In this excellent article by Fr Paschal, we trace the fall from grace that has occurred in the most basic of human experiences: of being created either male or female. Far from being a post-modern invention, Fr Paschal explains that the post-modern imperative of control and subjugation of all things does arise as s rejection of Modernity, but rather is its logical conclusion. Gender dysphoria is a condition that requires genuine care and charity; our present day obsession with transgender ideology is an something that must be resisted.

In his strangely controversial book[1] When Harry Became Sally, Ryan T. Anderson defines contemporary attitudes to gender as a ‘Transgender Moment’, marked by unprecedented numbers of candidates for transition. At the same time, he identifies a cultural shift in attitudes towards gender identity, even within the medical field, reversing a previously-held hesitancy to intervene in these cases – not, as Anderson notes, on the basis of ‘new scientific evidence’, but on submission to ‘the pressure of ideology’.[2]

While Anderson is astute in his analysis of this moment in history, the gender ideology that is asserting itself so vigorously in contemporary Western society is not simply a contemporary problem. Rather, it has its roots in a gradual dismantling of the truth of the human person, that asserts itself most vigorously in existential and postmodern philosophy. The thesis is not novel. It has been argued convincingly in many and diverse studies.[3] This current essay is one more attempt to make some sense of a revolution that has enveloped us all.

The Rise of Modernity

The genealogy of gender is long. Post-Enlightenment modernity sought a more immediate foundation for knowledge than was professed by faith and mythology. Meaning and hope, which was once confided to God or fate, was increasingly placed within the sphere of the human capacity to know and act, and increasingly in a rationality that is the product of technical science. In this context, the German philosopher Eric Voegelin characterizes the whole of modernity as gnostic.[4] As Voegelin describes, Gnosticism is a program of demystification, consistent with the modernist cause of immanentizing reality: “an attempt at bringing our knowledge of transcendence into a firmer grip than the cognitio fidei, the cognition of faith, will afford”, and of drawing God “into the existence of man.”[5] This is attempted at various levels: (1) the intellectual, as a “form of speculative penetration of the mystery of creation and existence”; (2) the emotional, as a “form of an indwelling of divine substance in the human soul”; and (3) the volitional, as a “form of activist redemption of man and society.”[6] Each in its own way seeks a form of divinization, but in the absence of God.

Modernity’s immanentization of reality ultimately meant the eclipse of God in modern philosophy. The question of God, unable to find a foothold in the narrow constraints of positivistic verification, was, in Kant’s dispensation, relegated to a postulate of practical reason – noumenal, beyond the realm of human reasoning, but necessary conditions for the moral life.[7] The determination of what was good or evil was taken out of the hands of God and religion, dissociated from creation and the natural law, and was subject to human reason alone, whether according to duty (Kant) or the capacity to create happiness (Mill). This was given a subjective turn through the influence of Rousseau and the Romantic movement, with its focus on the self and authenticity, and expressed in morality of emotivism.[8] The seeds of a subjective autonomy had thus been planted.

The Postmodern Revolution

While postmodernism is typically presented as the rejection of modernity, intent on deconstructing its narratives of being, it might be more properly conceived as the victory of a nihilistic thread already present in modernism – a project that embraced the scientific method not only as a means of establishing truth, but also as a means of recreating reality.[9] From this nihilistic root, postmodernism emerged with its characteristic allergy to metaphysics, its abandonment of rational systems, its relativism and scepticism. It signalled “the end of the certainties and great stories” that typified modernism in its rationalist form, and ushered in “a more liquid concept” of being, including that of human beings.[10] While the predominant rationalistic branch of modernity sought a new human being based on the old, and achieved through a purification by reason, the nihilistic thread seeks a new human being through the transforming force of the will. While the former based the independence of the human person on the self-sufficiency of his all-knowing reason, the latter bases it on the autonomy of his will, a will that proposes its own truth.[11]

With the abandonment of metaphysics, the outlines of what is specifically human becomes blurred. It is emptied of any normative value. It is a blank slate on which nothing yet is inscribed. According to the existentialist branch of postmodernism, human beings are not defined by what they are, but by what they choose. According to Sartre, our choices define our essence, which is contingent on (and secondary to) our existence. There is no fixed design for how a human being should be and no God to tell us. Therefore, the task of defining ourselves, and our human nature, falls to us. Man is thus “condemned to be free” as Sartre writes; “because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.”[12] This burden of bearing our own identity and meaning renders the person in a constant state of uncertainty and angst.

With no defined purpose to life, the ultimate and only really serious philosophical question becomes, as defined by Camus, that of suicide. “Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.”[13]

Furthermore, with the ‘death of God’ (as proclaimed by Friedrich Nietzsche) man is freed from the constraints of a normative, created nature, and can so create himself. According to Nietzsche’s madman, having killed God allows human beings to move beyond their limitations. “There was never a greater deed,” writes Nietzsche; “and whoever is born after us will on account of this deed belong to a higher history than all history up to now!”[14] This ‘higher history’ is the not the reward of those who live according to their nature. It is not the prize prepared for the good and the just. Rather, it is the domain of the one who aggressively asserts himself against the herd mentality of the meek and obedient. It is the place of the Übermensch who pursues his Dionysian-like course of overcoming his humanity so as to create himself anew.[15] In its most radical form, this path is being tread by the so-called transhumanist or post-humanist project – a project of dissolving the human specificity, deconstructing human beings and attempting to create them anew; of wrestling humanity out of the hand of God or nature, and projecting it towards a new, man-made future.

Buoyed by an evolutionary philosophy that envisages our origins in chance, devoid of an originating reason or telos to which humanity is drawn, there is no ultimate reason why human beings should have evolved as they did; nothing special or final about their current form. Holding no claim on our allegiance, there is no moral imperative to continue as we are.[16] As the transhumanist philosopher Max More writes, our current form “is just one point along an evolutionary pathway and we can learn to reshape our own nature in ways we deem desirable and valuable.”[17]

Dissolution of the Body

In the quest for self-determination and realisation of desires, the body (especially in its sexual differentiation) is an obvious obstacle. Its givenness suggests a meaning that would limit our existential freedom. It is precisely for this reason that body, and especially its sexual characteristics, is the target for the elimination of constraints and difference. Thus sexuality and gender, as integral aspects of human nature, are subjected to the process of deconstruction. It too becomes a choice according to what ‘we deem desirable and valuable’.

Thus, according to postmodernism, the human sexualized body has no normative value. According to Michel Foucault, bodily sexual difference has no significance for personal identity. “Nothing in man – not even his body – is sufficiently stable to serve as a basis for self-recognition or for understanding other men.”[18] Indeed, the terms masculine and feminine themselves, victims to the deconstruction of language in which language has “ceased to represent the things it names”, have lost all transparency.[19] Thus, independent of the body, sexuality and gender are defined by orientation alone. In the words of American anthropologist, David S. Crawford:

“[T]he sexualized body has been drained of its intrinsic meaning and relationship to the person him- or herself. The person as such has been rendered essentially androgynous. Indeed, the sexualized body is only brought into the personal realm of desire, freedom, and love extrinsically by means of the fixing of an “orientation” – either through choice, immutable predisposition, or some mixture of these.”[20]

Following this logic, we are morphologically free to change the body and its phenotypical gender at will. Morphological freedom therefore becomes “an extension of one’s right to one’s body.”[21] It becomes the means of self-expression, realized “through what we transform ourselves into.”[22] As Anders Sandberg writes: “From the right to freedom and the right to one’s own body follows that one has a right to modify one’s body. If my pursuit of happiness requires a bodily change – be it dying my hair or changing my sex – then my right to freedom requires a right to morphological freedom.”[23]

However, morphological freedom, despite being couched in terms of self-expression, means that the body is no longer the irreducible basis of individuality and identity. The body does not have an essential relationship to the human subject. Instead, it is extrinsic to the person, arbitrarily related, redundant and replaceable.[24] With anatomy “no longer a destiny, but the result of a decision that is constantly revocable, the body turns into prosthesis of the Self that is forever in search of an identity. The body is now seen as a sketch, a draft to be corrected.”[25]

A new dualism is thus introduced into human beings. The body is something alien to the human person, superficial to his or her essence. It has no ontological significance. It can be changed liked clothes that are changed without touching on the person within. Of course, this alienation of the body does not begin with the gender ideology. It has deep philosophical roots in rationalist idealism and Cartesian dualism. But it reaches new and alarming heights in the current context, in which the boundaries “between what is given and what is the result of self-determination, between what is a technical product and what is properly human”[26], are dissolved. In the end, the category of what is distinctively human is itself surpassed: “a remnant of the past which is doomed to disappear.”[27]

A Christian Response

In the Christian response, the denial of human nature in its givenness does not constitute our exaltation and freedom, but our negation. Nothing good can come from the rejection of our created human nature and the inherent logic of our being. C. S. Lewis once prophetically referred to the abolition of man[28]: of the incarnated human person treated as an artefact, “as a mere ‘natural object’; … a raw material for scientific manipulation to alter at will.”[29] Lewis warned against this end, troubled by the prospect of human beings assuming ‘full control’ over themselves through such processes as eugenics, pre-natal conditioning, and by education and propaganda of a particular psychology.[30]

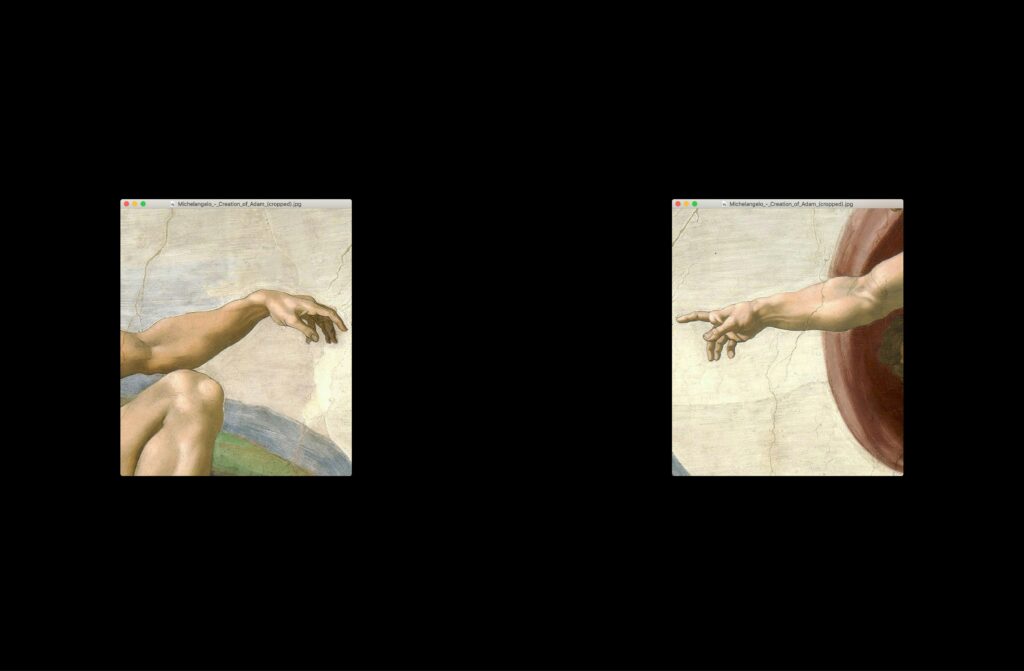

In contrast to the negative psychology that is inherent to gender ideology, Christianity offers good news for humanity – not the negation of the human person, but his or her affirmation and fulfilment. Humanity, in its sexual differentiation as male and female, comes from the creative hand of God – created in His image and likeness and proclaimed very good (Gen 1:26-27, 31). This creation in the divine image not only bestows a particular dignity to human persons, but also establishes an anthropological program that is normative for human flourishing. And our creation in sexual difference is fundamental to this program.

Created man and woman in the image of God – a God who is revealed as a God of relation in the Persons of the Holy Trinity – the human person is intrinsically gendered, and discovers in his or her body the way of being in communion with others. The body in its sexual differentiation is ordered towards the other – what John Paul II called the ‘nuptial meaning of the body’.[31] The gendered body, therefore, constitutes the means of sharing in God’s self-giving love and creativity. The body too shares in the divine image. It is not something extrinsic to soul and identity, but is the mediation of the person. The body is both informed by the spiritual essence of the person and informative of it.

The gendered body, therefore, comes to being with the person. It too is given, both as something received as gift and as something granted. As gift, the body in its sexual identity is received in gratitude and wonder. As granted, the gendered body is bestowed on us. It has defined content and meaning. It is expressive of the person and of their program. As anthropologist José Granados writes: “it is through the body that man perceives an original language, a language he has not created but is nonetheless interior to him, and that allows him to love.”[32]

Christian anthropology is, therefore, protective of what is given as something good and essential for human fulfilment. It is informed by a spirituality that does not regard categories of gift, acceptance, dependence and limitation as restrictive of the human spirit, but fulfilling of it. To illustrate this point, we recall the episode of Christ in which, in the midst of a discussion on human greatness amongst his disciples, the Lord brought a child into their midst saying: “Truly, I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Whoever humbles himself like this child, he is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven” (Mt 18:1-4).

Our Lord gives us the image of a child as constitutive of the greatness of human nature – of human nature as it finds it fulfilment in the kingdom of heaven. The child is one who loves to receive, who finds special delight in gifts and expressions of love, and who gives so freely in return. The child is one who is content in his or her need and dependence; who doesn’t see limitations as restrictive of his or her spirit, but allows every new discovery to be a source of wonder and delight. The child is also one who is comfortable in his or her own skin; who has not yet felt the angst of comparison or the expectations of the world at large.

Formative of an anthropology, this image proclaims that human fulfilment and true greatness is found in the mystery of our creation in dependence, communion and love. It sees the givenness of our being as reflective of the truth of our nature that must be embraced and lived. Such acceptance of the givenness of our nature is also a powerful antidote to gender ideology with its rejection of the given. It unmasks the viciousness of the gender ideology especially when inflicted on those who are most vulnerable in our society. Indeed, the very ones who are proclaimed great through their unfettered capacity to love, accept, and live in dependence – that is the children that Christ sets before us as an example – are now the targets of gender theory: stripped of their innocence and thrust into the Dyonisian-mould of creating themselves; of rejecting nature and asserting themselves against that which is given. This truly is a tragedy – the reversal of all that is good.

The image of the child is also representative of all those who are vulnerable. In this context, we must recognize that people with gender dysphoria are often quite fragile, bearing the wounds of internal conflict and alienation from their bodies, as well as the misunderstanding and alienation from others. They demand our compassion. They need our care – our accompaniment, our listening ear, our prayers. But they also need our wisdom – that accepts the goodness of what is given; that does not negate nature; that rejects the dualism inherent in gender ideology, and helps those who suffer to be at home in their bodies. It is a wisdom and compassion that unmasks the lie of unfettered freedom and seeks wholeness in truth.

Conclusion

In this brief genealogy of gender, we see how the internalization or subjectification of reality has taken hostage of our understanding of human nature. Western culture has succeeded in liberating itself from the givenness of creation and nature, to bask in the so-called freedom of self-determination. When applied to sexuality, it has become manifest in the elimination of difference and the fluidization of gender. Christianity, on the other hand, with its affirmation of a loving Creator, offers an alternative anthropology that roots human beings in their created nature, variously distinguished by features of dependence, solidarity, relationality, uniqueness, and transcendence. The gift of our being, incarnate in a gendered body, is received in gratitude. The words of the Creator that proclaimed this way of being as ‘very good’ must echo throughout the ages. Indeed, only from this starting point can we respond adequately to the question of gender that is put before us today. Only from this point can we protect the children and vulnerable in society. For, as the American bioethicist Leon Kass writes: “Only if there is something precious in the given – beyond the mere fact of its giftedness – does what is given serve as a source of restraint against efforts that would degrade it.”[33]

[1] See Ryan T. Anderson, “When Amazon Erased My Book,” First Things (February 23, 2001). https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2021/02/when-amazon-erased-my-book

[2] Ryan T. Anderson, When Harry Became Sally: Responding to the Transgender Moment (New York: Encounter, 2019), 2.

[3] See especially Carl R. Trueman, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism and the Road to Sexual Revolution (Wheaton IL: Crossway, 2020); Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay, Cynical Theories: How Universities Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity – and Why This Harms Everybody (London: Swift Press, 2020).

[4] Eric Voegelin, The New Science of Politics: An Introduction (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1987), 133.

[5] Voegelin, The New Science of Politics, 124.

[6] Voegelin, The New Science of Politics, 124.

[7] Immanuel Kant, Critique of Practical Reason (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2002), Book 2, Chapter 2 [IV and V], 155–67.

[8] See Carl R. Trueman, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, 125: “Rouseau lays the foundation for expressive individualism through his notion that the individual is most authentic when acting out in public those desires and feelings that characterize his inner psychological life. When he would not have anticipated how this would later manifest itself, this construction of selfhood and human authenticity is the necessary philosophical precondition for modern identity politics, particularly as it manifests itself in the sexual politics of our day.” See also Alisdair MacIntrye, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theology. 2nd ed. (London: Duckworth, 1985), 11-12.

[9] Luis Miguel Pastor and José Ángel García-Cuadrado, “Modernity and Postmodernity in the Genesis of Transhumanism-Posthumanism,” Cuadernos de Bioética 25 (2014), 340.

[10] Luca Valera, “Posthumanism: Beyond Humanism?” Cuadernos de Bioética 25 (2014), 482.

[11] Pastor and García-Cuadrado, “Modernity and Postmodernity in the Genesis of Transhumanism-Posthumanism,” 340.

[12] Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism and Human Emotions (New York: Philosophical Library, 1957), 23.

[13] Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus (New York: Vintage, 1983), 3.

[14] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), Book 3 [125], 120.

[15] Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006),Part I [3], 5. Several critics make this parallel, e.g., José Ignacio Murillo, “Does Post-Humanism Still Need Ethics? The Normativity of an Open Nature,” Cuadernos de Bioética 25 (2014), 471; Elena Colombetti, “Contemporary Post-Humanism: Technological and Human Singularity,” Cuadernos de Bioética 25 (2014), 368. Bostrom, however, denies a direct link with Nietzsche’s thought. Nick Bostrom, “A History of Transhumanist Thought,” Journal of Evolution and Technology 14 (2005), 4.

[16] John Harris, Enhancing Evolution: The Ethical Case for Making Better People (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 39.

[17] Max More, “The Philosophy of Transhumanism,” in The Transhumanist Reader: Classical and Contemporary Essays on the Science, Technology, and Philosophy of the Human Future, edited by Max More and Natasha Vita-More (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 4.

[18] Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, genealogy, history,” in The Foucault Reader, edited by Paul Rabinow (New York: Pantheon, 1984), 87-88.

[19] Marnia Lazreg, Foucault’s Orient: The Conundrum of Cultural Difference, From Tunisia to Japan

(New York: Berghahn, 2017), 98.

[20] David S. Crawford, “Liberal Androgyny: ‘Gay Marriage’ and the Meaning of Sexuality in Our Time,” Communio 33 (2006), 257.

[21] Anders Sandberg, “Morphological Freedom: Why We Not Just Want It, but Need It,” in The Transhumanist Reader: Classical and Contemporary Essays on the Science, Technology, and Philosophy of the Human Future, edited by Max More and Natasha Vita-More (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 56.

[22] Sandberg, “Morphological Freedom,” 59.

[23] Sandberg, “Morphological Freedom,” 57.

[24] Valera, “Posthumanism: Beyond Humanism?” 485.

[25] Maria Teresa Russo and Nicola Di Stefano, “Post-Human Body and Beauty,” Cuadernos de Bioética 25 (2014), 459.

[26] Russo and Di Stefano, “Post-Human Body and Beauty,” 459.

[27] Murillo, “Does Post-Humanism Still Need Ethics?” 471.

[28] C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (New York: Harper Collins, 2009).

[29] Lewis, The Abolition of Man, 73.

[30] Lewis, The Abolition of Man, 60.

[31] John Paul II, “General Audience,” January 9, 1980. https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/audiences/1980/documents/hf_jp-ii_aud_19800109.html

[32] José Granados, “The Body, the Family, and the Order of Love: The Interpretive Key of Vatican II,” Communio 39 (2012), 208.

[33] Leon Kass, “Ageless Bodies, Happy Souls: Biotechnology and the Pursuit of Perfection,” The New Atlantis 1 (2003), 20.