Introduction

We come to our twelfth and final lesson in this series. At least for now. We have said many things about the Tradition; and I pray they have been of benefit to all of you who have made it this far. You have perhaps wondered at different moments during this series, what point I was going to make; and if I was ever going to make it. Much of what I have written in this series is me thinking out loud whilst trying to answer one very complicated question: what is the Church’s Tradition? And in order to answer that one question, there are many other questions that pop up along the way. We have covered nearly twenty centuries of Christian doctrine, theology, history, philosophy and culture. In a word- the Church’s Tradition. We have now come to the point where we have to draw some conclusions about what we have said and what, if any, path forward we can take. For one of the tasks I set for us right at the start of this series, is to understand whether something as ancient as Christian Tradition could shed any light on Catholicism’s present malaise.

We are at the end of something. Both within the Church and the secular culture. This is why there is so much uncertainty at present in the world. In the West, we have never been richer, fatter and unhappier than we are right now. We have every reason to be thankful for the material benefits we enjoy. But the truth is, that underneath our prosperity, we are spiritually and morally adrift. And this weighs on our conscience more than our material wealth uplifts our spirit. Future generations will most likely marvel at both our creativity and our folly. How could a generation that solved so many material problems actually be so spiritually impoverished?

The post-World War II secular progressive agenda that has dominated the culture has played itself out- and we have no idea about what will come next. That is why there is so much uncertainty hanging in the air. And this uncertainty brings anxiety with it. We have lost faith not only in the institutions of the West- democracy, free markets and the rule of law- we no longer cherish the ideas that stand as the foundation of these institutions- the imago Dei and the redemption of all mankind. This crisis of confidence also infects the Church. However, the Church has a sure and guiding light that can show us what to do in order to find our way back. The difficulty is, we have done everything possible to ensure that this light will not shine.

One thing is abundantly clear in the Church- Tradition has won the argument for what will renew Catholic life. Despite the open hostility, the absence of appreciation amongst the hierarchy and the minority of its following within the faithful; it is abundantly clear to anyone that the Church’s Tradition is the only way forward. Every other alternative has failed. Whether that was the liberal project which believed a radically less catholic church would be a vastly superior church; or the rather hopeful yet somewhat naive project of “orthodoxy alone”, which thought that good doctrine by itself would fix things. Both have not brought the renewal they promised. You cannot right the ship by trying to make peace with the world. And neither can you do it with a little bit of catechism and a lot of personal piety. There is only one way forward- and it is the same path that the Church has walked for twenty centuries: the Tradition.

But in order for us to draw this conclusion, we require an explanation of how all we have said fits together, for it is not perhaps as obvious as it needs to be. You may have had the impression over the last eleven lessons that I have been a bit random in my choice of topics. Although they may seem eclectic, they are anything but haphazard. As I have said before- there is some method to my madness, but there is always a little madness in my method too. The method however, needs to be teased out a little more in order to make sense of these lessons. This is how we will end this series.

The Constant Temptation in Four Moments

You have, I hope, noticed that all throughout this series I have used a number of different definitions for the Tradition. They have each been deployed at different times in order to highlight the complexity and depth of a notion that is often pigeonholed into a somewhat watered-down category. Many Catholics will tell you that Catholic Tradition consists in the unwritten truths of revelation. They are not wrong- but if left unexplored and unexplained it creates a false dichotomy between written and unwritten revelation: Scripture and Tradition. All of Christian revelation was oral in its origin (Mt 4:17; Luke 4:17-18)- some of it was written down for our instruction (John 21:24-25). There is no conflict between them. What we must understand is how and why this revelation has been handed down to us. For in this understanding do we discover something precious about the Christian vocation.

First moment

The great temptation for each generation is to take the Tradition of the Church for granted. And this we can do in a number of ways. The first way, is that we fail to appreciate how much work it takes to hand on the treasure that is Christianity. Every generation wakes up into a world that has been handed to it. And so whatever world we wake up into is the norm. I take the normal for granted, precisely because it is normal to me. The same applies to the Christian world as well. It seems completely normal to me that the Holy Spirit is divine, Christ has two natures and that the Bible is composed of 72 books. But as we have discovered, that was not always so clear and obvious. Arguments about these issues raged for the first few centuries of the Church’s life- and it took saints and men of great learning to figure it all out for us. This is a reason for why the “orthodoxy alone” approach was destined to fail- it takes doctrinal orthodoxy for granted, whilst eschewing the delicate and intricate process that defined what orthodoxy is- the Tradition.

That is why we opened this series examining the origins of Scripture. But not just the textual origins of Scripture- which we only briefly mentioned- but rather the idea for the concept of Scripture itself. From whence did the idea for a New Testament emerge? It seems completely normal to every Christian that the New Covenant should possess a New Testament- but from where did this idea originate? Who decided that it should be written, who should write it and what books it should contain? We have no direct instructions that answer any of these questions; yet we are certain of the results. And so, we have to look to something else that makes sense of the things that we take for granted.

And this is where we encounter the first of several definitions that I have given for the Tradition in this series: it is received wisdom (Lessons II-IV). Aquinas when teaching about the importance of definitions in his philosophical work, highlighted the importance of two things: firstly, a definition must capture the essence (nature) or truth of a thing; and secondly, that essence (nature) is known to us by its properties and functions. Put simply, to know what something is means to know what something does. And that is how we begin to understand the Tradition of the Church. The first thing that we notice is that all tradition is something received- but it is not just anything that is received, for there are many things that are handed on that should be left behind. There is something entirely unique about what is received as Tradition; and this uniqueness is captured in what tradition does. Let me explain.

The Christian religion, although divinely willed is not centrally planned. By not centrally planned I do not mean that we are blindly making it up as we go along or that there is no authoritative hierarchy. Rather that the life of the Church unfolds and develops as a response to Divine Action. There is truly at the heart of Christianity a life (John 10:10); and like every life, it must grow and develop. And it grows according to the Divine Will, not according to set of algorithmic instructions as dictated by the Almighty. Without getting into the weeds of this discussion, for it is as complicated as it is interesting, suffice it to say that the Lord did not come to tell us just what to do; rather He came to call us his friends (John 15:15). And this friendship is a relationship with Him, not a set of directives from Him. But in order for us to have a relationship with Him, requires that we know some truths about Him. This is why Christianity stresses the reasonableness of our religion: since you cannot love what you do not know; and you cannot know what is unreasonable. In order to have a friendship with God requires that what we know about Him be reasonable to us. And this is why we introduced the first definition of the Church’s Tradition as received wisdom. For the tradition is not just information we receive about God- we receive something of the very life of God Himself. Hence it is a treasure that we know to be Wisdom itself.

Second moment

The second thing that we take for granted is how different our Christian religion is from the Jewish religion from which it emerged. After nearly twenty centuries of separation, this distinction no longer appears relevant to us. However, even though the distinction is clear, the reasons for it are not. And they still matter a great deal. This is why we then turned our attention to the question of Gnosticism. Gnosticism preyed on the fact that Christianity would be a religion of grace not of law. But this principle never meant that Christianity would be a lawless religion, rather that the law would not make us right with God. Being made right with God required not just a re-jigging of our behaviour but a re-birth of our life from above (John 3:3). How this was to play out in the Christian life life became one of the first struggles of the early Church.

In order for us to enjoy this friendship we must have some idea about how to conduct this friendship. In what does friendship with God consist if there were no strict rules to observe? If dietary practices and ritual purity were not the foundation for a friendship with God, then something else had to be shared with us that was universal enough to be clear to every generation that followed; and at the same specific enough that it could be plainly lived out. Hence Christianity required a new Halakah– a new way of walking with the Lord. This ‘Way’ (Acts 9:2; 24:14) could not just be intellectual in nature- it could not just be ideas about God to stimulate our thoughts; it had to be a truth that would enliven our desire for God. It must enlighten our understanding but it also must quicken the will. In order for there to be a real friendship, what was handed down had to elicit a response from the whole person: his intellect and his will. And this is where we meet the second definition of tradition: it is a moral response to truth (Lessons V-VI). This is why the error of Gnosticism was, and still is to this day, such a threat to Christianity: it falsifies the notion that the Christian vocation is to truly love the Lord with the idea that we only need ‘understand’ Him by the light of our own special knowledge.

Third moment

The third way that we take the Tradition for granted is that we fail to appreciate the enormous riches that Christianity has contributed to and the profound effect it has had on human civilisation. The first and most fundamental of which was the creation of the concept of the human person, for it stands at the intellectual and cultural apex of Western Civilisation. We take the idea of the person as a given- whether that be divine persons, human person or even juridic persons. The idea of person is so utterly ubiquitous that it appears to us as just a natural category that has always been. We even wonder how a world could exist without it. Yet exist without it, it did.

The idea of the human person was not just an intellectual exercise worked out by a few men in a library who then published their thoughts to the world. It was worked out against the backdrop of doctrinal challenges, theological disputes, imperial persecutions and a clash with a pagan and hostile world. Christianity contains within it an obligation that the Old Covenant did not- it had to find a way of not just living in the world- it had to find a way to overcome the world (John 16:33). The Christian vocation was not to cooperate but to conquer (1Jn 5:4). But how does a religion based on the sacrifice of self (John 15:13) conquer the world? Christians were explicitly instructed that we were not to lord it over others (Mt 20:25-27), to not conquer by violence (Mt 26:52) or to ‘force’ conversions (Mt 16:24, Mk 8:34, and Lk 9:23). This was not only a new challenge to a new religion- there was no blueprint for how this was to be done- it also seemed like an impossible task. Yet the world seemed to understand, long before even the Christians themselves, that this new religion of a few marginalised Jews who worshipped a dead criminal would eventually overcome it. As the Lord Himself said: for the children of this world are in their generation wiser than the children of light (Luke 16:8). And this Christianity did not do by force, but by colonising the inner imaginary world of the person- It would speak new truths into his heart that would transform and renew his soul as he tasted and saw the goodness of the Lord (Psalm 34:8).

All of this ‘conquering’ would not take place so much in the outer world of men, but in the inner world of the man. This would not be achieved thorough politics, military might or legislation- even though Christianity would come to affect deeply all of those areas. Rather, Christianity would conquer not the ‘world’- but the world through the imaginary- the interior life of the human person. We would now no longer be conformed to this world, but to Christ (Rm 12:12). Our vocation was to become like Christ- which mean to have the mind of Christ (1Cor 2:16). Which is the third definition of the Tradition: to have the mind of Christ (lessons VI-VIII).

Fourth moment

The fourth way that we take the Tradition for granted is that we fail to understand the true nature of our redemption. On the one hand, through the merits of Christ crucified we have been raised to an order far beyond our original vocation- we now have the presence of God dwelling in our souls (1Cor 3:16) and we called to live as friends of God imbued with the Divine Life of God. Yet at the same time, we have been left with the temporal consequences of sin. Christ came to raise our nature He did not come to replace our nature. And so, in the meantime we are left with the reality of our frailty and our fragility. Or as St Paul so succinctly put it: we have treasure in earthen vessels (2 Cor 4:7). This predicament floods our consciousness from time to time, when we realise just how poorly we are living our Christian vocation. This temporal state of affairs means that a man must wrestle in his conscience so as to work out his own salvation in fear and trembling (Philippians 2:12). But this intensely inner struggle leaves a question very much unanswered: how does such an intensely intimate and personal religion relate to the world? The question with which the early Church has to answer was: does Christianity scale from the personal to the public? And if so, how?

When the persecutions against the Church ceased in the 4th century, Christians had to contemplate something for which they were more than likely not prepared- what do we do now that the world is not so openly against us- even though we do not dare to presume it is for us; for we cannot leave it as it is. And so, Christianity became a public facing religion, no longer being confined to the realm of personal piety and local charity. The colonisation of the inner world that had made Christianity legal in the Roman Empire, had to find some new expression in the material world around it. And at the same time, we had to be ever mindful of the Lord’s teaching: my kingdom is not of this world (Jn 18:36); all the while remembering that the world was still His creation.

How Christianity would scale from the personal into the public was by way of culture. Christianity that had been seen as a threat to the Empire, was actually not just a threat, but its replacement. Christianity spread not just by ideas, but ideas that became habits that formed institutions and shaped expectations. Christianity didn’t just become a religion tolerated in the Empire- it remade the Empire in its own image. But this it did universally by way of culture- not force. We did not just do a ‘Christian version’ of things- we made new things and we made all things new (Apoc 21:5). We made our own art, architecture, education, health care and philosophy. And perhaps the greatest of these new intuitions was the English Common Law. Which was not a project but a fruit- a fruit of a culture that had been imbued with the habits of Christ Himself. Culture became to the Tradition what the Church was to Christ- the tangible representation of a spiritual reality to a material world. The Tradition of the Church became a way of life because it taught us new habits and those habits created new institutions. The habits that it taught us were the habits of Christ Himself- according to His mind (Philippians 1:21). And this is where we met the fourth and final definition of Tradition: is the first habit of the Church (Lessons IX-XI). The Tradition of the Church is a principle of order in the Church and a principle that orders the Church- that is why it is the Church’s First Habit.

Culture and Tradition

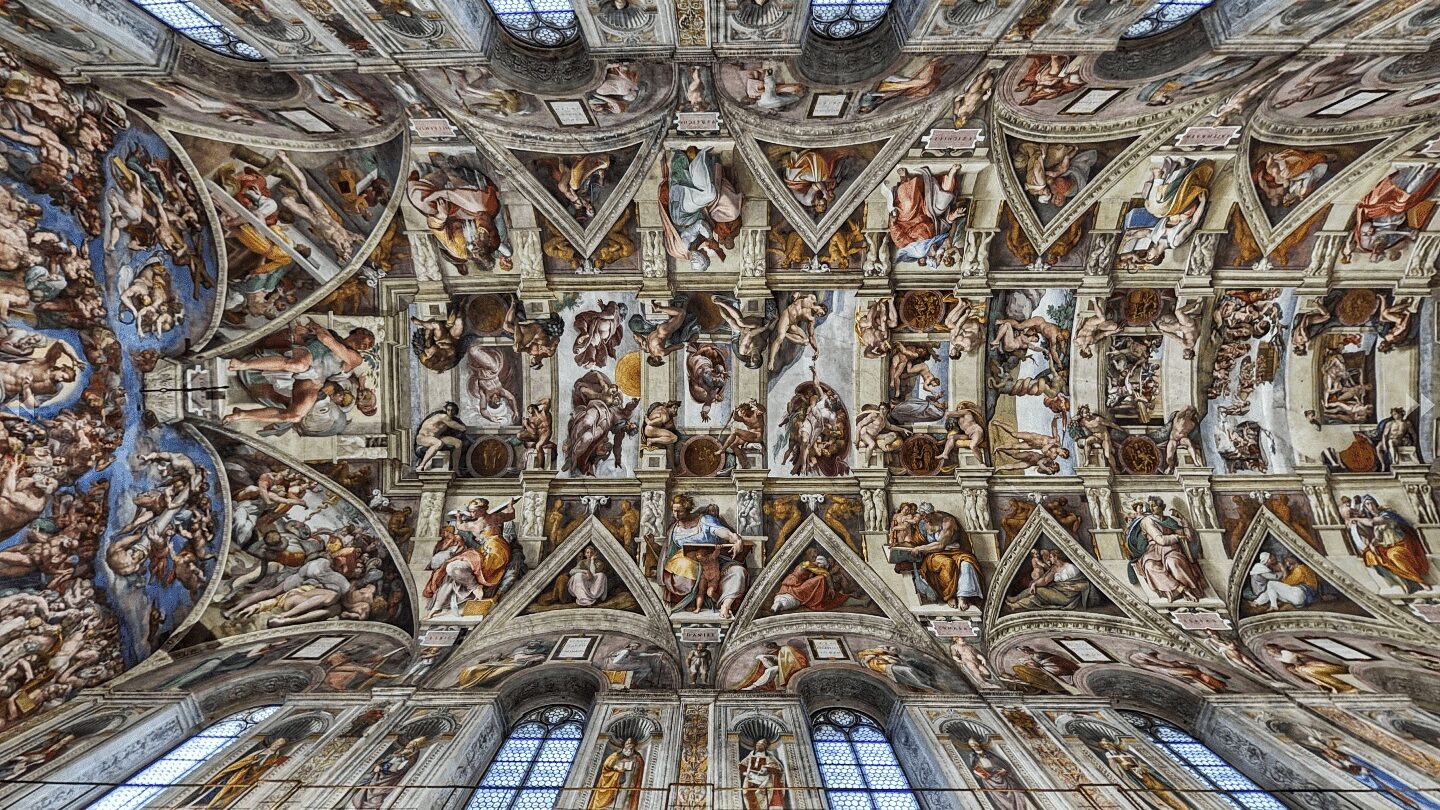

Tradition is not just a feature of Christianity- it is its structure. It is a principle of order not just of certain artefacts of our religion- doctrines or practices- it is the very nature of Christianity. The nature of Christianity is to be traditional. This is why tradition can be very hard to define and pin down because it cannot be separated from the very fabric of catholic doctrine and religion- because it is inseparable, it is thus harder to define. It is internal to the very structure of the catholic religion- part of its DNA. This is why it can be taken for granted and why it can therefore be ignored. And we have been ignoring it for the last several decades, and in the process, we are alienating ourselves from our true self. That is why culture becomes so important- both as a visible reminder of what the Tradition is, but also as a barometer to measure our fidelity to it. As the Church ceases to produce the great works of culture- art, architecture and learning- She ceases to live according to the wisdom She has received and the habits She has been taught. Catholic culture manifests Tradition to the world- but also reveals something of the inner state of the Church to Herself. Culture is a manifestation of the inner world of Catholic redemption- it captures the immaterial and makes it tangible to us. It gives body to the form of our religion.

Is there an answer?

And this is where we return to the title of this lesson: A Church of Lears. The challenge facing King Lear is the challenge of tradition- how does one hand on something precious to another generation? And how does one do this when the next generation is not prepared to receive it? I think this is a most succinct summation of the predicament facing modern Catholicism- how do we hand on the Tradition of the Church to a generation entirely ill-prepared to recieve it? If we have done anything over the last several decades, then it has been to denature the Christian religion form the Christian spirit. Instead of looking to our Traditions to answer our problems- we either look to the world or to protestant and evangelical programs in the hope they will right the ship- practices that alienate us form the very path that has brought us safely through the maelstrom of twenty centuries of human history. We look to solve problems with the products of error. They may look on the surface to promise us prosperity and success- much like the fruit of the tree of knowledge which promised us the same thing. And all of this is so, because we have been led by a generation unsure about the Tradition because it is unsure about itself. We are a church of Lears.

The problem of Lear is that he is no longer living according to the truth of something, rather he is performing it. Kingship is a vocation not a performance. As king, Lear wants to be the king and not be the king. He wants to enjoy his retirement by keeping all the benefits of office and assuming none of its responsibilities. This is not the way of kings. However, the tragedy of Lear is actually resolved, not in the story of Lear, but in the story of The Tempest, perhaps the last of Shakespeare’s plays.

The Tempest opens in the same moment that King Lear ends: in the midst of ferocious storm. King Lear ends in ruin because he discovers that the ‘natural man’- a man stripped bare of culture and civilisation- is actually something less than a best: he is a tragedy. The Tempest opens in the midst of another ferocious storm in which the efforts of a king (Alonso) to control it are shown to be as futile as they are in Lear. As the storm subsides, we discover that it was actually the result of Prospero- a magician who has the power to control the elements in the world of The Tempest. Shakespeare, after having shown us the futility of kings to control a storm and the tragedy of man in nature stripped of culture, creates a world in which a man can control the elements and cherishes culture. The Tempest is set in the world of the imagination of the artist- Shakespeare is allowing us to experience something of the inner world of the imaginary.

Prospero is in this world because he is the victim of a plot by his brother Antonio, who with the cooperation of Alonso the King of Naples, has usurped Prospero’s rightful claim to be the Duke of Milan. All of Prospero’s enemies have been washed up on the beach, carried to him by the storm. The question for Prospero is: what will he now do?

Prospero has a daughter, Miranda, who has fallen in love with Ferdinand, who has also washed up on the shore and who happens to be the son of the King of Naples, Prospero’s’ sworn enemy. The resolution that Shakespeare offers to this situation is perhaps the most Catholic of all his plays. The answer unfolds not as a series of demands in order to extract vengeance on his enemies, but rather as an inner transformation of those enemies through culture:

But if thou dost break her virgin knot before

All sanctimonious ceremonies may

With full and holy rite be ministered,

No sweet aspersion shall the heavens let fall

To make this contract grow, but barren hate,

Sour-eyed disdain, and discord shall bestrew

The union of your bed with weeds so loathly

That you shall hate it both.

Therefore take heed, As Hymen’s lamps shall light you.

Shakespeare, through the mouth of Prospero, is requiring these two young lovers to find their future and their way back into civilisation, not through a selfish obsession with each other, but by living according to the norms of culture: All sanctimonious ceremonies may with full and holy rite be ministered. A culture that has found its ultimate meaning and truest expression in the religion that created it. Shakespeare knows, like any good Catholic knows, that Christian culture is part of the Church’s remedy for our sinful nature.

Conclusion

You have perhaps noticed in this series that we have spoken about the Church’s Tradition without actually mentioning the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is only somewhat true. I am not a liturgist and I have no particular training in the liturgy. I am however a priest given over to the TLM- it is my panem quotidianum. I have not written about it explicitly because I know that there are people much more well instructed in it than I. I can only recommend them; I cannot add much to them. However, the one thing I would add at the end of this series is that as all of these various moments were unfolding in the Church, as we were deciding which were the books of Scripture and what was the nature of Christ; as we formulated the Common Law and did battle against the Gnostics, the one constant in all of this was the prayer that the Church prayed: the TLM. If you read everything we have written and you pray the TLM- you will discover yourself very close to these moments and the riches and treasures they hand to you.

The question we asked right at the very start of this series- does Tradition have a tradition- the answer is clearly yes. But the question was never as simple as yes or no. For if the answer is yes- what do we do now? And the answer to that question lies squarely in how the tradition of the Tradition unfolded in the life of the Church. And this is the heart of this series: that to follow the Tradition as it unfolded is to find a way back, not to the past, for that would be archelogy, but rather to find our way back to God’s eternal present. And this requires that we know something about what the Tradition has done, how it has done it and the culture that it has created. For we will not revive the Church until we have restored Her culture. And we will not rebuild Her culture until we have re-established Her Tradition. And the Church has shown us for the last twenty centuries exactly how to do that.

I hope you have both enjoyed and benefitted from this series. This may sound a little like self-promotion, but it is important that you read each lesson and in the order that it was written. Even if some of the lessons you know or if you find some parts of them a little difficult. They have been written at a level for any layman who has the desire to be well-formed. They are a measure of the level that you must be. This is not a requirement for salvation- the illiterate will enter the kingdom far more easily than I. They rather should be thought of as a measure of how you should put to good use the opportunities that have been given you (Luke 12:48). The way forward is the same way that has brought us to where we are: the Sacred Tradition of the Holy Catholic Church. And that Tradition must be everywhere and in everything that we do. It must be in the prayers we pray, the apostolate we embrace, the vocation we live and the culture we create. We have done our duty not when we have tended only to our needs, but when we have toiled enough so that we can say to the Lord: Abide with us: for it is toward evening, and the day is far spent.