I say then, Has God cast away his people? God forbid.

For I also am an Israelite, of the descendants of Abraham,

of the tribe of Benjamin.

(Romans 11:1)

Introduction

At the time of publication, it is almost a month’s mind (trental) since the fatal bombing of a Catholic Church in Gaza. As many readers know, the story made headlines across the world and caused many secular news outlets and Catholic commentators to criticise the Israeli government and its defence forces (IDF) for those actions that led to the bombing. It is no hard thing to denounce the bombing of a church- Catholic or otherwise. But how should a Catholic approach the situation in the Holy Land?

When it comes to the practical side of war, the Church in recent times generally prefers to remain neutral as much as the situation allows. This can oftentimes look like ‘fence-sitting’ at the expense of justice. The Church however, maintains as much neutrality as possible in order to, if the situation permits, broker peace. It also allows the Church to condemn certain actions with much greater moral force, as she is seen to be denouncing a particular action rather than favouring a particular side. It also means she can work behind the scenes in order to make sure that humanitarian aid can reach those most affected. This she does with greater and less success; always knowing that in many conflicts, she will have believers on both sides. The practical effect is that there is no official ‘Catholic position’ on many conflicts. People of sound judgment must make the practical call, which is the role of well-formed lay Catholics and people of good will. Still, none of this helps us to decide what to think or do in the current situation.

In the present conflict in the Holy Land, according to the commentary, you are either pro-Zionism or pro-Hamas. You either support Israel- and thus all its claims; or you are an antisemite. You are either pro-Palestine or you are pro-ethnic cleansing. This kind of binary thinking is not very helpful because it does not exhaust all of the alternatives that are open to well informed and well-formed people of good conscience. This is not like cheering in a sporting match, where you have two sides and you must pick a winner. The situation is more complex and thus requires deeper analysis.

Holy See and Israel

Many Catholics don’t know that formal diplomatic relations between the Holy See and the State of Israel were established on 30 December 1993 after the adoption of a “Formal Agreement”[1] between the two states. A Vatican nunciature in Israel and an Israeli embassy in Rome were simultaneously opened on 19 January 1994. 1993 was a watershed moment in in the Holy See’s official relationship with Israel. So much so, that we can speak of pre-93 and post-93 approaches.

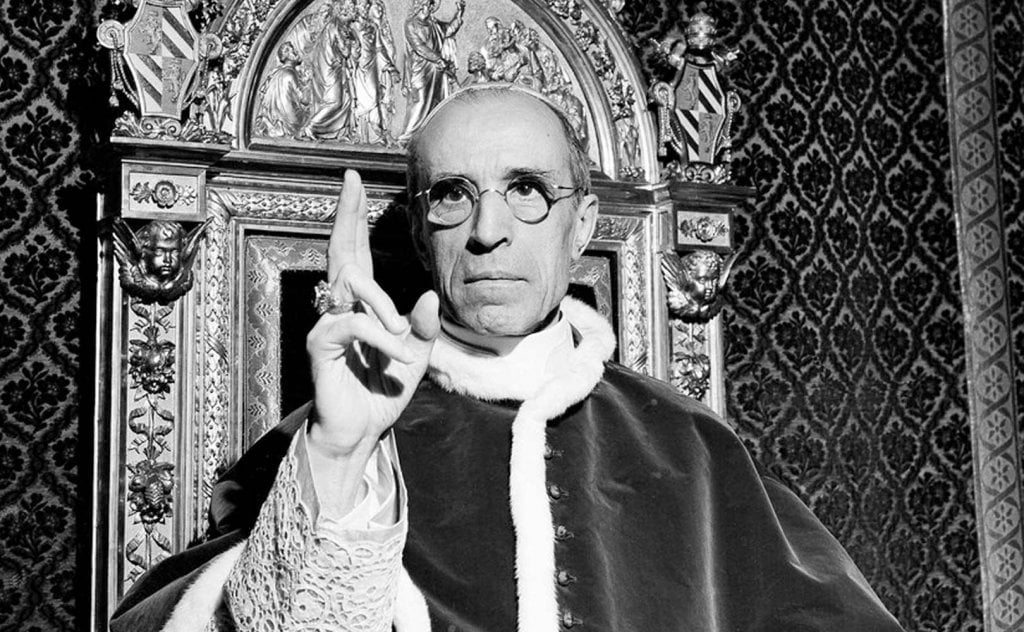

It can be argued that the papacy of Pius XII did the most in order to shape the pre-93 relationship between the Holy See and Israel. This is not to dismiss the many prior centuries of Catholic and Jewish history; but it is far too long and detailed to be given adequate attention in this article. Pius XII was Pope from 2 March 1939 until October 9, 1958. Much of the opposition to the creation of an Israeli homeland or state stemmed from the Church’s theological opposition to Zionism. Prior to Pius XII, both Pius X and Pope Benedict XV refused to support a Jewish State in the Holy Land. There is the well-known story that Zionist leader Theodor Herzi[2] in 1904, tried to obtain from Pope Pius X his support for the creation of a Jewish nation state, in which the Pope’s reply was: non possumus (we cannot).

Much of the Church’s attitude to the establishment of an Israeli state is informed by its theology and its pastoral concern. The Church has consistently rejected the theological claims of Zionism and has historically opposed it. Zionism considers the Land of Israel to be the God-given territory of the Jewish people as is evidenced by the entire Tanakh. It maintains that Zionism is an indispensable component of Judaism and thus a return to the land of Israel is a religious doctrine and practice of those in the Jewish diaspora. At the heart of this belief is the account of Abraham in the book of Genesis, who is selected by God to go into the land of Canaan with the promise that he would become the father of a great nation. This is Zionism’s biblical basis for a divinely ordained Jewish nationhood set aside for the Jewish people.

Zionism: Old and New Covenant

The Catholic Church rejects the premise that the Jewish people have a divine right to possess sovereignty over the Holy Land. According to St. Thomas Aquinas, the Old Covenant had three components: ceremonial, civil and moral. He argues that both the civil and the ceremonial are no longer binding, whilst the moral law of the Ten Commandments still binds as it pertains to the moral life which is ordered to the good according to reason. Accordingly, the religious argument that the Holy Land of Israel belongs to the Jews is rejected in the light of the revelation of the New Testament. For example, the Letter to the Hebrews: In that he says, A new covenant, he has made the first old. Now that which decays and grows old is ready to vanish away (Hebrews 8:13).[3]

As a pre-93 starting point to the Church’s understanding, there can be no better place to begin than Mystici Corporis Christi, the papal encyclical of Pius XII issued in 1943. The relevant section is usually quoted as:

Et primo quidem Redemptoris morte, Legi Veteri abolitae Novum Testamentum successit ; tunc Lex Christi una cum suis mysteriis, legibus, institutis, ac sacris ritibus pro universo terrarum orbe sancita est Iesu Christi sanguine. Nam, dum Divinus Servator in angusto territorio concionabatur — non enim erat missus nisi ad oves quae perierant domus Israel (cfr. Matth. 15, 24) — simul currebant Lex et Evangelium (cfr. S. Thom. 1ª 2ae q. 103 a. 3 ad 2); in suae autem mortis patibulo Iesus Legem cum decretis suis evacuavit (cfr. Eph. 2, 15), chirographum Antiqui Testamenti Cruci affixit (cfr. Col. 2, 14), in sanguine suo, pro universo humano genere profuso, Novum Testamentum constituens (cfr. Matth. 26, 28 et I Cor. 11, 25).[4]

This teaching is often referred to as supersessionism. Although this word does not appear in any formal teaching document of the Church and neither is it the term used in order to describe the Church’s teaching. This leaves us with a rather difficult position, that since the Church has never defined the term, nor used it to describe her position, it can be used by different people and in different ways. Since the Church has not used the word, neither will I in this essay. Rather, what I will do is to help you to inform your own mind in the light of what the Church has traditionally taught.

The Church has continually taught from the time of the writing of the New Testament and all through her fathers, that the New Covenant has taken the place of the Old and thus has abolished it. The abolition of the Old Covenant is not its repudiation, rather it is the recognition that it possesses no salvific merit in the light of the New. God has not renounced His original covenant- he has fulfilled it in the death of His Son. This has profound importance for the apostolic and missionary work of Christians amongst the Jews. That they too are called to be a part of the New Covenant and thus have a right to hear its preaching. Just as the Lord preached the Gospel firstly to the Jews, the Church must also do the same. As Cardinal Avery Dulles so succinctly put it: “if Christ is the redeemer of the world, every tongue should confess him.”[5]

Where to now?

All of this is just a smattering of the issues regarding the Jews and their claims to the Holy Land. The practical reality of course is much different. There does exist a State of Israel, that even though Catholicism does not recognise its religious claim, the Church does recognise its claims in law and thus its right to peace and its right to defend itself. However, this alone does not give us much of an idea about what to do and think in the present situation. And this is where the Church’s pastoral concern must also be considered. Firstly, her concern for the Christian people living in the Holy Land, and secondly for all of the holy sites that mean so much to Christians. Let me offer just a few thoughts.

Firstly, the Church’s position on Israel has changed throughout the course of history, not in a doctrinal or religious way, but rather in a practical way. From the non possumus of Pius X to the words of Pope Leo asking for the freedom of the hostages taken during the October 7 massacre, there has been a change in the practical judgement of the Church. This is part of the Church’s wisdom and Her ability to keep Her doctrines and at the same time express them in different historical circumstances. When one is being railroaded into the pro-Israel or pro-Hamas positions, it is important to remember that the issue is not always doctrinal, rather it is also practical. This has implications for how we must consider the issue and respond.

A practical consideration

Oftentimes in life, it is your friend who corrects you when you go wrong. Indeed, it is generally the case that your best friend is the only person who has the courage to correct you when you go most wrong. The fact that someone disagrees with your actions, is not a repudiation of who you are or your right to exist. The whole model of binary for and against does an injustice to the role that fraternal correction must play, even in international and diplomatic relations. There are some commentators who won’t hear any criticism of Israel- and they do a great injustice to that state, for wherever there is human action there is going to be human error. There are others who are hellbent on condemning Israel and who refuse to acknowledge the October 7 massacre in any meaningful way and the fact that there are still some hostages who have not been released- dead or alive. And that Israel has a right to defend itself against a terrorist organisation which wants to destroy it. Even though its self-defence cannot be achieved at any cost. In war, just as in life, more than one thing can be true. But when you are forced to pick a side, then necessarily, only one thing can be true for you. In the present situation both atrocity and injustice can be true. We just don’t always know. And that is the immediate problem.

When it comes to the suffering in Gaza, and the reports of starvation; it is not hard to imagine that in times of war there would be much misery. The issue of course is: who is at fault? The great difficulty we have is our lack of confidence in our media. We have all known those stories that were denounced as conspiracy theories and crackpot ideas, that turned out to be true. We also know that many actual stories were summarily ignored or even treated with contempt. Such is the bias that ordinary people have seen in media outlets across the world. So, when it comes to the question of what do we believe about events in Gaza the first question we have to answer is: whom do we believe? We will not know the entire truth of what is happening until after the war has long since stopped. But this does not help us either understand or act in the meantime. That is cold comfort to the suffering. However, the immediate concern must be to put pressure on Hamas, Israel and the UN to make sure that whatever suffering is happening- they end it. This is part of the reason for the Church’s perceived neutrality: there must be moral pressure placed on the shoulders of those with the responsibility and the capacity to act.

This leads us to consider where we started this essay: the bombing of the Catholic church in Gaza. This is an issue that has not been adequately addressed. It does appear that the mistaken bombing of the Church is unlikely, although in the heat of war, not impossible. This is not to make a conclusion about the issue, rather it is to highlight that we still need an answer. At present we only have an apology- but no explanation. Its delay due to circumstances of war, can only last so long. The delay must not become an excuse to deflect. Alas, the lack of follow up in the media, asides form political point scoring, is both predictable and disappointing. We need to know what happened, and a quick mea culpa without an explanation is not acceptable. Again, this may not be immediate, but it must be something that we continue to demand. Even when the conflict ceases.

Conclusion

Perhaps the most immediate and important thing that a Catholic can do now, is to insist that the pro-terrorism/ antisemite binary model is rejected. When asked if you are ‘pro’ the free and democratic state of Israel or against; or if you are ‘pro’ the poor suffering state of Palestine or against, the best thing to say is- “well, that depends on how they behave.” What matters is not just where I stand in theory, but how they act in practice. I am ‘pro’ wherever the true and the good are to be found; but against senseless aggression and acts of violence no matter who commits them. I do not believe that the present mess can be parsed in terms of sides, but rather actions. That may make me unpopular- but I think it permits the best opportunity to choose what is right.

[1] On 30 December 1993, the Holy See and Israel signed two agreements—the Fundamental Agreement Between the Holy See and the State of Israel and an Additional Protocol. The Fundamental Agreement is seen as a concordat that deals with tax exemptions and property rights of the Catholic Church and related entities within Israeli territory that entered into force on 10 March 1994, but has not been ratified by the Knesset.

[2] Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the Zionist Organization and promoted Jewish immigration to Palestine in an effort to form a Jewish state.

[3] There is much more to the New Testament understanding of the Jewish Covenant. But it is far beyond the scope of this essay.

[4] By the death of our Redeemer, the New Testament took the place of the Old Law which had been abolished; then the Law of Christ together with its mysteries, enactments, institutions, and sacred rites was ratified for the whole world in the blood of Jesus Christ. […] [O]n the gibbet of His death Jesus made void the Law with its decrees and fastened the handwriting of the Old Testament to the Cross, establishing the New Testament in His blood shed for the whole human race.

[5] Dulles, Avery (2002). “Covenant and Mission”. America. pp. 8–11.

One Response

Dear Fr Solomon

Thank you for this thoughtful essay. The Biblical basis for Israel’s claim to the Holy Land is contested, the Vatican has not acknowledged it, and if I recall Benedict XVI steered clear in his Communio essay a few years ago. It is of course a different question to the survival of the covenant. That said, there are many strong references in Genesis and Exodus to the “everlasting possession” of the land, eg Genesis 17: 8 (RSC CE 2nd). It is more explicit than Abraham’s being the father of a great nation.

Michael Gray