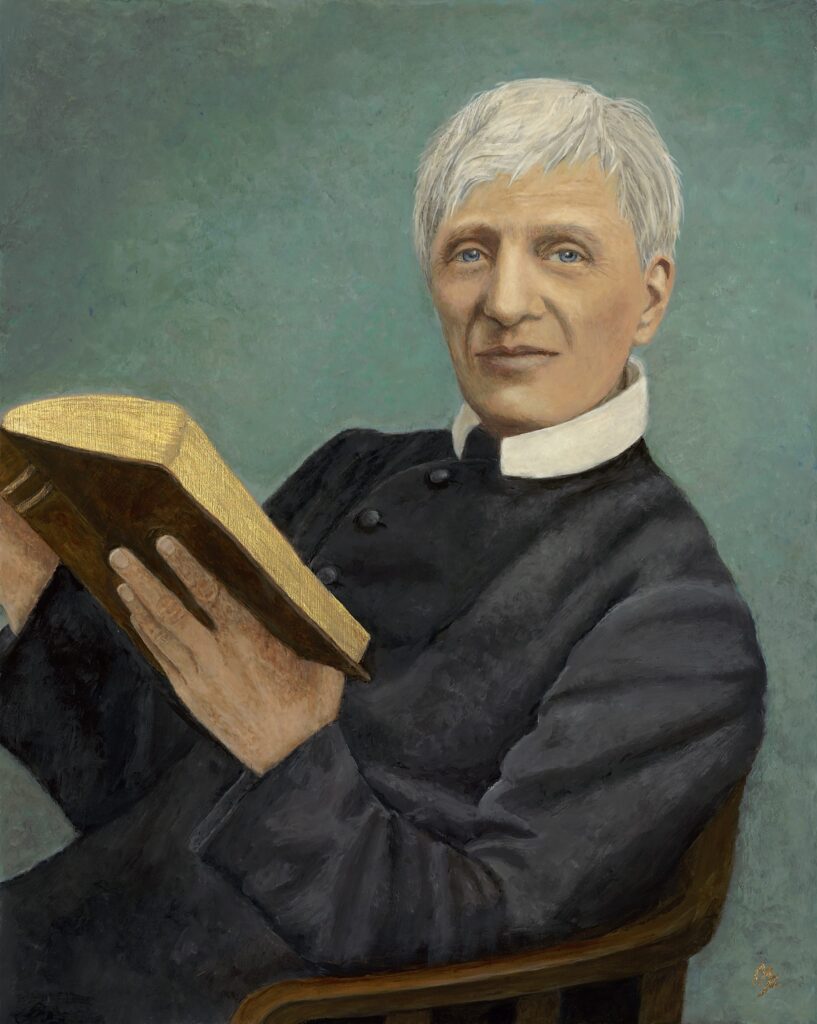

In this week’s article, we have a good friend Dr John Lamont writing about Cardinal Newman’s sanctity. Originally published in March of 2011, just before his canonisation, Dr Lamont’s article is as timely now as it was then. Cardinal Newman is to be made a Doctor of the Church. This article is an excellent reminder of what made Newman a saint in the first place.

Newman’s Sanctity

My topic is Newman’s sanctity; and by sanctity I mean those features of his life that can be presented as justifying his canonisation. The Church, in deciding whether or not to canonise an individual whose cause has been proposed, considers two factors. The first is the personal holiness of a candidate of his Anglican career, he was probably for canonisation: with the exception of those who die as martyrs, a saint must have exhibited heroic virtue, which guarantees that their souls are in Heaven rather than in purgatory or a worse place. The second is whether the candidate is a suitable object of devotion for the universal Church. Holy people who get to heaven number, we hope, in the millions. There would be no point in canonising them all, because canonisation means inaugurating a universal public devotion, and it is impossible to have universal public devotions to every member of the Church Triumphant. Blessed souls in heaven are chosen to be the objects of such devotion because of an exceptional degree of holiness that makes them unusually powerful as intercessors, or because their life in some way serves as a valuable model for all Christians in their pursuit of sanctity.

With respect to the first factor, there are a number of virtues that Newman possessed to a heroic degree. His personal life was marked by great asceticism, in fasting and abstinence from pleasures of the senses, in lengthy prayer that could last two hours a day, and in relentless hard work. Pope St. Pius X praised this last quality, in terms that are uncomfortable for a theologian to read: “Truly, there is something about such a large quantity of work and his long hours of labour lasting far into the night that seems foreign to the usual way of theologians.”[1] Newman’s asceticism was a true one because a cheerful one, untainted by humourlessness or gloom. At the height of his Anglican career, he was probably the most important and influential figure in the Church of England, which in those days meant that he of the most important people in Britain. He sacrificed this position when he converted to Catholicism, along with many friendships. He did not expect an important career in the Catholic Church; he was 45 at his conversion, an age that seemed closer to old age then than today, an age at which Napoleon had been forced to abdicate and retire to Elba in Newman’s youth. His low expectations were amply fulfilled. His efforts to use his talents in the service of the Church were frustrated by his enemies in high ecclesiastical positions, most notably by Cardinal Manning and by Mgr. George Talbot, Pope Pius IX’s private secretary. He lacked the duplicity needed in a successful ecclesiastical politician, and his objectives of improving the intellectual level of the Church and promoting the initiative of the laity did not meet with sympathy or understanding among his superiors – although we lament today that his farsighted plans were ignored. The heroism that Newman showed in his conversion was exercised throughout the rest of his Catholic life, in which he never stopped trying to do useful work in the face of discouragement and defeat – popping up like a jack-in-the-box, as one irreverent commentator put it, after every seeming failure.

There are two objections that have been made to Newman’s character. it has been claimed that he was hypersensitive, and that he was sharp and cutting towards those he disliked. It is certainly true that he was of a sensitive nature. This is not an obstacle to sanctity; sensitivity only becomes a moral flaw when it takes offence at innocent actions. It is admitted however that the people towards whom Newman was allegedly hypersensitive were ones who behaved in difficult, treacherous, or offensive ways. As for his sharp and cutting remarks, these were not made in the course of personal quarrels, but in public disputes where the good of souls was involved. These alleged flaws in fact have a useful lesson to teach about sanctity. Newman’s main life work was as a controversialist, opposing enemies of the faith and damaging trends in the Church. This line of work is a form of fighting, whose point is to win. It is wrong to win by immoral means, and Newman respected this, but even fair fighting is a form of fighting; and in fighting, you need to act in ways that will make people afraid of you if you are to win. Newman’s readiness to strike back against attack, and to use harsh words, meant that he was a bad man to cross. But this fact about him was a key to his achievement. If he had not been a bad man to cross, he could not have done the great work for God that he did; and this work is an essential part of what makes him a saint.

Opus vitae

We can admire the heroism of Newman’s life, but canonisation, as we have seen, is more than an endorsement of heroism: it teaches that the saint is an example for the universal Church. What was it about Newman that made him such an example? As with other saints, it is the work to which he devoted his life that must give the example. Newman described this work in the speech he made in Rome after being named a cardinal: ‘I rejoice to say, to one great mischief I have from the first opposed myself. For thirty, forty, fifty years I have resisted to the best of my powers the spirit of liberalism in religion. … Liberalism in religion is the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another.

This repeated his claim in the Apologia fourteen years earlier, where he said: ‘From the age of fifteen, dogma has been the fundamental principle of my religion: I know no other religion; I cannot enter into the idea of any other sort of religion; religion, as a mere sentiment, is to me a dream and a mockery.’ So Newman’s life work was being dogmatic about the Christian faith. This is the feature that is supposed to make him a pattern for all Catholics to imitate.

Many people will be surprised and repelled by this idea. Dogmatism is now thought of as a vice; it carries the connotations of being narrow, uncritical, judgmental, reactionary – in a word, dogmatic. How can this be a saintly virtue that all Christians should imitate? Was this not a shortcoming of Newman’s, which the Church should excuse rather than celebrate?

As often happens, a good way of understanding the truth about a question related to the faith is by answering the attacks of its enemies. An early attack that made use of Newman was that mounted by the modernists, many of whom claimed him as a support for their cause. George Tyrrell, the leading English modernist, describes Newman’s conception of theology as follows, in a letter to Wilfrid Ward: He puts theology on all fours with the natural sciences and its relation to its subject matter. It formulates certain subjective immanent impressions or ideas exactly analogous to sense impressions which are realities of experience by which notions and inferences can be criticised. In principle (with one or two unimportant modifications) this is Liberal theology?[2]

Ward, the influential author of the first standard biography of Newman, agreed with Tyrrell on this issue, and held that Newman’s thought was condemned by Pope St. Pius X’s encyclical Pascendi against the modernists. Ward wrote to the Duke of Norfolk: ‘I don’t believe the Pope meant to condemn Newman. But he has done so beyond all doubt so far as the words of the encyclical go – not only on development but on much else.’[3]

A related attack on the faith, one that seeks to discredit Newman rather than hijack him, is that mounted by Prof. Frank. M. Turner, the John Hay Whitney Professor of History at Yale University. In 2002, Turner published a book, John Henry Newman: The Challenge to Evangelical Religion, in which he argues that Newman’s claim to have devoted his life to upholding dogma was a falsehood, designed to curry favour with conservative Christians both Catholic and Protestant.

Turner asserts:

The most fundamental religious experience of Newman’s life was his adolescent conversion to evangelical religion. His reception into the Roman Catholic Church almost thirty years later represented the final step in what had been a long process of separation from that adolescent faith. That the conclusion of the process, which commenced in his mid-twenties, was Roman Catholicism, does not make it any more of a loss of evangelical faith than if, like others of his or later generations, he had ended in Unitarianism, like his brother Francis, or in agnosticism.[4]

We can pass over the surprising absurdity of claiming that changing from evangelicalism to Catholicism is really the same kind of thing as changing from evangelicalism to agnosticism, because it is not relevant to our subject.

The valuable aspect of Turner’s thesis lies in this: understanding why he is wrong about Newman having been converted to evangelicalism opens the door to understanding why Newman’s fidelity to dogma is a crucial virtue that is a model for the Church.

Doubt Rejected

The idea that Newman’s conversion was an evangelical one is disproved by the records he left at the time of his conversion in 1816, and in the years following. His initial temptation and sin was to intellectual doubt, and his conversion was a repentance and rejection of that doubt and sin; but rejection of intellectual doubt is intellectual belief. His private journals show no signs of evangelicalism, with his prayers focusing instead on the straightforward Christian request for the graces to resist sin and to grow in virtue. When in June 1821 he dreamt that an angel spoke to him, the topic of their conversation was not anything to do with evangelical religion, but the difficulty of understanding the doctrine of the Holy Trinity.[5] The book that most influenced him in his conversion, Thomas Scott’s The Force of Truth, was the story of a man ‘being led on from one thing to another, to embrace a system of doctrine, which hitherto he had despised’.[6] Scott’s conversion was from rejection to acceptance of the doctrines of the Trinity and the divinity of Christ. When Scott refers to ‘Methodism’ in his book, he makes clear that he understands it to mean Calvinism, which Newman initially accepted. The changes in belief that Newman underwent during his early career as an Anglican minister are more properly described as an abandonment of Calvinism, than as a rejection of evangelicalism. Newman’s description of faith is a dogmatic one, which does not bear any traces of evangelicalism:

What is faith? it is assenting to a doctrine as true, which we do not see, which we cannot prove, because God says it is true, who cannot lie…. he who believes that God is true, and that this is His word, which He has committed to man, has no doubt at all. He is as certain that the doctrine taught is true, as that God is true; and he is certain, because God is true, because God has spoken, not because he sees its truth or can prove its truth. That is, faith has two peculiarities;—it is most certain, decided, positive, immovable in its assent, and it gives this assent not because it sees with eye, or sees with the reason, but because it receives the tidings from one who comes from God.

…. We should religiously adhere to the form of words and the ordinances under which [Revealed Truth] comes to us, through which it is revealed to us, and apart from which the Revelation does not exist, there being nothing else given us by which to ascertain or enter into it.

Attacking the common mistake of supposing that there is a contrariety and antagonism between a dogmatic creed and vital religion’, he says: Knowledge must ever precede the exercise of the affections. We feel gratitude and love, we feel indignation and dislike, when we have the informations actually put before us which are to kindle those several emotions.

We love our parents, as our parents, when we know them to be our parents; we must know concerning God, before we can feel love, fear, hope, or trust towards Him. Devotion must have its objects; those objects, as being supernatural, when not represented to our senses by material symbols, must be set before the mind in propositions.

Tyrrell & Ward

Newman’s dogmatism can be better understood by contrasting it with Ward’s own view. Ward wrote:

[The High Church position] catches at, and is fascinated by, the gentle spirit of Catholic devotion, but shrinks from the iron walls and spiked palisades of anathema and definition, which are really necessary in the long run to preserve the life of devotion within from the inroads of free thought. …The world in one generation laughs at the Church’s senile superstition, in another reluctantly admires her strong organisation. Few look for her secret in the preservation of the primitive Christian ethos within that ugly wall of defence, made of bricks of different shapes and dates, the dogmatic theology.’[7]

The similarity between Ward’s account and Tyrells is obvious. An ethos, or an experience, or a devotion, and the dogmas of the faith are meant is the real heart of the Christian lite, to subserve it. Tyrell thought that the dogmas should be discarded when they are no longer adequate to experience (or example, some time before the anti-modernist encyclical Pascendi he had already decided that the Pope was an Antichrist and that Jesus had not intended to found a church), but Ward is more cagy about their dispensability.

For Newman, on the other hand, belief in dogma is not subordinate to the heart of the Christian life: it is the heart of the Christian life. We encounter God through understanding dogma, and we follow God through choosing to believe dogma. Everything else is subordinate to that.

It is obvious on philosophical grounds that Newman is right about dogmas being essential to religion; we cannot actually see or touch the supernatural, so our knowledge of it can only arise from the information that God gives us about it, which is what dogmas are. But this does not tell us why an insistence on dogma is spiritually valuable – why a dogmatic conversion should have made Newman a saint rather than merely a good thinker.

We can understand this by considering what it would have been like if Turner was right, and Newman’s first conversion had been to evangelicalism. Such a conversion would in the first place have been about Newman himself; it would have been Newman’s having an emotional conviction that ‘Christ loves me, Christ died for me’. Newman’s actual conversion, however, which we can call a dogmatic conversion, did not have Newman himself at centre stage; it was believing, against Voltaire and Hume, that Christian doctrine is true because God says so. Newman himself, of course, had a place in this conversion, but he was not the main actor in the drama. The great story of creation, redemption, and judgment that Christian dogma sets forth includes Newman among the countless throngs of the redeemed (if he repented) or the condemned (if he did not). His conversion was in the first place accepting this story as true, and then stepping forward to play his small part in it. The main human factor in the drama of Catholic dogma is not Newman, but the Church. That is why the Church was central to his faith and his life.

A similar point can be made about the modernist conception of Newman The modernists saw the basis of faith as a personal experience that was in some way deeply attractive. This puts the self and its gratification at the centre of religion. Newman not only denied that personal experience was the essence of faith; he denied that the dogma that was at the centre of faith was primarily concerned with the well-being of the believer. In Tract 73, he wrote:

“Mr. Erskine Thomas Erskine of Linlathen, a Scottish Episcopalian lay theologian], by a remarkable assumption, rules it, that doctrines are facts of the revealed divine governance, so that a doctrine is made the same as a divine action or work. … the Church Catholic has ever taught (as in her Creeds) that there are facts revealed to us, not of this world, not of time, but of eternity, and that absolutely and independently; not merely embodied and indirectly conveyed in a certain historical course, not subordinate to the display of the Divine Character, not revealed merely relatively to us, but primary objects of our faith, and essential in themselves, whatever dependence or influence they may have upon other doctrines, or upon the course of the Dispensation. In a word, it has taught the existence of Mysteries in religion, for such emphatically must truths ever be which are external to this world, and existing in eternity;—whereas this narrow-minded, jejune, officious, and presumptuous human system teaches nothing but a Manifestation …”

Turner is in fact half right when he says that Newman, as an Anglican, devoted his efforts to attacking evangelicalism. What he fails to acknowledge is that Newman did this because he saw evangelicalism as a form of liberalism. Because evangelicalism was centred on the self and the emotions, the dogmatic truth about God and the supernatural was not essential to it, and ended up dropping out of the picture. This is what happened to England in the 19th century; a country that in the early decades of the century was heavily evangelical had by the end of the century become largely unbelieving. It is what is happening in America today.

Newman’s dogmatism was thus a fundamental rejection of a religion based on the self. The difficulty of living by faith, living by the divine oracles that were the object of Tyrrell’s sneering hatred, rather than by experience or emotion, is in itself very great. It is made greater by the fact that after all we do not form most of our judgments through private, unaided experience. Our beliefs are shaped by, and largely taken from, what the people around us believe. The Catholic faith is thus confronted by a competitor, described by Newman in his last public writing, ‘The Development of Religious Error’ (1885):

“The World is that vast community impregnated by religious error which mocks and rivals the Church by claiming to be its own witness, and to be infallible… The World is a collection of individual men, and any one of them may hold and take on himself to profess unchristian doctrine, and do his best to propagate it; but few have the power for such a work, or the opportunity. It is by their union into one body, by the intercourse of man with man, and the consequent sympathy thence arising, that error spreads and becomes an authority. Its separate units which make up the body rely upon each other, and upon the whole, for the truth of their assertions; and thus assumptions and false reasonings are received without question as certain truths, on the credit of alternate appeals and mutual cheers and imprimaturs.”

In a sermon given to seminarians in 1873, he predicted the condition that the World is in today:

“I think that the trials which lie before us are such as would appal and make dizzy even such courageous hearts as St. Athanasius, St. Gregory I, or St. Gregory VII. And they would confess that dark as the prospect of their own day was to them severally, ours has a darkness different in kind from any that has been before it. The special peril of the time before us is the spread of that plague of infidelity, that the Apostles and our Lord Himself have predicted as the worst calamity of the last times of the Church. And at least a shadow, a typical image of the last times is coming over the world. … You will say that their theories have been in the world and are no new thing. No. Individuals have put them forth, but they have not been current and popular ideas. Christianity has never yet had experience of a world simply irreligious. … consider what the Roman and Greek world was when Christianity appeared. It was full of superstition, not of infidelity.There was much unbelief in all as regards their mythology, and in every educated man, as to eternal punishment. But there was no casting off the idea of religion, and of unseen powers who governed the world. But we are now coming to a time when the world does not acknowledge our first principles.”

Faith now involves not simply giving our assent and committing our lives to doctrines whose truth we take on faith, but doing so in the face of the vast moral pressure exerted by the World that surrounds us. This pressure is exerted in a negative form as scorn of belief in dogma and in a God who reveals it, and in a positive form as an endorsement of the worship of self that the modernists promoted, and that is the religion of our day. Newman’s lifelong commitment to dogma was a merciless war against these pressures, which had already become strong in his own time. That is what makes him a model for all Christians, and an especially important model for our time.

[1] St. Pius X, letter to Edward Thomas, Bishop of Limerick, in Acta Sanctae Sedis, vol. 41, 1908.

[2] George Tyrrell S.J., letter to Wilfrid Ward, 4 January 1904, in Letters from a ‘Modernist: The Letters of George Tyrrell to Wilfrid Ward 1893-1908, ed. Mary Jo Weaver (London: Sheed and Ward, 1981) p. 92.

[3] Letters from a ‘Modernist’, p. xxviii, quoting from Ward’s unpublished papers.

[4] Frank M. Turner, John Henry Newman: The Challenge to Evangelical Religion (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), p11.

[5] See John Henry Newman, Autobiographical Writings, ed. Henry Tristram (London: Sheed and Ward, 1956) pp. 151-153, 166.

[6] Thomas Scott, The Force of Truth (London, 1814), p. 122.

[7] Wilfrid Ward,’The Exclusive Church and the Zeitgeist’, in The Life and Times of Cardinal Wiseman (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1897), vol. II, pp. 561, 562. This epilogue to Wiseman’s biography was by Ward’s confession his own manifesto, and had nothing to do with Wiseman.