This week we are re-printing an article from almost twenty-five years ago that appeared in our journal in June 2002. Nearly a quarter century has passed since its publication- yet it is surprising just how relevant it is to our current situation. Certainly, some of the banner headlines have changed- but not the underlying problems which this article so carefully examines. Next week we will have the second part of this article explaining to our readers why traditionalists need to be prepared for the long game and exactly how they should play it.

The crisis in the Catholic Church throughout the English-speaking world, which has been triggered by a stream of sexual abuse scandals, would not come as a shock to any commonsense reader of the Church’s history since the Second Vatican Council. The only people who would have been stunned by these events are those who have been deaf and blind to the real story of the Church these last 40 years.

It is not enough, however, to focus on the proximate cause of the sexual abuse phenomenon: chiefly, the presence of predatory homosexuals in sacristy and confessional box; a type which has been protected and cosseted in many Catholic seminaries and religious communities, and against whose activities and unfitness for the priesthood and religious life no word could be said to bishop, rector, or superior. This is to consider the problem too narrowly. The issues go deeper and their implications extend far beyond the field of sexual morality.

Sexual sins, including homosexuality, among clergy and religious are not new. And the failure of Church authorities to do their duty in the face of corruption, of whatever kind, has a long history. Reform is usually forced upon the Church by crises, rarely by long-sighted and courageous bishops. In reacting today to a crisis which they yesterday denied, the bishops of the United States of America, and elsewhere, are performing to par for the historical course.

Modern Manichees

What is primarily at stake here is neither the flourishing of vice nor the failure of leadership. What is at issue is something that, at first hearing, sounds strange to the modern ear and apparently contrary to experience. The problem is denial, fundamentally, of the goodness of matter – including the human body – and an assertion that ‘purity of spirit’ or ‘purity of intention’ is the ultimate good and rule of life. It is a new form of an old Manichean idea. To put it in the vernacular, “it’s not what you do, but how you do it.” This doctrine came into the open after World War II and spread rapidly in Catholic communities and institutions from the Vatican Council onwards. As opposed to what was actually taught in official Church statements, this was what was commonly preached on the ground. It is today one of the defining beliefs held by Catholics throughout the western world.

There are two areas where this teaching plays a crucial role. One, obviously, is in the field of human sexuality. The other, less obviously, is in that of worship. The two, however, are related.

It was not long after Vatican II that school children in the senior years, or young adults attending pre-marriage courses, began to hear that the key thing about sexual relations was not acts so much as the sincerity, freedom, respect, and love with which they were done. People often went to considerable lengths to avoid stating explicitly that particular sexual acts – fornication, adultery, masturbation and sodomy – were always objectively wrong or contrary to the order of nature. This notion of what we might call ‘sex with attitude’ was commonly reinforced in the confessional where, in addition, it was frequently whispered that the pill was OK.

Body Exultant

In a culture that claimed to exult the body, the very opposite happened with the blessing of many a Catholic teacher and confessor. Bodily acts were reduced to an indifferent value: what counted was the disposition of the human spirit that assented to them. What we have here is the human spirit or soul as arbitrary ruler of the body; a tyrant, indeed, over the whole man. Once this shift has been made on the level of thought, then the body becomes, willy-nilly, unholy and any act is permissible. Here we have the intellectual root of the revolutionary sexual culture that prevails outside the Church and exerts so powerful an influence within it, not least among some of its clergy.

It would be wrong, however, to point the finger solely at vicious priests and impotent bishops. Certainly, they have much to answer for. But in the midst of the finger wagging, outrage, and shame, the whole Catholic people of the western world might ask itself this: how far do we act on the same premises? There would be few of us who could honestly say that we had never absolved ourselves of many things (sexual or otherwise) because we were ‘pure of heart’, ‘sincere’, or ‘well- meaning’. The forgiveness – or denial – of our own sins, is the perennial temptation of men, though today it is a mass and public cultus from the practice of which few of us could claim to be free.

Here we turn to the liturgical issue, a move that would seem incongruous to many modern Catholics. Yet the problem must be posed: who can enter the temple of the Lord, let alone approach His altar, if he has not first admitted his sin?

Angelism

To grasp the dimensions of the issue, we must first understand what liturgy is. Liturgy is the form in which men worship and it is an act not only of the spirit but also of the body. It is an act that, by its nature, engages material things. At least while ever the world lasts, we can confidently say that a liturgy that does not engage material things – or which seeks to disengage from them, or diminish their role, or to employ them any which way – ceases to that extent to be an authentic act of worship. To put it in other terms, if we try to worship in the manner of angels, our worship is no longer human.

Here then is the doctrine of ‘purity of spirit’ and its consequences. When one is worshipping “in spirit and truth” there is no need, so the argument runs, for sacrifices or oblations let alone for ritual acts or sacred things and places. It is the heart that counts: “A humble and contrite heart, I will not spurn.” Official teachings on the nature of the Mass notwithstanding, Catholic worship as it is actually practised in the Western Church tends, all to commonly, toward a congregation of the righteous. ‘Liturgy with attitude’ is the ruling norm.

Things Foreshadowed

As in the case of disordered sexuality, we see in the disordered liturgy of the West signs of the imperious human spirit at work. She lords it over things arbitrarily and refuses to admit their intrinsic merit; so proud she is that she cannot grasp the distinction between the use and abuse of things. It is a spiritual deformity all the more terrible because the sacrifice and oblation of the Mass are not, as in the Old Testament, the shadows of things to come, but the very things foreshadowed. In the Mass we have the actual pure and spotless victim, the long awaited and sole efficacious outpouring of blood which washes us clean, once and for all, made present upon our altars: a fact as material as bread and wine, as stone and wax, flame and incense. The problem then for would-be worshippers in “spirit and truth” Anno Domini is not only that hearts must be pure, but also that they must be ready to deal with God in public worship through the material forms of the one and only true sacrifice.

In the Mass it is not only the spirit, but also the matter that matters. It is thus for the whole of human life. He who denies it in one place will not easily resist the intellectual imperative to deny it in another. It is not surprising therefore that the liturgical revolution hit the Church at the same time as the sexual. If we hold matter cheap, then we must ask ourselves whether we are fit to enter either God’s temple or the temple of another’s body.

Even in the field of church government, the connection between the sexual and liturgical revolutions endures. The same episcopacy which denied the corrupting influence of the sexual revolution upon the teaching and practice of the Catholic clergy, also denied the liturgical revolution over which they presided and its consequences. Being “in denial” has been, indeed, the defining mark of the post-Conciliar pastorate. Whether it has been emptying pews or the dogmatic trahison des clercs, declining vocations or the collapse of Catholic identity, there is not one pathology that has afflicted the Church during their watch that this generation of First World bishops has not at one time denied. And, if the disappearance of the confessional queue is any indicator, we, the Catholic people of the West, have followed, in the case of our personal pathologies, the example of our shepherds.

In a time of great crisis the practical question is what to do about it. Again, there is no mystery here. It has been both obvious and ignored throughout the whole of the Great Leap Forward of the post-conciliar era. It is to preach the truth “in season and out”: to preach about sin, repentance, forgiveness and the God of mercy; and then to repent, to forgive, and to make reparation: pope, bishops, priests, and the whole Catholic people.

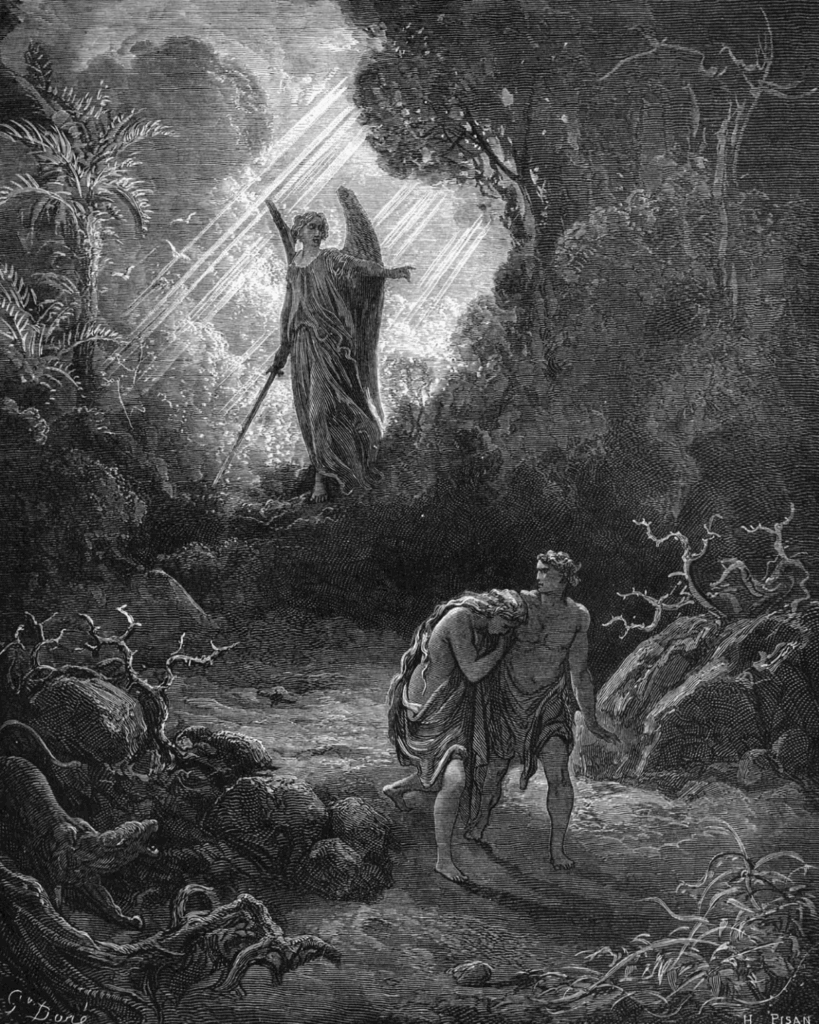

We must, however, approach the solution realistically. For a Catholic Church that can apologise to powers, peoples, and religions for past sins real and imagined, to apologise to God for the last four decades of betrayal will not come easily. Perhaps in the end we shall be obliged to adopt the words of Pascal as the epitaph of the modern Church and of the world it failed: “Man is neither angel nor beast, and his misfortune is that he who would act the angel, becomes the beast.”