During the twelve years of the recently concluded pontificate, one of the most frequently heard pleas from Catholics around the world was for clarity to be given in both doctrinal and disciplinary matters. The longed-for clarity never came. As a new pontiff takes on the role of guiding the Church, it is time to ask ourselves some very pertinent questions, the first of which is this: was the widespread confusion of the Francis pontificate due to the man who then occupied the throne of Peter, or did it come from elsewhere? To read certain authors, one gets the impression that until Francis appeared, all had been fine; for many, all the problems began with him.

In Step… with a Wayward World.

In reality, Francis did not start the confusion; he only brought it to its apex by allowing the bitter seeds of confusion and error that had been sown decades earlier to come to fruition and bear their bitter fruit. To begin to understand how Francis became possible, one must go back and attentively consider what happened to the Catholic Church during and after the Second Vatican Council. When Vatican II opened its assizes, the Church was thriving around the world. Seminaries and religious houses were bursting at the seams. They literally did not know where to put the new candidates. Witness to this are many still extant buildings constructed in the late fifties and early sixties to accommodate the streams of young men and women flocking to the seminaries and cloisters, most of which have now been sold or converted into retreat centres. In those days, the practice of the faith was high; the divorce rate was low, Catholic families were large, onanism and abortion were rare, and sodomy was hardly ever mentioned except in a hushed, shamed whisper. The opening ceremony of Vatican II looked like a gigantic celebration of victory: the Church proudly showcased herself to the world in all her splendour. Few, very few, expected what followed.

While most of the Council Fathers came to Rome with the intention of proclaiming the eternal faith of the Church and giving ever greater incentive to her missionary outreach, things played out quite differently. The texts meticulously prepared by the preparatory commissions were rejected en masse, and substitutes were concocted over the next three years. What did these texts say? Much of what the Church had always said, but using new vocabulary that gave the impression something was being said other than what the letter expressed, and allowing for all sorts of adaptations and changes that would get the Church in step with the modern world. It was the famous aggiornamento, a term coined by John XXIII and loosely translated as ‘updating’. These new texts, precisely because of their mixture of Tradition and modernity, played a vital role in generating the confusion.

While this diagnosis may sound extreme to some, it does not appear that it is open to debate. While every ecumenical council has generated lively commentary, this was typically limited to theological perspectives that explained the doctrine of the faith with as much clarity and lucidity as possible. The aftermath of Vatican II was entirely different. Some may object that this was only because of the greater influence of the media in our day, and this is true to an extent. It was a favourite idea of Benedict XVI that there was the ‘real Council’ and then the ‘Council of the media’, that is to say, the way the Council was portrayed to the world by the press. For Benedict, as for John Paul II, the Council was guided by the Holy Spirit, and the media just messed everything up. However, if there were not already serious ambiguities in the Council texts itself, the media would have had nothing to play with. Go and read the texts of Vatican I or Trent and try to imagine the media having a field day with them, making them out to say the opposite of what the Church actually teaches. Hardly an option.

The confusion then lies squarely in the conciliar texts themselves, and it is totally unrealistic to hope for clarity in the Church today if we do not acknowledge this and fix it. But that would not be enough. Even if, by some miracle, we were to have a ‘syllabus correcting Vatican II’ from the Holy See, we would still need to go further back and look at the sources of the confusion that made possible the muddled minds of the bishops who wrote and approved the conciliar texts and that used them to dismantle the faith over the past sixty years. This will take us to the Modernist crisis and well beyond, and it will require several instalments. For today, we will limit ourselves to just one aspect of the confusion that came from the Council’s directives for liturgical renewal.

Pope Paul Leads the Way

If there is one area of Church life that immediately felt the shockwaves of confusion, it was the liturgy. Indeed, most Catholics never read the Conciliar documents; all they knew about the Council was what they saw and heard at Mass. And here, they soon found themselves in what can only be described as doctrinal and liturgical quicksand. Catholics had been accustomed to a way of worshipping God by attending Holy Mass, which they were told went back to the apostles, had never changed and never would. All of a sudden, they found themselves with an evolving liturgy, with new changes being introduced almost from one Sunday to the next. It would be fastidious to go into all the details. This has been done by expert and well-known liturgists.

For our purposes, it will suffice to dwell upon one aspect of the liturgical upheaval after Vatican II that has left its mark upon all that followed and that created, by its very nature, a confusion that is far from abating. The first document the Council promulgated was the constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium. The constitution nowhere mandated, nor even mentioned, turning the altars around to facilitate the celebration of the Mass facing the people. For sure, the idea had been in the air. ‘Experiments’ had been made for years in certain parts of the world but were frowned upon by the Holy See. Pius XII was alarmed at the situation, and so in the encyclical Mediator Dei he actually reproved the desire to ‘restore to the altar its primitive form of a table’.[1]

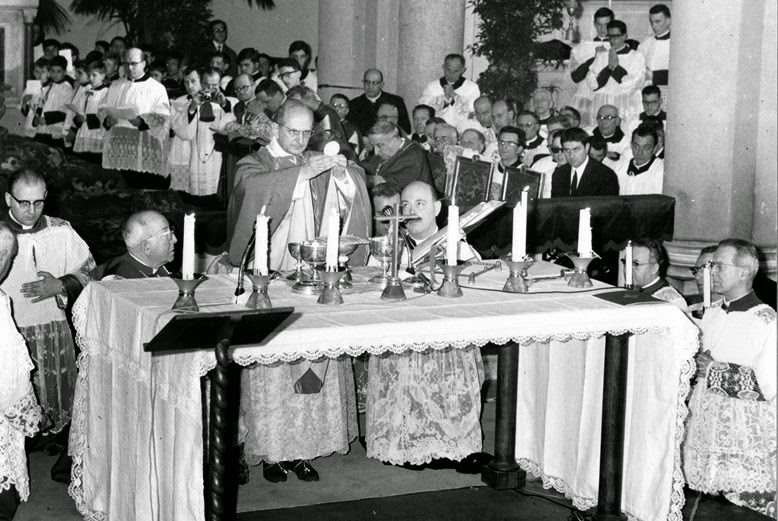

And then it happened. Paul VI himself led the way. In what can only be described as a seismic shift, this pope, of his own initiative and without the backing of the Council but nevertheless basing himself on the ‘spirit of the Council’, gave the liturgical revolution a giant kickstart by celebrating the first Mass ever in Italian and facing the people at the church of Ognissanti (All Saints) in Rome on 7 March 1965. Photos were taken of this historic event, in which one can perceive a makeshift altar set up for the occasion. The example set by the head of the Church meant that the practice was swiftly adopted everywhere. All of a sudden, in almost every Catholic sanctuary around the world, the Catholic faithful were confronted with something they had never seen before: the priest, whom they had been told always turned with them to offer on their behalf a sacrifice to God in atonement for their sins, now turned towards them, with his back against the tabernacle.[2]

Handed Down in a Mystery

Let’s take a moment to ponder what we are dealing with here. This is no purely anthropological question, though we will consider this perspective shortly. We are dealing with the highest aspect of Catholic worship, the most sacred act of our faith, the offering of the Divine Sacrifice of the Mass. And since the Mass was handed down to us by the apostles, we are talking about the sacredness of Tradition and its binding force. Is it coherent to imagine that Paul VI actually thought the entire Catholic people could undergo such a fundamental change in the orientation of worship without changing anything in the substance of that worship? Put another way, is it possible to imagine such a monumental change in practice would have no effect on the substance of the faith? Were the Catholic people so witless that they could be expected to accept that up till that one particular Sunday in the 1960s it was imperative for the priest to turn with the people to God in order to stress the sacrificial nature of the Mass, and that from that Sunday on, it was imperative to do the exact opposite, and yet continue to maintain that nothing had changed?[3]

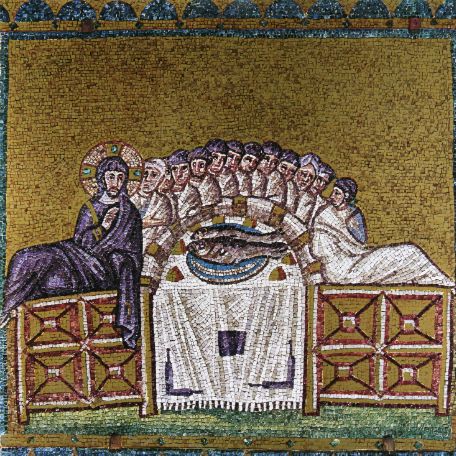

One of the main reasons put forward by the liturgical reformers was that, supposedly, in the primitive Church, Mass was said facing the people. No proofs were given other than the suggestion that the Mass developed from the Last Supper, and since the Last Supper was a meal, the first Masses must have been during a meal. But that only begged the question. In our day and age, we tend to think of a meal as a number of people sitting around a table and facing each other. But this is not what happened at formal banquets in antiquity. In those days, the ones dining did not face each other, but rather reclined on couches in a semi-circular position around a ‘U’ shaped table with one end open so that the table-waiters could enter and distribute dishes. The host would sit at the left corner of the table, as can be seen in a famous 5th -century mosaic in Ravenna, considered to be the oldest depiction of the Last Supper. In other words, it is highly likely Jesus and the apostles were not facing each other at all at the Last Supper; they were all looking in the same direction.

Furthermore, we know from numerous witnesses of the patristic era that it was the practice, in both East and West, for the priest and people to turn together towards the East, the direction of the rising sun, symbol of Our Lord Jesus Christ who is the Sun of Justice in His glory, who left the earth on Ascension Thursday by rising in the East (as Psalm 67:34 tells us: He mounteth above the heaven of heavens, to the east), and who will return to us from the same direction (according to Acts 1:11: This Jesus who is taken up from you into heaven, shall so come, as you have seen Him going into heaven). Just as the Jews always turned towards the temple of Jerusalem and the Muslims would later always turn towards Mecca, so from the first generation we find Christians turning towards the East.

One of the greatest doctors of the East, St Basil the Great, refers to the practice of the orientation of liturgical worship in the context of his study of the apostolic traditions that have not been transcribed in Holy Scripture. He seeks to explain that all our beliefs are not derived from Holy Scripture, but that many things were handed down by word of mouth, as the apostle clearly taught: ‘Therefore, brethren, stand fast and hold the traditions which you have been taught of us, whether by word or by epistle’ (2 Th 2:15). And to the Corinthians he writes, ‘Now I praise you, brethren, that you remember me in all things, and keep the traditions as I have delivered them to you’ (1 Cor 11:2). He then goes on to explain why this is the case, and gives several examples:

‘Of the beliefs and practices whether generally accepted or publicly enjoined which are preserved in the Church, some we possess derived from written teaching; others we have received delivered to us ‘in a mystery’ by the tradition of the apostles; and both of these in relation to true religion have the same force. And these no one will gainsay—no one, at all events, who is even moderately versed in the institutions of the Church. For were we to attempt to reject such customs as have no written authority, on the ground that the importance they possess is small, we should unintentionally injure the Gospel in its very vitals; or, rather, should make our public definition a mere phrase and nothing more. For instance, to take the first and most general example, who is thence who has taught us in writing to sign with the sign of the cross those who have trusted in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ? What writing has taught us to turn to the East at the prayer? Which of the saints has left us in writing the words of the invocation at the displaying of the Bread of the Eucharist, and the chalice of blessing? For we are not, as is well known, content with what the apostle or the Gospel has recorded, but both in preface and conclusion we add other words as being of great importance to the validity of the ministry, and these we derive from unwritten teaching. Moreover, we bless the water of baptism and the oil of the chrism, and besides this the catechumen who is being baptised. On what written authority do we do this? Is not our authority silent and mystical tradition? Nay, by what written word is the anointing of oil itself taught? And whence comes the custom of baptising thrice? And as to the other customs of baptism, from what Scripture do we derive the renunciation of Satan and his angels? Does not this come from that unpublished and secret teaching which our fathers guarded in a silence out of the reach of curious meddling and inquisitive investigation? Well had they learned the lesson that the awful dignity of the mysteries is best preserved by silence. What the uninitiated are not even allowed to look at was hardly likely to be publicly paraded about in written documents’.[4]

Bound by Tradition

Fr. Uwe Michael Lang remarks that celebrating the Sacrifice of the Mass towards the East ‘was the virtually universal practice in the Latin Church until the most recent times and is part of the liturgical heritage in the Churches of the Byzantine, Syriac, Armenian, Coptic, and Ethiopian traditions. It is still the custom in most of the Eastern rites for priest and people to face the same direction in prayer, at least during the anaphora. That a few Eastern Catholic Churches, for example, the Maronite and the Syro-Malabar, have lately adopted the celebratio versus populum is owing to modern Latin influence and not in keeping with their authentic traditions.’[5]

If we are to believe the witness of St Basil about the customs in the East (we are) and if Fr Lang’s painstaking research, which others have corroborated, is correct and true (it is), then it is clear that the practice of celebrating Mass with both priest and people turned towards the same direction, the East, was a custom that can with certitude be traced back to the Apostles themselves. How else could it have become universal? Who can fail to see that something that was practiced everywhere, in both East and West, can only have its origins in an apostolic injunction? And who could deny that a custom established by the Apostles themselves is not optional for the fitting celebration of Christian worship?[6] If the apostles declared that this is the manner in which Mass to be offered, then no one, not even a successor of the same apostles, has a right to say anything different or to act in any way contrary. The same Tradition binds the apostolic hierarchy, and even more so than the simple faithful, for the simple reason that it is the hierarchs who must lead by example.

A consequence of this is that no priest needs any permission to celebrate ad orientem, and no bishop can forbid it. This being said, the priest who becomes conscious of the problems with the modern practice and wants to change it would be well advised to first of all lead his congregation by means of serious formation to a proper understanding of this apostolic gesture, so that when the change is made it will be truly beneficial and not become a casus belli. It remains that the efforts of some bishops to ban the traditional orientation of worship are, strictly speaking, null and void. They are a form of clerical abuse which should not be tolerated.

Losing Our Bearings

Now, let’s set aside for the moment all the polemics of the past sixty years and try as objectively as possible to imagine what such a change can possibly mean in itself and what its implications might be. Forms correspond to certain realities. Suppose something has been done in a particular way for a very, very long time, in such a way that we call it an immemorial custom, that is to say, a custom whose origins no one can identify, for they are lost in a very remote past. This very fact can only mean that this particular custom has become an integral part of what that people do together. It is part of its identity, inseparable from it. To change such a custom, especially when the change achieves the exact opposite of what the previous custom sought to convey, can only be the cause of monumental confusion in the thinking of those upon whom it is imposed.

Furthermore, gestures are like words. If you change words, this is because you want to change something in what you are saying. If you change words that have become ritual, it can only mean that your rite is now signifying something different. If you say the opposite of what was said before, it means you want to reverse the very notion that was handed down, and say, not just something different, but its very opposite. The same goes for gestures. For the priest to make an about-face, a 180º turn in his manner of saying Mass, whatever pastoral explanations might be given to justify it, can only be perceived by a normal person as, at the very least, a reversal of perspective (literally). What can it possibly mean? A number of options are possible. It could be that, until now, the priests have been fooling the people into thinking they need not be involved in the Mass; in this case, this would make all priests in former times veritable charlatans. It could mean that they themselves did not know what they were doing before; this would essentially make them fools. It could mean that those today do not know what they are doing, and this, well, – let’s not say… In any case, it would seem impossible, from a purely psychological and sociological perspective, to dismiss the change as one of little consequence. One thing is certain: it means something, and that something cannot possibly be the same thing as the former practice which it has sought to reverse. It cannot be, for it would violate the laws of logic and human habits.

Whatever pastoral considerations might have motivated the reversal of the altars, it was the first time in the history of the Church that Mass was offered with the priest facing the people instead of facing God. Of its nature, this change was one of the first and gravest causes of the confusion in the faith, for, from a purely natural perspective, a 180º about face simply cannot go without consequences. Celebrating towards the East is not a practice that gradually developed over time and would therefore be expendable. Rather, assuming one’s intention is to offer to God a worthy sacrifice in the tradition of the apostles, it is an obligation in all Catholic rites. In the same way, we must also deduce – and this does seem inevitable, if what we have already said is correct – that a priest’s refusal to adopt the traditional posture ad orientem, and the adamant attachment to a celebration facing the people as if it were the only proper way to offer Mass, can only raise questions as to what such a priest really believes concerning the sacrifice of the Mass.

Conclusion

We began by stating that there are many causes of confusion that did not begin with Pope Francis. The position of the altar and the direction of celebration of the Mass is certainly one of them. We can now affirm that until the altars recover their proper position and the priest stands with the people towards the Lord, who is symbolised by the rising sun, there can be no hope for clarity, and confusion will continue to wreak havoc. The Christian people will continue to be afflicted with what we can only identify as a form of cognitive dissonance, stemming directly from the divide created in their minds and hearts by the innate longing of the Christian soul for Christ, the centre and focus of our prayer, while at the same time being forced to look at each other instead of at Christ. Lex orandi, lex credendi. If we observe the apostolic form of worship, we will have the apostolic faith, and our hearts will find rest. If we persist in not observing the norms of the apostles, our faith will always be wanting. It will remain confused, both for ourselves and for the world, and this is not a good situation to be in, for, as is well known, the Devil fishes in murky waters.

[1] Pius XII, Encyclical Mediator Dei, 20 November 1947, # 62.

[2] When considering this phenomenon it is hard not to be disturbed by these words of the prophet Jeremiah: ‘They have turned their backs to me, and not their faces’ (Jer 32:33).

[3] This seems to be what Benedict XVI was getting at when he wrote in the letter accompanying his motu proprio Summorum pontificum (7 July 2007): ‘What earlier generations held as sacred, remains sacred and great for us too, and it cannot be all of a sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful’. And yet, this is precisely what happened. To all intents and purposes it was forbidden for the priest to turn his back to the people while offering Mass, and regularly we hear of yet another bishop who has officially attempted to ban it in his diocese. We say ‘attempted’ because, as we shall see later, he has no authority to do so.

[4] St Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit, 27:66, in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Vol. VIII (The Christian Literature Company, 1895), pp. 41-32. Emphasis added.

[5] Fr. Uwe Michael Lang, Turning Towards the Lord: Orientation in Liturgical Prayer (Ignatius Press, 2004) p. 98.

[6] Let it be made clear that we are not talking about a valid celebration of the Mass. No one doubts the validity of Mass said facing the people, assuming the celebrant does indeed have the intention of doing what the Church does in offering the Mass. However, validity is not the only consideration when it comes to the public worship of the true religion. In it, every aspect and every detail is important because of the infinite dignity of the One to Whom we offer our homage. St Basil makes this clear in the text already cited.