“Jesus said to them, ‘Therefore every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old’”

(Matthew 13:52)

Introduction

Last month, I left you on a cliffhanger: how can we have a fully formed Church at Pentecost, if one of the sources of the Deposit of Faith- Sacred Scripture- had not even been written? If the Church at Pentecost were somehow incomplete, then we would have to question how the truth could be preached and souls guided to heaven. It would seem that being one of the first disciples was quite a disadvantage. It would also cast some doubt on whether being a Christian at any time, was worth it at all. The purpose of this article is twofold. The first, we want to work out not only how the Church came to write the New Testament (NT), but how She knew to recognise it as Sacred Scripture once it had been written. After all, the Church did not have the advantage of being able to refer to the NT in order to decide what was Scripture. The second, we want to see whether the Church’s approach and eventual resolution of this problem can shed any light on our present malaise.

Most Catholics have probably wondered at some time- where is the original copy of the Bible? Is there, deep within the Vatican Library, a room where they keep the Original Bible under lock and key? I have been to the Vatican Library and I can tell you that there is no copy of the original there. Or at least, none that anyone showed to me. However, there are some very ancient Bibles- fragments and codices- kept there[1]. One of the most enjoyable subjects I did for post-graduate studies in Rome, was a course called Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the Old and New Testament. It was taught by a Jesuit biblical scholar called Fr Stephen Pisano S.J. who has since gone to his eternal reward. He will be sorely missed by many a student who passed through his classes at Piazza della Pilotta, 35.

Now, a course on biblical textual criticism might not sound like the most thrilling thing to do in Rome. In fact, it possibly sounds like about as much fun as burnt toast. Nothing could be further from the truth. The history of the biblical text is quite literally a cross between an Agatha Christie Whodunnit and an Indiana Jones movie. To properly study the history of the biblical text is to be immersed in a world of esoteric clues deriving from Mesopotamian legend and Egyptian hieroglyphs. It means to climb through the Bedouin caves of the Judean desert in search of lost treasure.[2] It requires that you, by sheer chance, tear down the wall of a long since abandoned Jewish synagogue in order to reveal a Genizah that had been lost to both time and memory.[3] The history of the text of the bible is the world’s oldest and greatest mystery story that you can actually follow, because it is so incredibly well documented for something that is absolutely so ancient. It is so extraordinary, that even crusty old academics have to admit- it does taste of the miraculous. But what is at the heart of the history of the biblical text? And what has it got to do with anything we have to say about the Tradition of the Catholic Church? We will dedicate this month’s essay to trying to resolve some of these questions for you.

Which books in what Bible?

Most Catholics, at least those in the English-speaking world, are introduced to the problem of the text of Sacred Scripture thanks to a Protestant acquaintance. Catholics have 72 books- 73 if Lamentations is considered a separate book from Jeremiah- while Protestants, generally, have 66. In case you’re wondering, this what they are missing[4]:

- Tobit

- Judith

- Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon)

- Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus)

- Baruch

- 1 Maccabees

- 2 Maccabees

Although this is where most Catholics are first introduced to the question of the origins of the Bible, this is not the question I will be answering here. At least not directly. Its history is definitely worth your time and attention, and there are many places that you can find excellent summaries. Our question, the one I will be looking at today, regards a very specific topic: how do we know what books should be in the Bible in the first place? This is the problem of the biblical canon.[5]

Over the centuries Christians have disagreed about which texts constitute Scripture, and about what the contents of the Bible should be. The Jews too, have had their own debates about the books of the Old Testament. The question of the biblical canon did not arise with Luther, although he reintroduced a problem that had been resolved long before he emerged on the scene. However, for Catholics, the origins of the Bible raise some very important questions about the origins of the Church and what we believe.[6] The problem of the biblical canon is often reduced to a debate about which books should be included in the Bible. The question, however, goes beyond books and also looks at questions about which versions of books- Septuagint[7] vs. Masoretic text[8]; and about which passages within those books should be included- Deuterocanonical passages[9] and “non-original” passages.

If we are to give a robust account of how Scripture came to be, there are three questions we must answer:

- Why did Christians think it necessary to write down the words and deeds of Jesus?

- Did they consider what they were writing to be adding in any way to the Jewish Scriptures?

- How did the Church recognise the canonical books as distinct from other Christian literature?

Question 1: What evidence do we have that explains why Christians wrote the New Testament?

At the end of Matthew’s Gospel, we have the Great Commission: Go you therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them… Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you… (Matt 28: 29-30). There is no evidence to suggest that the Lord ever instructed His followers to write anything down. It may even be argued, that to stop and write things down would impede the mission He expressly gave them. However, most of the first followers of Jesus were Jewish and had a particular understanding about the religious and cultural significance of the written word. The Christian religion was not founded in a vacuum, but rather sprang from a rich tradition that shaped the ideas and actions of those first century followers. Some of the answers we need are rooted in the religion and culture of second-temple Judaism.[10]

OT origins of the NT

It is clear in the NT, that the concept of Scripture was relevant at the time of Jesus; and Scripture represented the Word of God. We find significant evidence in the Gospels (cf. Matt 23:35; Luke 11:51) and throughout the writings of Paul (cf. Rom 9: 15, 17, 25-26). It seems clear that both Jesus and His disciples accepted the Scriptures as divine revelation (2 Tim 3:16; 2 Pet 1:20-21). However, this evidence alone does not explain why early Christians wrote a NT. It only explains why they would reverence the OT.

The first instruction to write down the words of the Lord is given to Moses: Then the LORD said to Moses, “Write down these words, for in accordance with these words I have made a covenant with you and with Israel.” (Ex 34:27). There are two important considerations to note here. The first, is that writing down God’s spoken word is a foundational idea for the Jewish religion and the culture it created. One could reasonably argue that because of this instruction, literacy and religious formation are synonymous in the Jewish mindset. If God Himself has commanded us to write, then the people must learn how to read, for God wills to instruct us through the written word. This is part of the reason why the Jewish religion and Jewish culture are so intricately interwoven. The second, is that the written word of God forms a covenant between God and His people. This means that the concepts of covenant and canon are intimately related.[11] To the Jewish mind, and the Christian mind that emerged from it, the written word of God is no dead letter; rather it is a relationship. The next question to ask is- what kind of relationship?

Covenant: a written agreement

In the Jewish religion, a covenant, of which there are several in the OT (Adam, Moses, Abraham, Isaac, Daivid etc) possessed many elements of Near Eastern suzerainty.[12] In Middle Eastern culture, suzerainty emphasised the importance of the written word, public proclamation in the assembly of the people, conditions for securing the terms of the law, the requirement of a loyal assent from the people and curses and anathemas preventing deviations and violations from the normative texts (Cf. Ex. 24; Dt. 31).[13] Suzerainty required that the terms (laws) of the relationship (treaty) must be made public in a very prescribed manner. (We will return to this idea, when we look at the ritualistic and liturgical influence on the formation of the canon.) What bound the parties was a certain and defined external conformity of the tributary to the suzerain under the law of the treaty, whilst allowing a certain internal freedom for the operations and workings of the polity. Internal freedom was permitted, while external conformity was expected. We must now explain how this Jewish understanding of OT covenant influenced the Christian writing of the NT canon.

In the Exodus account of the Decalogue, we have Moses recording for the reader that the Law of God (Decalogue) was written with the Finger of God:

It is a sign between me and the children of Israel forever… And he gave unto Moses, when he had made an end of speaking with him upon mount Sinai, two tables of testimony, tables of stone, written with the finger of God. (Ex 31: 17-18).

Now, the connection between God’s law and God’s finger is not immediately clear in the text. Although used several times in Torah, the imagery of the Digitus Dei (Finger of God) is also picked up a number of times in the NT (Cf. Lk 11:20; Mt 11:28); and most memorably in the case of the woman caught in adultery (Jn 8: 1-11). Without giving a detailed account of each example, the spiritual truth that this connection (imagery) conveys, is that God’s law must not just instruct the listener externally, it must touch him internally. In John’s Gospel account (Jn 8: 1-11), the scribes and Pharisees question Jesus directly on the consequences of the law. Jesus, hearing their question but ignoring it, then stoops down to write on the ground with his finger (Jn 8:6), after which he then gives the woman’s accusers a law: whoever is without sin, let him cast the first stone (Jn 8:7). The Gospel then instructs us, after having given the command, again he (Jesus) stooped down, and wrote on the ground (Jn 8:8). The repetition of the Lord’s action- stooping down to write- is on purpose. It reveals that what has been said, must now be written a second time- not just in the dirt, but on the heart. It is in that moment, the Gospel tells us, that the accusers being convicted by their own conscience, went away one by one (Jn 8:9). The hearts of the scribes and Pharisees have been touched (changed) by a law, as they drop their rocks and abandon their intentions of stoning the woman. This particular Gospel story, given its parallels with the Exodus account of the Decalogue, is the revelation of not just a new law, but of new Law-Giver. However, what is memorialised in the Christian scriptures, is not simply a new set of instructions, but rather a new presence of God. A presence of God that now changes the heart, not simply instructs it. But this presence of God still reverences the same old law: why?

To the Modern mind, largely due to the influence of legal positivism, the law is merely a tool for regulating human behaviour and not the inner world of the person. We do not expect that once a law is proclaimed that it will necessarily affect a person’s internal dispositions. He may change what he does, so as to avoid punishment, but the law does not affect his internal conscience. To the emerging Christian mind in the first century AD, this was not the case. The Jewish tradition from which this mind emerged, cherished the law as God’s presence amongst his people- it was a reminder that God’s favour had been visited upon them. To the Christian mind that followed, the New Law stood for something far greater than God’s presence amongst us- it represented God’s presence as one of us. The Jewish tradition of the law shaped the Christian Tradition of how it would reverence the Law-Giver. So, how does the OT concept of law and covenant influence the Christian understanding of the law-giver in any religiously meaningful way? And what use was this ‘idea’ in the context of Christian redemption and the writing of the NT?

Redemption’s work

After the Fall of our first parents, in order to redeem us, not only did our sin need to be overcome so that original justice could be restored, rather the human heart had to be remade so that the intimacy and immediacy of our relationship with God could be re-established. For our redemption to be complete, God did not want mere external obedience to His law from us, what he desired was conformity of our heart to His. We did not have to become just more compliant to Him, rather he wanted us to become more like Him. From the moment of our creation, we were made in the image and likeness of God. However, after the fall, even though the image remained, although tarnished, we lost our likeness unto God. Once sin had robbed us of that likeness, redemption had to ensure that it was restored. However, without God’s grace, this is not possible. The question that looms across the OT is what purpose does its covenant serve, if what it means to achieve is not actually possible according to the terms of that covenant- the old law could not make new hearts. This is not just something that Christians need to ask, the Jews themselves needed to come to terms with this very question. In the book of Jeremiah, the issue is raised and a prophecy is delivered:

Not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers… in the land of Egypt… which they broke… But this shall be the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel; After those days, says the LORD, I will put my law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts; and will be their God, and they shall be my people. (Jer 31: 32-33).

And so, we are left wondering what actual purpose does the OT covenant serve if it cannot achieve the thing that is most required.

St. Paul, in his letter to the Galatians, answers this objection when he instructs us that the law is a pedagogue, and that it brings us to Christ so that we might be justified by faith[14]. What St Paul is referencing, is that the OT covenant is propaedeutic to a real relationship with God- a relationship that is constructed by Grace as opposed to one that is instructed by law. But the human heart, before it could be remade, had to relearn certain truths and to remake certain habits. That before the law of God could be written on the human heart by grace, both the human intellect and will first had to be prepared by the law so that they could be re-ordered. That preparation was the work of the Old Covenant, and it had to be done before there could be a New.

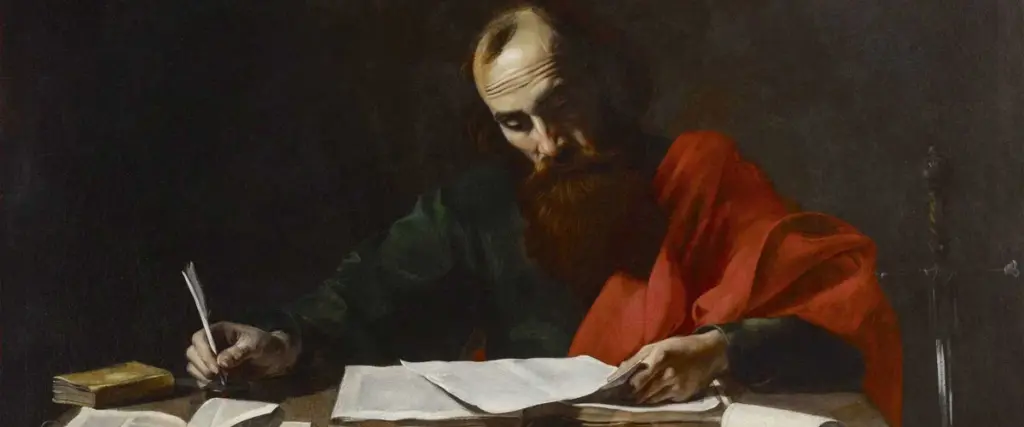

Painting: Saint Paul Writing His Epistles, attributed to Valentin de Boulogne.

The law that could not remake the heart, had to touch the heart by re-creating certain habits of the people destined to be redeemed. And the principal habit that had to be restored first, was the very first habit we lost in the fall- that we no longer walked with God. When Adam fell into sin, he ceased walking with God in the Garden, rather he hid himself in the bushes. Thus, the principal habit that the law restores, was that the people of Israel had to learn once more to walk not just in the ways of God (externally in the law), but rather to walk with God (in intimate relationship). The balance between external conformity and internal freedom is the model for the OT covenant under the form of Near Eastern suzerainty. A life of righteousness according to the law was never destined to be external correspondence alone, but rather to shape the internal freedom of the person. And this freedom was to be shaped by the habits that the law created. Hence the imagery of God’s law and God’s finger teaches that the law would touch the heart of the hearer by producing certain habits in his life; which in turn produced a certain, albeit external, likeness to God and His righteousness. Accordingly, the law of God once external to the human heart at its hearing, must be written on the heart through the habits it engendered. But the law, because it was just a law and not Grace itself, could only take us so far. But where it did lead us, was essential in forming the Jewish mind in seeking the likeness of God by imitating the actions of God through observing the law of God. This is the religious culture of second temple Judaism, which in turn, shaped the Christian intellect that emerged from within its context to seek, to recognise and to think with the mind of Christ. The idea of a new canon emerged from within the context of the promises fulfilled in the New Covenant.

The Christians begin to write

In the Jewish mind, the Tanakh (canon) was a manifestation of the relationship (covenant) between God and His people. Thus, what was experienced in reading the word of God was not just an account of events and norms that must be applied, rather what was being experienced was the presence of God himself. What the Jews recognised in the word of God was not something external to themselves or to God, rather what they were recognising was the very presence of God himself. Hence the extreme reverence with which the Jews treated the scrolls, the genizah, which is part of the reason we have such historical evidence for scripture itself. As we mentioned earlier.

Now, to the mind of the first Christians, this was entirely familiar to them and so a new presence of God required a new written memorialisation. Although Jesus did not issue a direct command to write down His words, as in Exodus, His command to do this in memory of me at the last supper (cf. Mk 12:25; Lk 22:20; 1 Cor 11:25), takes place in the context of the revelation of a new law- a new commandment I give unto you (Jn 13:34)- and a new covenant- for this is my blood of the new covenant, which is shed for many (Mt 26:28). The revelation of a New Covenant required that the it be written down: a New Covenant required a New Canon[15]. However, in the Christian experience, they were not merely recording the words God spoke, but rather they were memorialising the Word of God itself- they were not capturing the prescriptions of God’s presence in the law, rather they were capturing God’s presence as one of us. Thus, the Christians began to write their own scriptures, not as the result of a command, but rather of a tradition. A tradition that shaped a religious culture of the written word which Christians received. But also transformed.

Conclusion

The Christian scriptures were not written because of an express instruction. It was not necessary. Jesus did not expressly command his disciples to write down what he said or what he did. The Church herself did not commission authors to chronicle what happened. And despite the arguments of some biblical scholars, the Christian scriptures were not written by committee. Rather, there pre-existed a religious tradition that prised the memorialising of God’s presence in the written word- that understood the immediate connection between covenant and canon. The idea for writing the NT is the fruit of a religious tradition that is grounded in a particular culture.

Next month, I will answer the last two questions: did the Christians know what they were doing would add to the Scriptures, and how did the Church come to recognise some of these writings as Sacred Scripture.

[1] Although there is no “Original Bible”, the oldest known copy of the Bible is kept in the Vatican Library. The Codex Vaticanus (B or 03 in the Gregory-Aland numbering of New Testament manuscripts), contains the majority of the Greek Old Testament and the majority of the Greek New Testament. It is one of the four great uncial codices: Codex Sinaiticus (א), Codex Alexandrinus (A), and Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (C). Using the study of comparative writing styles (palaeography), it has been dated to the 4th century. I have seen a complete copy of this Bible!

[2] The story of the discovery of earlier Hebrew Manuscripts, some dating from the pre-Christian era in the Judean desert is an incredible story. These manuscripts were hidden in the first and second centuries AD in various caves near the Essene settlement of Khirbet Qumran and remained hidden there for two thousand years until their discovery in 1947. They were quite literally discovered by a Bedouin shepherd who had lost a sheep in one of the caves. The manuscripts were sold at a local market where they eventually came to the attention, by chance, of prominent scholars who were in the area doing other research. This is the story that you know as the Dead Sea Scrolls.

[3] During the second half of the nineteenth century many fragments of the Old Testament were in an Old Cairo synagogue which until AD 882 had been the church of St. Michael. They were discovered in an abandoned Genizah (גניזה: Hebrew/ Aramaic root to hide) as it had at some point been walled over and its existence forgotten. A Genizah was a kind of storage room for worn or faulty manuscripts where they were be kept until they could be properly disposed of by ceremonial burial. It was by a sheer accident that these precious manuscripts were both forgotten and then later discovered.

[4] These are known as the deuterocanonical books of the Bible- literally, a “secondary canon.” We will have more to say about them a little later on.

[5] The biblical canon is the set of texts (also called “books”) which a particular Jewish or Christian religious tradition regards as part of the Bible. The English word canon comes from the Greek κανών, meaning “rule” or “measuring stick”. We will be concentrating on the canon of Catholic Scripture.

[6] If we do not give a clear account about the origins of the Bible, we can easily end up with a very self-contradictory and ultimately illogical understanding of the issues. And there is a complicating factor: nowhere in the Bible is there contained a list of books that should be in the Bible. Even if there were, say in the Book of Acts, a list of the “canonical books,” that list would be self-referential and thus non-demonstrative. Its argument would be circular- it would be pointing to itself because it points to itself. It may be true- but it would not prove itself to be true. It would also seem that the Apostles left no written list of what books should be in the canon.

[7] The Septuagint, known as the LXX, is a set of ancient Greek translations of the Old Testament. It was made about 300 to 100 BC. Today the LXX is synonymous with the Codex Vaticanus, which we mentioned previously. It was quoted as Scripture by Jews such as Philo (d. 50 AD) and Josephus (d. 100 AD). More than half of the Old Testament quotes in the New Testament come from the Septuagint. It also appears likely that Jesus quotes the LXX. For example, in Luke 4:17–18, when Jesus quotes Isaiah 61:1 and refers to restoring sight to the blind, that verse does not appear in the Hebrew version of Isaiah. It only appears in the LXX.

[8] The Hebrew Bible (or Tanakh) is the Jewish Bible. It is sometimes referred to as the Masoretic Text (MT), because the preservation and copying of the text was carried out between the 5th and 10th century by Jewish scholars known as Masoretes. Until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the oldest versions of the MT were found in thousand-year-old manuscripts such as the Codex Sassoon, Leningrad Codex and Aleppo Codex. Until 1947, scholars believed that the Hebrew text was older than the Septuagint, but they did not have Hebrew manuscripts that were older than the actual manuscripts of the Greek Septuagint. Although the New Testament sometimes quotes from the LXX, it is likely that it also quotes from the Hebrew text as well. For example, Matthew 2:15 quotes Hosea, “Out of Egypt I called my son.” The Hebrew text uses the word “son” (MT Hosea 11:1), while the Greek uses the word “children” (LXX Hosea 11:1). We will have more to say about this when we examine the Hellenising influence on ancient Israel in a future article.

[9] The deuterocanonical books are included in the LXX (Greek) but not in the MT (Hebrew). They are regularly found in old manuscripts and cited frequently by the Church Fathers, such as Clement of Rome, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Irenaeus, Tertullian, among others. They are the 7 books that are missing from the Protestant Bible mentioned earlier. The deuterocanonical passages refer to the Greek additions to the books of Daniel and Esther. St Jerome was probably the first Christian biblical scholar to notice the additions.

[10] Second Temple Judaism is the Jewish religion as it developed during the Second Temple period, which began with the construction of the Second Temple around BC 516 and ended with the Roman siege of Jerusalem in AD 70.

[11] Scholars have made the connection between the concept of canon and the concept of covenant: Cf. P.C. Craigie, The Book of Deuteronomy (NICOT, Grand Rapids, 1976 = 1979), p. 33, referring to RE. Clements, God’s Chosen People. A Theological Interpretation of the Book of Deuteronomy (London, 1968), pp. 89-105 (who dates the development of the principle of canonicity in relation to Deuteronomy to the late seventh century); cf. further R.E. Clements, ‘Covenant and Canon in the Old Testament’, in Creation. Christ and Culture (FS T.F. Torrance, ed. R.W.A. McKinney, Edinburgh, 1976), pp. 1-12.

[12] Suzerainty is a kind of treaty that includes the rights and obligations of a person, state, or other polity which controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state but allows the tributary state internal autonomy. The rights and obligations of the subordinate (vassal or tributary) are called vassalage, and the rights and obligations of a suzerain are called suzerainty.

[13] M.G. Kline, The Structure of Biblical Authority (Grand Rapids, 1972), pp. 27-110.

[14] Therefore the law was our schoolmaster to bring us unto Christ, that we might be justified by faith (Gal 3:24)

[15] This is why there is such a direct and intimate connection between the Word of God and the Body of Christ- both of which are the foundation of Holy Mass.