Many today who either remember something of the ‘old days’, or who have read about them, wonder how it is possible to have come in such a short time from a Church that has a clear vision of who she is, of what she is meant to do and how she is to teach the faith, to a Church that does not seem to know why she exists at all and is incapable of preaching it with clarity to the world. In recent articles, I have referred to the mentality that has led many people in the Church to a presentation of the faith that, at its very best, is confusing. One pays lip service to the defined dogma of the faith, but then one proceeds to say that it is perfectly fine not to believe it or live according to it. In some cases, even the past is rejected as no longer relevant at all. How in the world did we come to this? It is one thing to decide to leave a Church in which one no longer believes. It is quite another to make that Church out in your own mind to be something completely different, and to seek to change the institution so that it fits your own personal vision. While there is certainly no quick answer to the question of how this happened, I will attempt to explain what, in my judgment, is its principal cause, namely what St Pius X called the heresy of modernism, which is still very much alive and the cause of many errors today.

Most Catholics have probably heard the word modernism. Those who haven’t would imagine it has something to do with living in modern times, and in this, they would not be wrong, though it would hardly be sufficient to define the term. Pope St Pius X set out, in the encyclical Pascendi Dominici Gregis (8 September 1907), to explain exactly what modernism is. Few today have read this major magisterial text, which admittedly offers a challenge to most readers. To simplify the matter in layman’s terms, let’s say that St Pius reveals three fundamental beliefs of the modernist mentality upon which is based the entire complex thought system of every true modernist. These three beliefs are evolution, agnosticism and immanentism.

A Triple Whopper

When we say that the modernist believes in evolution, we are not talking specifically about the hypothesis of the evolution of species as expounded by Darwin and his disciples. More often than not, however, if someone is imbued with modernist thought, there is little chance that he will oppose the evolutionary hypothesis, for it fits in quite tidily with his own mindset.1 What is that mindset? Quite simply, that all things are in perpetual motion, nothing is stable. Since man moves within this perpetual motion, he too is unstable, evolving both physically from a zygote to old age and mentally, migrating through a variety of intimately held views that can and do change throughout his life.

Furthermore, for the true evolutionist, everything evolves, and so God too, if He exists, must evolve, and if God evolves, then there is nothing definitive we can say about Him. It is not difficult to see how such thinking is incompatible with a faith that believes in a God who is absolutely unchanging and who, therefore, has inspired dogmas that are just as immutable.2 To believe in evolution is to already be leaning toward modernistic theology.3

Agnosticism professes that we cannot have certain knowledge of anything beyond the impressions made on our senses by material reality, and even this only creates impressions that we cannot fully trust. This frame of mind stems directly from a number of modern philosophers, beginning with René Descartes, who closed the gate to objective reality, positing that everything existing outside the mind is mere extension or res extensa, with all other perceived attributes as figments and constructs of the mind. His disciples have struggled ever since, without success, to anchor the mind to something that is not ephemeral. All modernists, in particular, follow this same thought experiment to some extent in which they doubt their senses and turn in on themselves, holding fast to the one thing that seems most true to them: ‘I think, therefore I am’ – cogito ergo sum. The point is that, if we cannot know anything for certain, neither can we know anything about God. Any knowledge we have of God is going to depend on the way we view reality, and that is a very personal matter; there are going to be as many views as thinking persons.

Now, if man has been locked out of or at least doubts the knowledge of the reality that is beyond him, life can become very bitter indeed. All there is to live for are physical pleasures, futile amusements and the hope of material success. For the person, however, who does not want to remain in the sphere of the brute animal, one must imperatively find some other source of truth that gives meaning to his life. Since the modernist believes that all is evolving and that we can’t know anything for sure, the only source of truth that can offer him something to depend on is, well, you guessed it: himself. This is the third whopper, what St Pius X referred to as vital immanence, that attitude by which one ‘believes’ because one ‘feels’ that some things are true as opposed to others which one ‘feels’ to be false. The quasi-omnipresence of this mentality in the modern world is all too obvious. Such are the pillars upon which is built the modernist worldview, which has virtually taken over the Church.

You Have Your Truth, I Have Mine

When it is applied to the realm of the Catholic faith, we come up with some very odd things indeed. For example, the ‘Catholic’ modernist, when asked if Jesus Christ is God, will be quick to say: ‘Well, of course Jesus is God! This has been settled by the First Council of the Church.’ By this, he means nothing more than that a group of individuals in the first century met a man named Jesus whose knowledge and power they could not explain. Their experience of this exceptional man led them to ultimately think that he was something more than an ordinary man. Pondering their experience ultimately led them to deify this man, that is to say, they made him out to be God. This experience of a group of people then spread to others, and finally, as the number of people who felt Jesus was God continued to grow, he was finally proclaimed to be God at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. And voila, Jesus is God!

Based on this sort of reasoning, the modernist is convinced, even if he himself would not know how to formulate it, that ‘truth’ is something that we arrive at because a number of people come to the same conclusion about any given topic. But since people and times change, there can be no definitive truth; truth changes with them. All we can have are ideas that predominate and help us formulate our identity in any given age; such, for the modernist, is the role of organised religion, and for the Catholic, that of the Catholic Church.

This explains why it is that today we can have so many Catholics who think not only that dogma and the moral teachings of the Church are not binding, but even that they can change. Since they can change, they will of necessity change someday. Until that day, we have every right to play fast and loose with them. When questioned, the more informed of them will say that what the Church has always taught is there to guide reflexion in a certain direction, but nothing prevents us today from coming to a conclusion opposed to that of our ancestors, especially due to our supposed greater knowledge of humanity and the sciences. The Catholic Church becomes, according to this mentality, a body of people who have made similar experiences and come to similar conclusions about what we should think about God and about how to live together. That’s it. Nothing more. Modernists are convinced that we cannot really know anything with absolute certainty. ‘Truth’ evolves over time. Each person ultimately makes up their own criteria for what is ‘true’. Is true whatever I deem to be true. Is true whatever is useful for me here and now. If tomorrow it is no longer useful or if it can no longer be understood due to changing circumstances, then it ceases to be true. This explains how modernism is so devastating to any belief system and why St Pius X singled it out as the gravest danger ever to the faith, the ‘synthesis of all heresies’. Indeed, all other heresies deny one or other aspect of the faith. Modernism attacks its very essence, declaring that there can be no unchanging faith, but only personal feelings that can and must evolve. At the same time, the modernist will never leave the Church; he will stay in it in order to help it ‘progress’. And there you have the reason why so many today who call themselves Catholic have ceased to be so.

Old Tunes to a New Pitch

Coming back now to the question we began with, how does this help us understand what is going on in the Church in the present day? As one of the ancient hymns of the breviary tells us, we must pray that fraudis novae ne casibus nos error atterat vetus, which we can translate as lest some deceit or wile of ancient error should beguile us anew. In other words, we pray that ancient errors may not lead us astray by means of new deceptions. The devil is always playing the same old tunes, much like a broken record, but he likes to play them on a variety of pitches and with diverse instruments, to suit the taste of all, in order to deceive the unwary.

Many today fall for a false idea of evolving reality that leads them to think, if not to say, that there is nothing stable. What was bad yesterday may be good tomorrow. What is good today may be bad tomorrow. Typical of this is the way some in the Church consider ancient forms of liturgical prayer to be dangerous for today’s Catholics. This explains what so many people, both within and without the Church, find incomprehensible: how can a prelate want to ban the Traditional Latin Mass, which our ancestors prayed for centuries and is one of the most sublime forms of prayer man has ever been given? Quite simply because the modernist is convinced that today there are enough ‘enlightened’ people who have moved on from that, and that the Church herself must now move on, under pain of being ‘stuck in the past’ – the horror of horrors for the evolutionary mind! If everything evolves, so must our prayer, so must what we call the Church.

The same happens with the moral teachings of the Church. To take an example, up until very recently, no Catholic in any country would have questioned that the death penalty in certain cases is not only justifiable, but is even a virtuous act of justice and charity, based on God’s revelation and on the natural law.4 Nowadays, many Catholics view capital punishment as a mortal sin in every case, equivalent to murder. Now, if something everyone thought was good is now bad, people will quickly conclude that things we thought were bad will someday be good. Consider the growing number of Catholics who find no issues with contraception and sodomy, not to mention abortion and euthanasia. The only way to explain such reversals is that nothing really is stable, nothing lasts, and all that matters is what people feel at a given moment in time.

tegrity.

A New Conscience

Furthermore, this mentality leads people to think that since there is no transcendent truth, and since we all have our own convictions thanks to vital immanence, other people have theirs that are just as respectable as ours. We must therefore strive to get along as best we can with mutual respect, even when they come to conclusions opposed to ours – whence the importance of inter-religious dialogue and ecumenism. While the true Catholic knows he must be tolerant of others, he also knows that they are wrong and will attempt to lead them to the truth. The modernist Catholic, however, has no problem with saying that Jews and Muslims and anyone else who rejects the divinity of Christ can be just as right and good and holy and pleasing to God as one who holds the divinity of Christ to be the very foundation of justification. Why? Because thanks to vital immanence, there is really nothing you can say to convince someone of the error of their ways. ‘I feel what is true in my heart, and so you have nothing to teach me’. Ultimately, there is no error, other than not being true to yourself and your own feelings.

This is also why the concept of conscience has changed. In the Church’s traditional teaching, the individual conscience is not the supreme norm of the morality of any action, but its proximate norm. One must make moral decisions based on the moral knowledge available; this is true. But this moral knowledge must be sought out, it must be learned; the conscience can only make a proper judgment if it has been given the means to know what is right and wrong. That is to say that one must first form one’s conscience before following it. Nowadays, however, most Catholics consider that whatever anyone thinks is right is right for them today (though it may be wrong for them tomorrow), and they refuse to acknowledge that there are absolute norms always and in every place inviolable. But how can they forget such a fundamental point? Quite simply, because they do not think there is any absolute. All evolves, all changes, all that remains is me, and therefore I do what I feel like doing. To be sure, few would formulate their convictions so brazenly, but it is indeed the mentality that reigns. It is the modernist in each of us, and that modernist goes all the way back to the Garden of Eden.

The Remedy for a Disease of the Mind

The sin of our first parents, who believed the Serpent and sinned against God, was essentially that they preferred their own judgment to that of reality, that of God. The modernist notion of vital immanence was already present in the Garden, and it is what led Adam and Eve astray. Ever since then, history has been one long effort to find our way back to the primeval experience of receiving all things from God and living at peace in His world, rather than creating our own little ‘paradise’ on earth in which what we feel matters. There is a modernist in each of us, and every time we find ourselves wanting to adapt reality to ourselves, we are modernists.

After this intentionally succinct attempt at penetrating the mind of the modernist, a question might arise. Is there a solution to this disease of the mind? Is it possible to find a way out of the labyrinth of evolving ideas that, in our present state, revolve around our personal tastes and desires?

For the humble soul, there is always a solution. And in saying that, we have already given part of the answer. Modernism, like original sin, is born of pride, love of novelties and self-will, the conviction that the good is what suits me, what I happen to like. If a person can acquire enough humility to realise that they are not the centre of the universe, that reality does not revolve around them, they have a chance of reform.

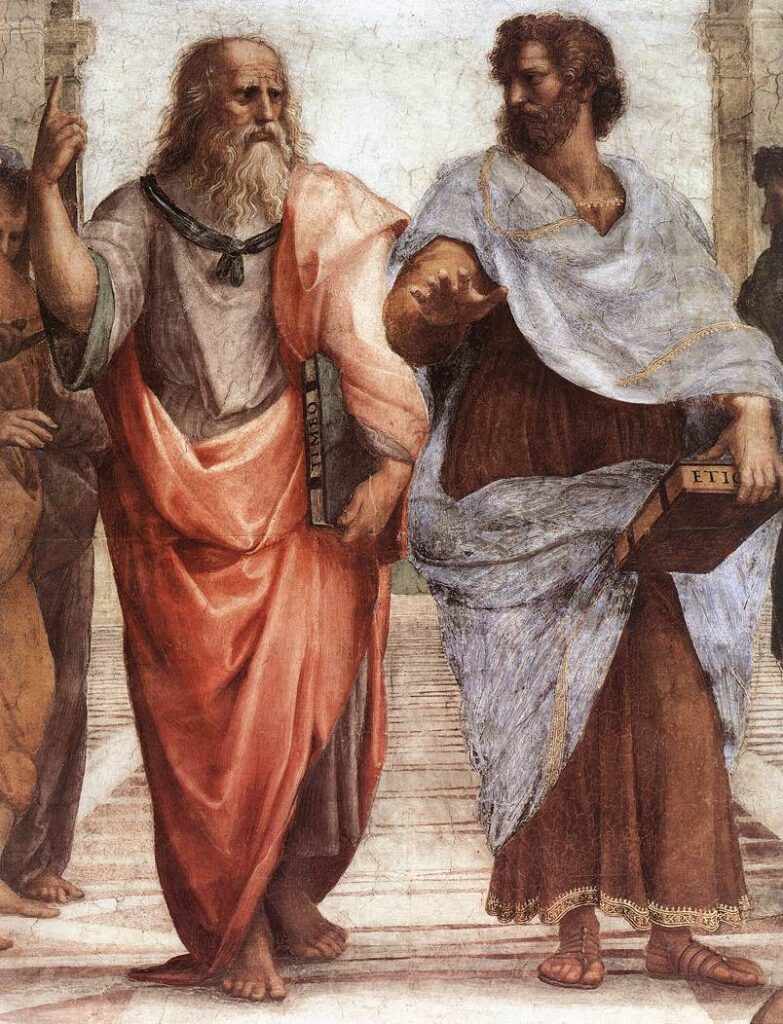

In our history, we have numerous examples of upright souls who knew how to anchor their lives in solid, enduring, unshakable truth, even before the advent of Christ. In particular, the Greek philosopher Plato had already understood the problem and found its solution. He knew there could be no transitory world if there were not a world of the absolute, which he called the Forms or Ideas. He also knew by keen observation that the principle of life in man, the human soul, is of its very nature immaterial, that is to say, it is not dependent on matter to exist and therefore will live forever; it is immortal. Anchored to these two realities, which the Christian tradition calls God and the Soul, the mind can soar far above the lowly contingencies of a fleeting existence and find the essential purpose of life. It can cease being tossed to and fro on the tempestuous sea of the ever-changing whims of its own ego. It can cease being a modernist.

- Indeed, one can say that modernism may never have developed as a system at all without the work of Darwin. ↩︎

- Cf. e.g. the beginning of the Constitution De Fide Catholica of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215): ‘Firmiter credimus et simpliciter confitemur, quod unus solus est verus Deus, aeternus et immensus, omnipotens, incommutabilis, incomprehensibilis et ineffabilis…’ (DH 800). ↩︎

- I use the expression ‘believe in evolution’ intentionally for the simple reason that to this day evolutionists have still not given us any coherent proof of their hypotheses, nor have they answered the growing number of objections that point to young earth creation. But this would take us too far from our present subject. ↩︎

- Cf. among many others Gn 9:5-6; Ex 22:12, 18; Lk 23:41; Jn 19:10-11; Acts 25:11; Rm 13:4; cf. also St Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, IIa-IIae, q. 64, a. 3, as well as the magisterial acts of every single pontiff who has spoken of the matter up until Pope Francis and every single catechism until Pope Francis changed the Catechism of the Catholic Church. ↩︎