On Rome and Runnymede part II

There never has been a period of history,

in which the Common Law did not recognize Christianity

as lying at its foundation.

– Justice Joseph Story[1] –

Introduction

In last month’s lesson, we outlined some of the historical circumstances from which the Common Law of England emerged. We did not spend much time on the Common Law itself. In this month’s lesson, we want to show how Christianity came to be the foundation for a system of laws that would govern kingdoms and nation states. The Common Law, although profoundly Christian in its foundation, is not an explicit Christian project in its formulation. No one who examines the history of the Common Law could conclude that from the time of St Augustine of Canterbury, the Church set out to create a legal system that would enshrine Christianity as the law of England. That is not only undesirable, it is, I argue, also impossible. We must not imagine a monastery full of medieval monks, locked in their cells writing laws with the letters of St Paul in one hand and a quill in the other. And all this being done by candlelight as the cloister bells chime for compline. That may make for a wonderful opening scene in a play, it is not what the historical evidence shows.

The idea that everything begins as a project with a theory to guide it, is a very Modern kind of thing and something that can be antithetical to how Christianity itself shapes and moulds a Christian culture. Traditional Christianity, in order to Christianise the world around it, does not have to act through centralised plans and programmes. This sheds some light on why the Common Law, although a Christian institution, is not a Christian project. So, how does Christianity both render unto Caesar and at the same time conform all things to Christ? This is what our study of Tradition and our examination of the Common Law in this lesson must uncover.

A religion not of law is not a lawless religion

There is a superficial objection that states that Christianity should be incapable of forming a system of laws; either explicitly as a Christian project, or implicitly as an effect of Christian culture. As we have stated in earlier lessons, Christianity is not a religion of law, as taught by St Paul (cf Rom 10:4); and neither can it be captured by law (cf Gal 2:16). However, the idea that Christianity is not a religion of law seems to be manifestly false. Christianity is a religion full of laws: laws that govern Christian marriage, that regulate the sacraments; and laws regulating the moral life (contraception, adultery, IVF, etc.). It would seem that wherever you look in Christianity- you find a law. So, how can the principle that Christianity is not a religion of law be reconciled with the direct evidence that Christianity itself presents? And what has this got to do with the formation of the Common Law?

When we say that Christianity is not a religion of law, we are contrasting it with the Judaism from which it emerged. For the Jewish religion, to be right with God meant living according to the Mosaic law. The transformation from unrighteous to righteous was a function of whether I observed God’s laws- if you keep my commandments then you will be blessed (cf Deut. 18: 1-14). Christianity reverses this idea: if you love me, you will keep my commandments (cf John 14:15). The difference between these two principles is the difference between grace and law. Grace operates by transforming the man from the inside out- of writing the law on his heart (cf Jer 31:33; 2 Cor 3:3). In Christianity, one can only follow Christ (observe His commandments) because of grace (cf Philippians 4:13). We can only live a life according to the Beatitudes because the indwelling presence of Almighty God makes it possible.

Grace and law

This may seem like a tangential theological point that has little to do with the formation of the English Common Law. But the mindset it creates is fundamental to how Christianity forms Christian institutions. Just as the work of grace begins with the sinful man in order to transform him into another Christ; so too does Christian action begin with what is already present in the world in order to conform it to Christ. Christianity, when afforded the opportunity to shape the culture and its institutions, did not seek to overthrow what had come before it, rather it sought to sanctify it. This process of sanctification begins with resisting what is evil and then ordering the good to Christ. This is the first work of the Christian tradition: receive the good wherever it is to be found and order it to God Almighty.

When we think of how Christianity transforms the culture, we are naturally drawn to those things that changed in a very obvious way. One only need think of the influence that Christianity had on art and architecture. There is perhaps no more obvious and no more sublime example of how Christianity made a cultural impact than through the building of its monasteries and cathedrals. The ancient Roman basilicas that were scattered throughout the Empire, were slowly transformed from the columns and facades of Sempronia, Ulpia and Maxentius into the spires and arches of Notre Dame, Chartres and Westminster Abbey. But this aspect, although dramatic and incredibly effective, is but one aspect of how Christianity shapes the culture according to the nature of its own religious identity and self-understanding.

There are two aspects to Christian cultural transformation that reflect the two central doctrines of Christianity- the Incarnation and Redemption. The work of the Incarnation is where Christianity is revealed very much in a particular time and place. The Word became flesh at a particular moment in time. The Lord was born into a certain family, with a certain culture and a certain religion that all took place within a certain historical context. This is the temporal and physical manifestation of Christianity; and it is how Christianity captures the immanence of God- that He is close. Indeed, so close, that He became one like us in all ways except sin. This is the work of the cathedrals and why we can date and place them as belonging to a certain moment in history and to a place and its people[2]. That is an example of how Christianity continues the work of the Incarnation by making the glory of the unseen God tangible in the history of the people He chose to redeem.

However, Christianity must also continue the work of Redemption. And that is a work intimate to the inner reality of the thing that must be sanctified. It is a work from within because it is a work of transformation according to the order of grace, particular to the nature of the thing to be transformed. Which is also a mystery to us. It is a work that universalises the coming of Christ by informing all reality throughout time with a similarity to Christ. The Lord came in a particular historical moment, but His work must also transcend that history. The incarnation of Christ is configured by the conditions into which he was born, but it must not be confined to them. There would be no point to the coming of Christ if it were limited to one people, one language or one set of historical circumstances. Christ did not come to redeem a generation; He came to redeem all mankind. And so, a second way that Christianity transforms, is by universalising the good that has been handed to it- and this it did when it transformed Anglo Saxon custom into English precedent and Common Law. This is what we will examine in this lesson. These two manifestations of the Christian genius capture the two ideas most central to our understanding of the divine: God is close to you (immanence); but He is also infinitely beyond you (transcendence). The wisdom of the Church’s tradition teaches that cultural influence does not require everything that is essentially Christian to ‘look Christian’ in order to ‘be Christian’. Everything Christian is informed by the Cross; it does not have to be in the form of a cross.

Reform your life. Reform the law

The English Common Law was born in the immediate context of two great moments in European history. The first was the ambitious reform movements of the early Middle Ages; and the second, was the Norman conquest of Britain. By the 10th century, the Carolingian Dynasty[3] that had governed much of church life in western and central Europe was in severe decline, which brought with it moral and social decay. In particular, the moral life of the clergy and the Investiture Controversy[4]. The two major developments that dealt with these issues were first, the Cluniac Reform[5], where monasteries and monastic life were transformed; and second, were the Gregorian Reforms[6] of Pope Gregory VII[7], which dealt specifically with the moral life of the clergy and the independent functioning of the Church from the state. This period, like so many others, is a fascinating period of history and is worthy of your attention, but beyond the scope of this lesson.[8]

At the heart of the Investiture Controversy was a theological, spiritual and practical question with which the Church must contend: does Christianity scale from the personal into the political? Christianity is a particular relationship between the baptised person and God Almighty. Through redemption not only are we forgiven; we are elevated into the inner life of God through our conformation to Christ through grace- we are made children of God. That is an intensely personal reality. How then does a religion of personal redemption and sanctification relate to civil and secular society, if at all? These are questions that each generation needs to answer. But it must do so according to the received wisdom of the Church, and not the latest trend or fad that may pass itself off as being wise.

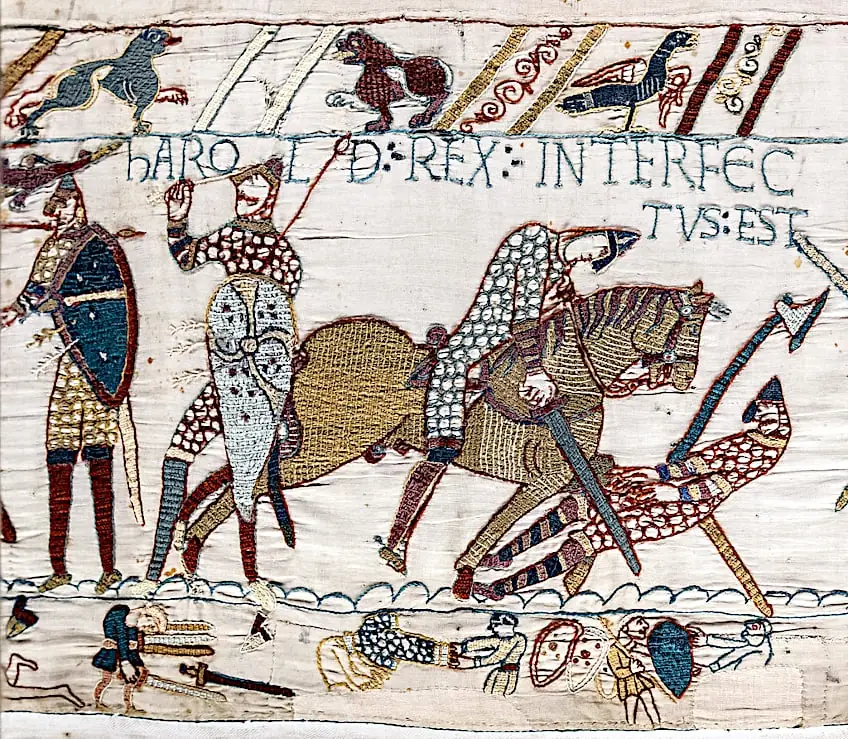

Hastings and the feudal system

The Battle of Hastings was fought on October 14 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, Duke of Normandy, and the English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conquest of England. It was a decisive Norman victory. William was crowned King of England on Christmas day in 1066. The legal landscape that William inherited after Harold’s defeat was far from un-sophisticated. Prior to 1066, much of England’s legal business took place in the local folk courts of its various shires and hundreds[9]. A number of other individual courts also existed: urban boroughs and merchant fairs held their own courts, and large landholders also held their own manorial and seigniorial courts as required. The problem with the pre-Conquest legal system was not its lack of sophistication, but rather its lack of commonality. It was based more upon local customs as they had developed after the Roman exodus than it did on universal norms and rules; even though a politically unified England had existed since the 9th century.

The genius of the Norman conquerors was their willingness to preserve the good where they found it and their ability to build upon it. A profoundly Christian principle. They did not impose a new body of substantive law in England, but rather they preserved and developed the pre-existing social and legal structure in order to allow a common legal framework to flourish. The newness that the Normans introduced into England was the feudal system. The feudal system, although materially very similar to the Church’s own system of government, was not Christian because the ecclesial structure of pope-bishops-clergy-faithful was repeated in the feudal structure of king-nobles-knights-people. The material correspondence between them is undeniable, but inconclusive in so far as the Christian foundations of the Common Law are concerned. Rather, at the heart of the feudal system was the mutual promise. In addition to the loyalty that subjects owed to the king, each landowner would swear an oath of fidelity to the immediate superior in the chain, agree to pay a percentage of revenue as ‘rent’ or ‘tax’; and if necessary, in times of military conflict, he would provide military resources for combat. In return, the king (and the next superior in the hierarchy) promised assistance to their tenants in times of need. On the surface, this sounded like an effective way of administering civil society. But like all systems, they are subject to the corruption and decay of sin.

Mutual promise – mutual service

Although they varied considerably in ability and willingness, the idea that governed the feudal system was that the more noble the office, the greater the burden of responsibility and thus the heavier the obligation of service. This is another profoundly Christian idea (cf Matt 23:11). Thus, there is no greater duty of service owed in the feudal chain than that of the king, who stood at the top of the hierarchy. And one of the prime responsibilities of the monarch was to address complaints from his subjects. Accordingly, as the king travelled his kingdom, he ‘held court’ and received petitions from his people who had complaints about the local administration of justice. The Norman system of government relied heavily on the idea of the Curia Regis (king’s court) that would travel throughout the realm and hear the petitions of suitors in person.[10] The fact that the king’s court travelled throughout the realm was a practical condition for the establishment of a law common throughout the land. The practice of the curia regis however, relied heavily on the Christian idea of service as it was embodied in the feudal system and its custom of mutual promise.

The historical context outlined above, although very brief, gives the reader an insight into the background for the creation of the Common Law. However, it is not direct evidence that the Common Law is a Christian institution. The fact that Christians were involved at a time of Christian activity when the Common Law was being formed does not prove the Christian foundation of the Common Law. We have established the Christian context for the development of the Common Law; not that Christianity is a causal factor in the Common Law. And this is why it becomes very important to understand just how Christianity forms and builds a Christian culture. For the Christian foundations of the Common Law are not found in the fact that the Church’s Canon Law became its backbone, or that the Christian Gospel was transcribed into legal procedure. The most effective way that Christianity forms a culture is from within- by shaping the central ideas of that culture and then forming the habits of the people within that culture. Christianity although always effective, is not always obvious (Mark 4:26-28). That is why so many today when they talk about a post-Christian West, do not understand just how profoundly Christian the West actually is. Not everything Christian has to be obviously Christian. The genius of the Christian foundation of English Common Law emerges from within.

However, even though this transformation is internal to the workings of the culture; because it first shapes ideas that then form habits, the institutions that result from these habits must function externally in the world according to the Christian principles that created them. Even though their transformation takes place from within, they visibly function in the world according to the proper powers with which they have been created. How Christianity transforms reality may be something hidden from view, how that reality once transformed must function, does not (cf Matt 5:15-16). Thus, there is more evidence for the Christian foundations of the Common Law in the proper functioning of its institutions than in the formulation of its laws: from the effects of Christianity can we best determine its causal power (cf Jn 13:35). And there are three main institutions of the Common Law which reveal its Christian foundation.

Precedent

One of the reasons why the Curia Regis proved to be so popular was its perceived impartiality. As there were several degrees of separation between the king and the local administration, petitioners believed that the king or his delegate were less likely to be parochial and affected by local prejudice. Thus, the king’s justice was preferred to that of the local (pre-Conquest) courts; even though those courts were left largely untouched by the Norman conquerors. However, this separation brought with it several problems to solve. And it was how the English Common Law solved them that furnishes the best account for why its foundations are Christian.

The first problem was how to administer justice throughout the land that would be both consistent and uniform. The idea that like cases should be treated alike required some principle or practice that would guarantee it. Every first-year law student in a Common law jurisdiction learns the phrase stare decisis (to stand by one’s decisions), which is an abbreviation of the Latin maxim: stare decisis et non quieta movere (to stand by one’s decisions and not disturb the undisturbed). This is what we refer to as precedent. Without delving into its legal history, there is no treatise or tome that explains exactly its ancient origins or why the idea of precedent was so persuasive. What is important for our discussion is to note that the idea of precedent emerged from within the practice of seeking justice. It was a habit before it was a doctrine (institution)[11].

The origins of the idea that those who administered justice (judges) should treat as law the decisions that were handed to them is really found in the Christian habit of tradition- that the good once discovered must be handed on; even if each generation is called to build upon it. Such is the profound effect of Christianity in shaping Christian culture, that so many of our cultural practices appear to us as second nature. But this is how grace itself elevates- from within according to the order of grace but in complete conformity to the nature of thing to be elevated. Precedent emerges not as some Christian project, but rather as a practice that derived from Christin tradition- received wisdom- and the culture it created.

The Jury System

A second challenge that the Curia Regis and this emerging system of common law posed, was that the kind of impartiality that was so key to its popularity, also meant that the king and his deputies actually lacked necessary knowledge in order to decide just outcome in these disputes. Thus, the king’s court attempted to circumvent this problem by an appeal to divine intervention, or what came to be known as trial by ordeal: that the ordeal would identify the guilty party or the wrong doer.[12] The ordeal was commonly used in criminal cases. Two common forms were the scolding of the hand with boiling water; or the casting of the accused into water to see if they would float. Trial by battle was an innovation introduced by the Normans that was largely used in civil cases[13]. The idea in both cases was that God would not let the innocent party be the injured party.[14]

Leaving aside any questionable theological interpretation (cf Matt 16:4), it is easy to imagine that it might prove effective as it would ensure someone who was fabricating his story might think twice before bringing that story to the court and risking the ordeal. The Church banned participation of clergy in trial by ordeal in 1215. Without the legitimacy of religion, trial by ordeal collapsed. In its place emerged a practice that was completely new and novel. It is often referred to as trial by compurgation or the ‘wager of law’. This was a process where the travelling justice would require sworn statements of those amongst the local townsmen who, knowing the details of the situation, would swear an oath as to the truthfulness of the testimony given. As this system proved to be somewhat of a return to the problems of the parochial pre-Conquest local courts, Henry II in the 12th century adopted a system known as the Grand Assize.[15] This system eventually evolved into the election of twelve local men to first swear by the truth of the statements made; which then later transformed into a group of impartial men who would hear the evidence and then decide on the guilt or innocence of the parties. This was the basis of the jury system.

The Christian underpinnings of the jury system are not found in the Church’s banning of trials by ordeal or the selection of ‘twelve men’. Although these do speak to the importance of the Church and Christianity. Rather, the uniqueness of the jury system was the importance given to the ordinary man and his interior life. That each man was afforded the same dignity to the point that the guilt or innocence of any man could be judged by a group of his peers. This idea was formalised at Runnymede and the signing of Magna Carta, where it was declared that even the king was not to be above or beyond the law. This is an idea that can only emerge from within the teachings of Christianity: that each man was not only made in the image of God, He was redeemed by the blood of that same God; and because of this, the commoner mattered as much as the king. At least in so far as justice throughout the land was concerned. Thus, the universality of the dignity of the person was something that God willed and that the Church placed at the very centre of Christian culture.

Chancery and Equity

As the common law become more popular, it solidified into a system of law based on the virtue of justice: the constant and perpetual will to give each his due. This meant that the wrongs suffered must be remedied by an equal and commensurable compensation. However, this inevitably led to the legal system being weighed down by the sheer volume of cases, given its mass appeal; but it also meant that certain wrongs could not be addressed. As the king’s bench became more popular, complainants brought before the court cases of injustices faced in the common law courts. At first, the king responded in person or through his officers to these injustices. After a while, as this grew in popularity, this office was delegated to the king’s chancellor.

The Lord chancellors were oftentimes trained as priests and thus took a different approach to the common law. The chancellor did not limit himself to precedent, but rather relied upon Christian precepts. The lord chancellor possessed as one of his titles that of Keeper of the King’s Conscience; and, hence, the Court of Chancery was often called a Court of Conscience. Its procedure did not involve the presence of a jury and it differed from the courts of common law in its mode of proof, mode of trial, and mode of relief. The relief administered was so ample in scope as to be conformable in all cases with the absolute requirements of a conscientious regard for justice. Among the most eminent of the Chancellors of England was Sir Thomas More who laid down his life rather than surrender the Catholic Faith. It is today referred to as the (court of) Equity. Equity provides discretionary relief based not only on the injustice faced but also on the moral character of the person seeking redress. One of the first maxims of equity[16] is that he who seeks equity must approach with clean hands. The maxims of equity are a fascinating rendering of Christian principles and virtue.

Again, as evidence for the Christian foundations of the Common Law, Equity represents both a recognition and an elevation of the sanctity of the human person. That the interiority of each human person- his intellect, will and memory- matter a great deal. To the point, that it became the basis for a legal system. Equity is such a shining example of how the principles of Christian redemption scale from the personal into the political via the culture that Christianity itself creates.

Conclusion

The jurist John Wu remarked: while Roman Law was a deathbed convert to Christianity; the Common Law was a cradle Christian. This is perhaps why a ‘new law’ was so effective in establishing the New World. In arguing for the inner formation of the Common Law according to Christian principles, I do not want to give you, the reader, the impression that early English jurists were unaware of their Christian faith and its importance to the emerging legal framework. I am not advocating for the ‘anonymous Christian’ or the surreptitious Christianisation of the Common Law. There is more than enough evidence to suggest that they were not only aware of the importance of Christianity, but made conscientious and determined efforts to ensure that Christianity was their guiding light. Rather, I am arguing for the idea that the transformative power of Christian redemption is worked throughout the history of Western Civilisation as an inner dynamism according to the order of grace, and in complete conformity with the nature of the thing to be transformed. Christian cathedrals are a timeless rendering of the Incarnation; the Common Law is a dynamic rendering of Christian Redemption.

Increasingly, modern Catholicism is looking for someone to fix what is broken in the church and in the world. We want someone to fix the internet, to fix our politicians or to fix the broken relationship between men and women. We are looking for someone to right the wrongs as we perceive them. This is a complete break from the ancient and immemorial Christian tradition of living into revealed truths by actually living them out. Tradition teaches that we act out the truths- the received wisdom- that has been handed to us. Christian Tradition is a moral response to revealed truth. The modern mentality of looking externally for a solution that instead requires an inner transformation is a kind of mental condition. It is also a spiritual problem. We do not need someone or some programme (local synod) to ‘fix’ what is broken. Rather we need to practice Christian habits in order to build a Christian culture. Which is the way of Tradition. And the unbroken Tradition of Christianity is that you cannot fix the world until you first fix the man. This is not just a practical consideration; it is a testimony to the very principle of Christianity holds so dear: that each person is worth all the blood of Christ.

[1] Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee and United States v. The Amistad, and especially for his Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, first published in 1833

[2] Although somewhat outside our topic, this work of incarnation is not limited to time and place. No one who thinks with the mind of Christ- the heart of the Tradition- believes that Chartres is locked in the past. There is a universality to the splendour of the Gothic, for example, that transcends both time and place. However, even though it transcends time and place, it does not exist without that time and that place.

[3] The Carolingian dynasty was a Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The dynasty consolidated its power in the 8th century, eventually becoming the de facto rulers of the Franks as the power behind the Merovingian throne. In 751 the Merovingian dynasty which had ruled the Franks was overthrown with the consent of the Papacy and the aristocracy, and Pepin the Short, son of Martel, was crowned king of the Franks. The Carolingian dynasty reached its peak in 800 with the crowning of Charlemagne as the first emperor of the Romans in the West in over three centuries. Charlemagne’s death in 814 began an extended period of fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and decline that would eventually lead to the evolution of the Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire.

[4] The Investiture Controversy was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture), abbots of monasteries, and the Pope himself. It began as a power struggle between Pope Gregory VII and Henry IV (then King, later Holy Roman Emperor) in 1076. The conflict ended in 1122, when Pope Callixtus II and Emperor Henry V agreed on the Concordat of Worms. The agreement required bishops to swear an oath of fealty to the secular monarch, who held authority “by the lance” but left selection to the church. It affirmed the right of the church to invest bishops with sacred authority.

[5] The Cluniac Reforms were a series of changes within medieval monasticism in the Western Church focused on restoring the traditional monastic life, based on the rule of St Benedict. The movement began within the Benedictine order at Cluny Abbey, founded in 910 by William I, Duke of Aquitaine (875–918). The reforms were largely carried out by Saint Odo (c. 878 – 942) and spread throughout France and into England (the English Benedictine Reform).

[6] The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the papal curia, c. 1050–1080, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be named after Pope Gregory VII (1073–1085), though he personally claimed his reforms, like his regnal name, honoured Pope Gregory I.

[7] Pope Gregory VII (c. 1015 – 25 May 1085), born Hildebrand of Sovana, was Pope and ruler of the Papal States from 22 April 1073 to his death in 1085. He is venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church.

[8] The effect these two reforms had on the Christian mind again, cannot be underestimated. They were truly a high point of the Middle Ages. For the first time since perhaps the early Church, Christianity in a very self-conscious manner asserted both its independence from the state and its superiority to the state. If the reader is interested specifically in the topic of the relationship between the spiritual and temporal orders (Church and State), then I recommend that he read Gregory VII’s Dictatus Papae, Boniface VIII’s bull Unam Sanctam and Pius IX’s Syllabus. This topic, although essential, is not treated specifically in this lesson.

[9] A hundred is an administrative division that is geographically part of a larger region.

[10] During the 13th century, the great council and the small curia separated into two distinct bodies. The great council evolved into Parliament and the small curia evolved into the Privy Council. The small curia regis then is “the very distant ancestor of the modern executive, the Cabinet acting for the authority of the crown.” Early government departments also developed out of the small curia regis, such as the chancery, the treasury, and the exchequer.

[11] The eminent legal scholar and jurist Sir Edward Coke, is often considered the father of the modern idea of precedent. Somewhat thanks to the wirings of Bacon.

[12] This is not the proof of Christian influence for which I will be arguing.

[13] Paul Hyams (1981). Arnold, Morris S. (ed.). On the Laws and Customs of England. Essays in Honor of Samuel E. Thorne. University of North Carolina Press. p. 111

[14] An interesting little story. Trial by battle was never officially abolished in England, even though the practice had long since been abandoned. In Ashford v Thomas in 1819, one of the parties sought to claim the right to engage in trial by battle in lieu of the ordinary court process. It was only then that parliament rushed to pass a bill outlawing the practice.

[15] The Grand Assize (or Assize of Windsor) was a legal instrument set up in 1179 by King Henry II of England, originally to allow tenants to transfer disputes over land from feudal courts to the royal court.

[16] Maxims of equity are legal maxims that serve as a set of general principles or rules which are said to govern the way in which equity operates. They tend to illustrate the qualities of equity, in contrast to the common law, as a more flexible, responsive approach to the needs of the individual, inclined to take into account the parties’ conduct and worthiness.