (Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity). It can be paraphrased as: of two competing theories, the simpler explanation of an entity is to be preferred.

[10] Thus, the effect of this declaration is that salvation becomes a ‘mental state’ as opposed to a real and renewed relationship with God that I receive. Much of the Protestant doctrine of justification is the application of nominalist categories to Christian theology.

[11] Although beyond the scope of this lesson, Luther’s own philosophical training was heavily influenced by nominalism as it came to be the dominant philosophical school of thought towards the end of the Middle Ages. In particular, Luther was attracted to nominalism’s assertion that God was completely free to do whatever He willed, even if the thing willed were a logical contradiction.

[12] Voluntarism- the primacy of the intellect over the will- is a necessary consequence of the hyper individualism of nominalism. In a nominalist world-view, knowledge of things is an act of the will: I ‘know’ when I use my will to name things, not when my intellect recognises the nature of things. It is thus also hyper subjective, because as there is no nature in things of the world, all my knowledge of them is derived from my subjective naming of them.